“It is difficult to become a bird but it is relatively easy to become a boat: once you have a harbour you can drift far away from it.” — Geoff Dyer, Out of Sheer Rage

Geoff Dyer is very particular about the word “engulfed.” In a footnote to Another Great Day at Sea, his new book about two weeks he spent aboard the American aircraft carrier USS George H.W. Bush, Dyer quibbles with the narration of a video he watches in the ship’s museum about Bush’s experience as a navy pilot during World War II:

On one occasion [Bush’s] aircraft was hit on a bombing raid and was immediately ‘engulfed in flames.’ He continued on to the target, dropped his bombs on the target, and continued flying. By this time, the commentary explained, the flames were really bad (suggesting, at the risk of being slightly pedantic, that the plane had not been totally engulfed before).

When I first read this passage I barely noticed it; it seemed like a less successful instance of a technique that frequently makes Dyer one of the greatest living stylists of English prose, namely his eagerness to steer a paragraph sharply off course to pick up an observation that looks tiny but turns out to be momentous. I thought of it again when I reread “The Zone,” one of the pieces in Dyer’s superb collection of travel essays Yoga for People Who Can’t Be Bothered to Do It. Recounting his visit to the Burning Man festival in Nevada and its central, titular event, Dyer writes:

A comet or meteor shower passed a couple of hundred feet overhead and the Man started to burn. Suddenly everything was a Hindenburg of flame and everyone went completely mad. Sarah said, “Would you say the Man was engulfed by flames?” and I felt the word “engulfed” had never been used quite so aptly. In fact, everywhere was engulfed by flames, and there were naked people everywhere, charging round the flames, and everything was suddenly engulfed by everything else, even the desert, which was engulfed by the overarching firmament, which was all-engulfing. It was like the end of the world except it was like the beginning of the world.

If Dyer guards the word “engulfing,” it’s because it is a key concept for him. Much is made of the range of Dyer’s subject matter, but like most of the best writers he is constantly drawn back to a small circle of obsessions: the title of the “The Zone” refers both to the site of the Burning Man Festival and to “the place where your most cherished desire will come true” in Tarkovsky’s film Stalker, which will eventually become the subject of Dyer’s book Zona; the new book notes the similarity between the meticulous cleanup procedures aboard the USS George H.W. Bush and those at Burning Man. Present throughout his work is a desire to be engulfed, to be subsumed totally in one subject, one task, one experience, perhaps in death, anything that will obliterate the ego and its awful demands for a paralyzing abundance of pleasures and choices. Opposed to this is a desire for the ego to persist, and to get everything it chooses, which will usually be more choices. (His novel Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi is perhaps the purest distillation of this dichotomy.) This opposition has made him one of the greatest writers currently at work in the English language. It has also led him to write, in Another Great Day at Sea, a very bad book.

Commissioned as part of something called the “Writers-in-Residence” series, Another Great Day at Sea recounts Dyer’s exchanges with various shipmates: ordnance experts, the chef, a psychiatrist, brig workers. All of these exchanges sound promising in theory but few of them turn out to be interesting. The prose is at times astonishingly slack. A woman is referred to as “no-nonsense,” a meaningless cliché that one can imagine Dyer railing against in better form. Paul, Dyer’s official minder, is described without irony as “a great guy, super-efficient at everything he did, always stepping up to the plate . . .” Phrases like “great guy” and “stepping up to the plate” belong in a hastily written email by an overly friendly manager, not in a book by Geoff Dyer. (The title comes from the captain’s own managerial speak; every day is supposed to be “another great day at sea.”)

The book’s central problem is that Dyer does not appear interested in the people he meets on the ship as people, but as corporeal representations of work ethic and purpose. I lost track of the references to “the fourteen-hour days” that the crewmates work, but I’m pretty sure there were somewhere around fourteen. These men and women have something important to do, and Dyer doesn’t want to let you to forget it, even though you don’t get to know any of the men or women very well at all. Are any of them annoyed by the captain’s enforced cheeriness? We don’t know. Is the chef, who dreamt of becoming the chef at the White House but found her application thwarted by bureaucracy, bitter? Dyer wonders for a moment, but quickly gets distracted. The closest we come to differentiation among these people is when one man is referred as “more in love — if such a thing were possible — than the other people I’d met who were seriously in love with what they did.”

Dyer suggested an aircraft carrier for his “residency,” he tells us, because of his childhood obsession with warplanes and because the military represents the “polar opposite” of his life now, his life as a writer. Whereas crewmembers are straight-laced, purposeful and self-denying, writers are desiccated, purposeless, and pleasure-seeking. (Writers are also lacking in basic manners: when a crewmember politely takes extra steps to ensure that Dyer does not catch a cold, Dyer notes that at “literary parties” he has been kissed by people who have afterward announced that they have colds. If there’s a way for writers to be terrible, they will find it.) The Navy offers little opportunity to shirk off a morning’s work, or to dither about where to live; in other words, it offers little opportunity to do the things that Dyer, in his masterwork Out of Sheer Rage, recounts doing instead of writing a biography of D.H. Lawrence. That book’s “real subject,” he writes at the end of it, has been despair: the despair of being without anchor, the despair of not knowing what to do, the despair of having too many choices. “And since the only way to avoid giving into despair and depression,” he writes, “is to do something, even something you hate, anything in fact, I force myself to keep bashing away at something, anything.” There is a desire for purpose so absorbing it is indistinguishable from oblivion, and there is no purpose more absorbing than war, which brings oblivion. War, in other words, is yoga for people who can’t be bothered to do it.

Even the best writers frequently write bad books, and it is usually prudent to pass over such failures in silence. Another Great Day at Sea is worth discussing because the need to “keep bashing away at something, anything” is behind much of America’s War on Terror, and is certainly behind the perplexingly timid response of most Anglo-American writers to it. 9/11 appeared to grant precisely the sort of great, clear purpose to a generation that had come of age in the late 1980s and early 1990s and felt besieged by too much choice and too little meaning, a stage of siege from which 9/11 seems to have felt to many writers like a reprieve. David Foster Wallace’s “The Suffering Channel,” the closing novella in his short story collection Oblivion, tells of the frivolous doings of a frivolous magazine in the World Trade Center in the summer of 2001; we understand that they are about to get what is coming to them for being frivolous.

Wallace is an important figure to consider next to Dyer; both polymaths, they both bring their vast learning to bear on questions of distraction, purpose, and annihilation. Another Great Day at Sea occasionally reads like an inversion of “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again,” Wallace’s masterly essay about a luxury cruise. Absent martial purpose, or any purpose at all, the cruise is a kind of hell that leaves its pleasure-smothered passengers in a state of misery akin to shellshock: “I have seen sucrose beaches and water a very bright blue. I have seen an all-red leisure suit with flared lapels. I have smelled what suntan lotion smells like smeared over 21,000 pounds of flesh.” This ship is marked by enforced idleness and can engulf only in a fiery boredom. When Wallace attempts to do something, something as simple as carry his own luggage, he nearly gets a crewmember fired, as crewmembers are not permitted to permit passengers to carry their own luggage. Stripped of responsibility, and under intense pressure to feel no stress, Wallace finds his soul in a very serious kind of danger. “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again” is much better than Another Great Day at Sea, if only because it is almost always more engaging and edifying to watch a writer diagnose a problem than attempt to solve it.

In another essay, Wallace floats a solution to the problem of too-abundant choice that is oddly similar to Dyer’s: to be engulfed in flames. “Back in New Fire,” published in 1996 in Might Magazine and included in the posthumous collection Both Flesh and Not, imagines AIDS as a dragon that threatens to incinerate his “knightly friends” as they pursue casual sex. In Wallace’s telling, contemporary sex faces no opposition, and is therefore without purpose. You see, before the 1960s, various dragons — religious and cultural proscriptions such as “the automatic ruin of ‘fallen’ women” — made sex a “deadly serious business,” whereas after the 1960s sex became too easy to acquire. A mere handful of pages, the essay may be the most morally repugnant work ever written by a major American writer who is not Ezra Pound. Let me flick a few of its embers your way:

If I’ve got some of this right, the casual knights of my own bland generation might well come to regard AIDS as a blessing, a gift perhaps bestowed by nature to restore some critical balance, or maybe summoned unconsciously out of the collective erotic despair of the post-‘60s glut. Because the dragon is back, and clothed in a fire that can’t be ignored.

Again, this is David Foster Wallace, not Jerry fucking Falwell. With unintentional hilarity, the next paragraph begins “I mean no offense.” Something has to have gone catastrophically wrong in one’s thinking before one wonders whether AIDS is “a gift perhaps bestowed by nature to restore some critical balance,” a phrase that even many right-wing religious fundamentalists would likely consider beyond the pale. Something has to have gone catastrophically wrong in one’s thinking before one can ask whether a disease that has killed millions is “a blessing” because it might cure you and your (heterosexual and male, it seems) friends of “blandness.” Really, blandness isn’t that bad.

It is also important to remember that the appearance of a martial purpose, whether in the form of sex-knights doing battle with AIDS in order to “win” women, or in the form of a bunch of people stranded on a ship fighting a sort-of war with no foreseeable end against a poorly defined enemy. There is one exhilarating passage in Another Great Day at Sea when Dyer realizes that what has looked like purpose is in fact no such thing. Towards the end of the book, standing alone on the ship — rather than engaging in a superficial conversation with someone he wants to put on a pedestal for working hard — he suddenly breaks through the hull of bullshit he has spent the entire book constructing:

The monotony of life at sea is not confined to the jobs people do. Seeing the sun rise and set every day in the unchanging sky over the unchanging — and constantly changing — ocean is inherently meditative, and it was easy to fall into a cognitive trance out there on the fantail . . . In my case this fantail trance took the form of a kind of mental seasickness whereby the clarity and fixity of the carrier’s unquestioned purpose gave rise to feelings — and questions — of purposelessness.

Yes! Yes! There’s Geoff! Good to see you, buddy, we missed you. C’mon, keep it going:

Did the presence of these carrier-launched planes in the skies over Iraq accomplish anything at this moment in history (especially if one considered the actual and opportunity costs of doing so)? Wasn’t it in some ways an unbelievably expensive and noisy provocation? Weren’t the planes flying missions primarily because the boat was here and because that’s what planes do? This in turn raised other doubts about the constant guarding against risk and threat. The carrier would not have been at risk if it had not been there.

Here, brilliantly and concisely stated, is the contradiction that we, as fans of Dyer and as citizens of the country that has put this ship here, need Dyer to explore: the question of whether this purposefulness actually serves any purpose, or whether it is merely making everything worse. An idle mind may be the devil’s playground, but that doesn’t mean we should start doing the devil’s work. (“So do you suggest we do nothing?” the warmonger asks in every crisis.1)

Dyer continues to ask pertinent questions for another page or so, empathizing with the Iranians, wondering how we Anglo-Americans would like it if “the Eyeranians had a carrier twenty-eight miles off the coast of Maine or Cornwall.” Then these questions suddenly evaporate, totally forgotten for the rest of the book, perhaps because they demonstrate that Another Great Day at Sea, along with the American foreign policy it depicts, needed to be scrapped and then totally reconceived. Instead, Dyer remains engulfed in the Gulf.

Hearing of a suicide on another ship in which someone wrapped himself in chains and jumped off the flight deck into the ocean, Dyer writes that this is “so much more of a death, somehow, than Virginia Woolf stepping into the Ouse with a pocketful of stones.” More, somehow? How? Woolf, Wallace, and this servicemember suffered from varieties of depression and despair that led them to suicide; their deaths are equal and equally tragic. The very idea of one death being “more” than any other death strains toward a martial mentality that Dyer is simply too smart for.

The liveliest passages in this book are, tellingly, those that celebrate life, life in its grubby, silly, selfish glory. Dyer fights for a cabin of his own rather than a cabin to share with five other people, even though many of those onboard have to share a berth of sixty; Dyer delights when he is able to eat the food prepared for the captain rather than the food prepared for the crew. He is at his best as a writer when he stops genuflecting and starts enjoying himself. But he doesn’t allow this to persist for very long; after eating the captain’s food he starts to refer to himself in the third person, as “Beachbelly,” fat and lazy in comparison to the one-dimensionally vibrant crew. Similarly, Wallace writes in “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again”: “I am instated in Nadir cabin 1009 and eat almost a whole basket of free fruit and lie on a really nice bed and drum my fingers on my swollen tummy.” Indulgence of appetite is associated with lassitude, which is associated with the writers, in contrast to workers.

But writers are workers, or at least we can be. We can examine official language and expose its evasions; one thing that is so disappointing about this book is that, writing about an endless war that continues to produce appalling abuses of language, the only instance that Dyer can muster the energy to complain about is a trivial misusage of the word “engulfed.” Perhaps more importantly than our duty to language, but inextricable from it, is our duty to tell stories, not only our own stories but those of other people. But in order to tell anyone else’s story — or to tell our own in a way that will have relevance to others — we must have belief in our ability to do so. To avoid solipsism, we must have self-respect.

We often think that constraining freedom of the the kind that preoccupies Dyer and Wallace arose spontaneously in the 1960s, but the dynamic is very much on display in Saul Bellow’s 1944 debut novel, Dangling Man, about a man waiting to be called to serve in World War II. Supported by his wife, he has nothing to do except work on his essays about Enlightenment thinkers, but finds himself unable not only to write but to read anything other than the newspaper. He thinks about getting a job, but he is “unwilling to admit that I do not know how to use my freedom and have to embrace the flunkydom of a job because I have no resources — that is to say, no character.” The novel ends with the narrator finally being called to serve. He greets this happily, but the novel’s final lines are sardonic:

I am no longer to be held accountable for myself; I am grateful for that. I am, in other words, relieved of self-determination, freedom cancelled.

Hurray for regular hours!

And for the supervision of the spirit!

Long live regimentation!

Enrollment in the military solves the problem of how Bellow’s narrator is going to spend his days, but it doesn’t solve the deeper dilemma of what one is to do with oneself, or of how one is going to relate one’s country. He is being shipped off to fight The Good War, meaning the one with the dragon that all of us can agree needed to be killed at any cost, but once the dragon is killed he will be returned to himself. The supervision of the spirit is not the same thing as its fulfillment, or as its being put to good use.

At the end of Out of Sheer Rage, Dyer writes:

My greatest urge in life is to do nothing. It’s not even an absence of motivation, a lack, for I do have a strong urge: to do nothing. To down tools, to stop. Except I know that if I do that I will fall into despair, and I know that it is worth doing anything in one’s power to avoid depression because from there, from being depressed, it is only an imperceptible step to despair: the last refuge of the ego.

I don’t think I’ve ever read a paragraph I identify with more strongly, or a paragraph that I am more grateful was written. The urge to do nothing and the despair that results are difficult to admit, but I struggled against them as I wrote this essay, as I struggle against them whenever I write or do (or don’t write or don’t do) anything. It is possible that my days would be happier if I spent them swabbing the decks of a ship that was carrying planes that would carry death to an enemy I believed needed to be destroyed. But this is a daydream as idle as any of my other daydreams, and I have far more cause to be ashamed of it than I do of my urge to check Twitter. The desire to be engulfed in a great cause cannot be separated from the concomitant desire for a great cause to be engulfed in, whether it be a war or an epidemic. Far from being the solution to the desire to do nothing, the drive for purpose is another and far more dangerous enemy. It is this compulsion that led us as a culture to exaggerate the threat posed by Al Qaeda, to assume that the only possible response to the attacks of 9/11 was a generation-long war that would set an ever-expanding portion of the world aflame. It is possible to combat both pleasure-seeking laziness and death-tinged purposefulness, but it is important first to affirm that, if we have to choose between the two, laziness is a lot better than war.

__

1As this essay is being published, another crisis has arisen, and planes are being launched from the USS George H.W. Bush to conduct airstrikes against the Islamic State. Meanwhile, the New York Times writes of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, that group’s leader, that “at every turn, Mr. Baghdadi’s rise has been shaped by America’s involvement in Iraq.

David Burr Gerrard‘s work has appeared in The Awl, The LA Review of Books, The Millions, Specter, Extract(s), and elsewhere. He teaches creative writing at Manhattanville College. His debut novel, Short Century, has just been published by Rare Bird Books.

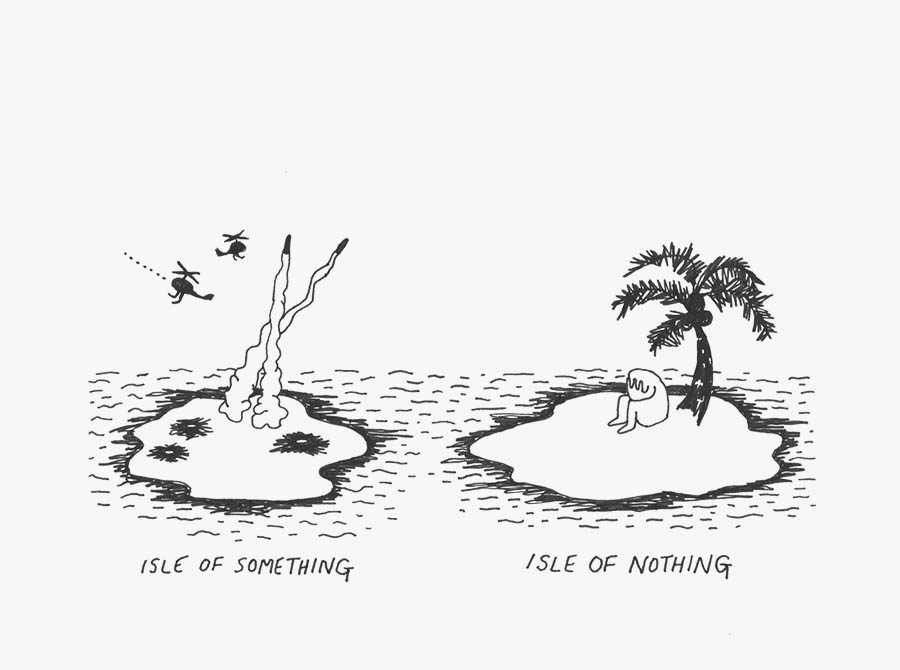

Illustrations by Eliza Koch. See more of Eliza’s work here.

This post may contain affiliate links.