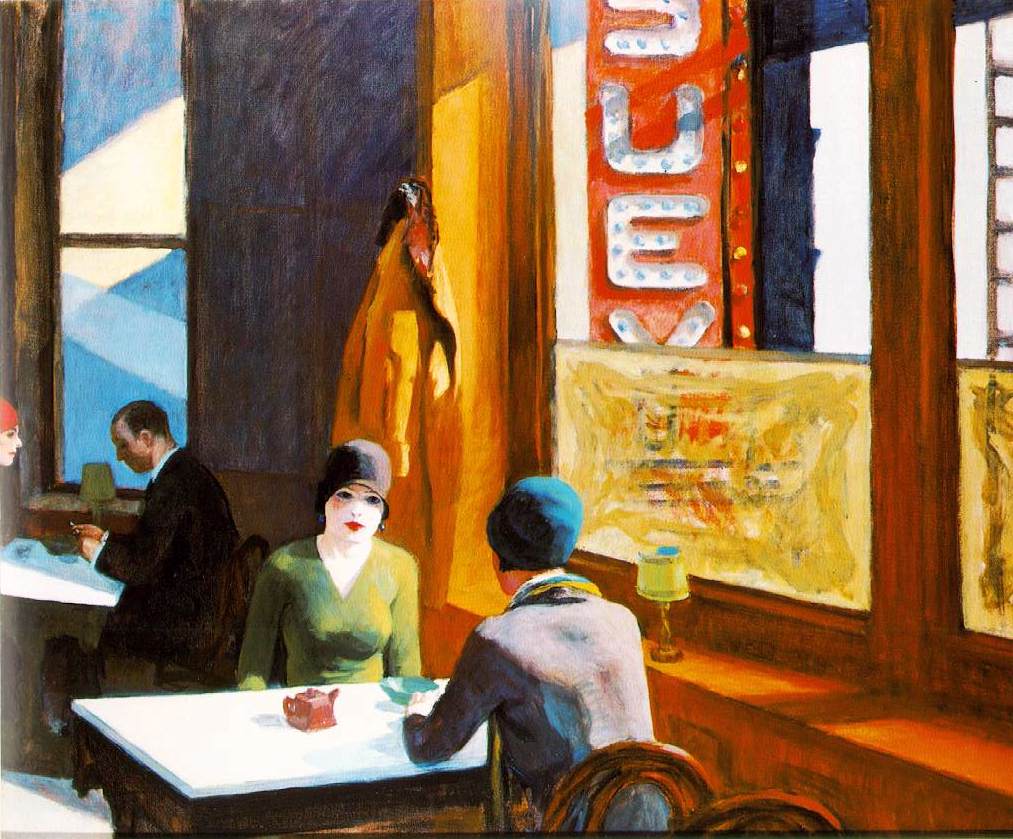

Via Wikiart.org.

There is a painting by Edward Hopper that expresses what, for me, is most beautiful about Chinese restaurants in America. Chop Suey (1929) is predictable: Ashcan realism, bobbed and cloched blondes, a sense of splendid isolation. Two women face each other across a table in a Chinese restaurant, a giant sign dangling in the right foreground: —SUEY. For Hopper, a chop suey lunch is an excuse to bringing these two Manhattanettes together and a totem that demands a ritual. If this painting is to be believed, there have always been Chinese restaurants of this sort that refract our experience of urban life into a moment of pure but conflicted desire. To look at this painting, to really gaze into it, following the cliché, to feast upon it, is to long for sensations we know are unpleasant. Loneliness, disgust, frustration. But once we believe the painting, accept its reality as true, we sacrifice our ability to deny what is illuminated and flashing or bolded on the wall. To ignore the artificial glamour of the artificial totem.

In The Secret Agent, Joseph Conrad describes a particular species of Italian restaurant in London at the turn of the twentieth century:

the patrons of the place had lost in the frequentation of fraudulent cookery all their national and private characteristics. And this was strange, since the Italian restaurant is such a peculiarly British institution. But these people were as denationalized as the dishes set before them with every circumstance of unstamped respectability . . . They seemed created for the Italian restaurant, unless the Italian restaurant had been perchance created for them.

In the case of the Chinese-American restaurant, the conjunction ought to be and, not unless: the patrons of Chop Suey had been created for the Chinese restaurant and the Chinese restaurant had been created for them. Restaurant and customers, like paint and image, are indivisible. An average Chinese restaurant, anonymous and representative, is therefore anything but banal. When you sit down and buy lunch, you enter into an extraordinary transaction. You exchange individuality and autonomy to become part of the interior, to experiment with the boundary between self and environment, habit and the bizarre. Thus total isolation in the company of others, or the exotic but pathetically unremarkable interior of Chop Suey. Even as the Chinese restaurant is incorporated into mainstreet culture, it opens an alternate world of social practice that encourages transgression. The effect is to expose the social processes that maintain the daily basis.

The first Chinese restaurant I remember was in a strip mall. It had an all-you-could-eat buffet with egg drop soup and fried rice. Calendar placemats. On the wall, a magnificent relief in bronze or plastic of running horses. My first encounter with Chinese culture, as an eight-year-old white Jewish kid from middle-America-somewhere who liked to eat as much lo mein as possible as quickly as possible to get to the little sausage shaped donuts rolled in granulated sugar before the one other family in the dining room, was American kitsch. Pre-packaged, mass-produced, like the restaurant concept. The pervasive similarity of Chinese restaurant menus and design can be traced to catalogue warehouses of Chinese menus and design elements that cater to immigrants opening restaurants in, say, Lexington or Detroit. Ten years later I would read Edward Said, learn about Orientalism, and think, oh, that’s what was going on. Hip restaurants in New York that boasted about American Oriental food would nauseate me. Indignation was not a productive response, though, alienating me from anyone other than the choir I might be preaching to and flattening out the difference between parody and uncritical applause. Could there be a way to think between criticism and celebration? To look at fried rice and a chintzy sculpture between avant-garde and kitsch?

Another way of asking those questions is to focus on how a Chinese restaurant models a certain set of social and aesthetic expectations, or to think about the Chinese restaurant not as a cultural form that demands criticism or celebration, but instead as a component in the spatial structure of American social life. Why then is the Chinese restaurant consistently a domain where transgressive behavior becomes threatening and comic, exceptional and routine, excessive and necessary? Because the Chinese restaurant is a fantastic site produced by simulation, it is a safe space for experiment.

In John Cheever’s (now forgotten) novel Falconer, a Chinese restaurant in Kansas City is the setting for a gay hustler to pick up johns, foreshadowing same-sex desire in the novel’s title location, a prison. “My thing with this man began in a Chinese restaurant,” the Cuckold tells Falconer’s protagonist, Farragut. The Cuckold often eats alone in the restaurant, he tells Farragut, never Chinese food, always a London broil or Boston baked beans, until the hustler makes his move. The restaurant moderates between vulnerability and exposure, yet disguises both in the turn from “Oriental” to ordinary. Rather than a truck stop or public restroom — other valid and perhaps more realistic settings for the hustle — the Chinese restaurant stages homoeroticism as predictable. It finds a place for loneliness and sex on the back of the menu.

Via Hollywoodreporter.com.

Likewise, the Chinese restaurant in David Mamet’s play Glengarry Glen Ross serves as an alternative to a different after work destination: the heterohome. Over bowls of Americanized Chinese food, friendship evolves into criminal conspiracy. Again, the solo diner finds companionship in another man, but brotherhood marks a solitude that can never be breached. The restaurant points back to a desire for what we do not desire, allowing us to satisfy that neurosis. But why is the Chinese restaurant’s “we” so often male — or why is the Chinese restaurant consistently a fixation for the white male author?

Perhaps the Chinese restaurant promises the (sub)urbanized man a zone where his imagination is contested and usually, but not always, triumphant. Whether set in a strip mall or on Broadway, the restaurant sustains an image of the world that includes more perspectives, real and imagined, than otherwise visible. In Christopher Guest’s mockumentary Waiting for Guffman, the Chinese restaurant reworks hustle and conspiracy for comic relief. In a Chinese restaurant in Blaine, Missouri called Chop Suey, Ron Albertson tells his acquaintance, the dentist Alan Pearl, about his botched penis reduction surgery. At the dinner table, eggrolls conveniently at hand, Ron stands up and begins to unzip, Dr. Pearl protesting, “medicine man not go near dances with stumpy.” Askew from Hopper’s vision, this scene imagines the Chinese restaurant as surreal, absurd, and uncanny, because it shows us a way of being and behaving we have repressed but not forgotten. Yet the line between liberation and exploitation is frayed — the cost of a social experiment is often the reduction of figures already on the margins to stock characters.

Via Whitney.org

Max Weber’s cubist canvas Chinese Restaurant (1919) captures this suspension of the ordinary within the frame of its exemplary form—the place where the social rule is overprescribed and overcome. Surrounded by a jumble of colors and shapes, gray vignettes offer a glimpse of diners in the restaurant. Weber contrasts a flow of unmediated sensation and the social order that occasions it. Such a contrast suggests the feedback between kitsch and avant-garde, or rather, their co-production. Mass culture becomes the material for artistic experiment, and vice versa. Hopper and Weber paint transgressive pictures about ordinary things, which in turn become ordinary pictures that inspire transgressive things. A cliché induces radical action, and radical action turns into cliché. Cubism is at the crux of avant-garde and kitsch when it describes the Chinese restaurant, synthesizing the pat-on-the-back and the harshest critique into a neutral observation. Chinese Restaurant can only show what is already there, in front of the image: the platform where we perform our loveliest nightmares.

There is a Chinese restaurant in St. Louis, Missouri, with a painting of an Italian man holding a bottle of wine on the wall. There is a painting of peonies, traditional, and a scummy aquarium. Fluorescent lights, space heaters in January, fans in July. Very spicy tripe, pickled cabbage, chicken gizzards with peppers, sliced fish in chili oil. The effect of Midwestern Chinese restaurants on the long arc of my own masculinity remains a mystery even to myself. From a canted angle, outside or above the picture frame, I might be able to detect its influence, to see myself as a lonely boy looking at a sculpture of galloping stallions mounted on the wall, an idle noodle dangling from my chin. Or as a lonely man, paper screens separating my search for intimacy from consciousness. But I am stuck on the canvas, like the woman with her back to the viewer in Chop Suey. If I could glimpse the crowd behind me, I would feel satisfied to have been the object of passing interest. I cannot help but suspect, however, that there is nowhere outside or above the frame for a crowd to gather. That the sense of isolation I desire, in small portions, is deeper, vaster, more permanent, than I can admit.

Jason Bell’s work has recently appeared in Guernica, Vice, The Brooklyn Quarterly, and Alimentum. He writes a monthly column for Full Stop about food and culture and lives in New Haven, CT, and St. Louis, MO.

This post may contain affiliate links.