I have been living in France for eight months now, and I have been taking anti-depressants for much longer. Wellbutrin, which worked well enough when I was taking 450 mg of it in the States, is, in France, only prescribed as a smoking cessation aid. Costing 144 euros per month, it is currently unaffordable. I began to take 50 mg of Zoloft, which worked fine because I didn’t feel awful all of the time. It didn’t work well enough, though, because I never felt like doing anything. Naturally, much of my time has been spent using a VPN service to watch Netflix. In my experience, our burden of being unspeakably alone is eased by a subscription to Netflix, especially if you consider that nothing happens after we die and then we just sleep forever, more or less. This being said, I’ve found France, particularly Toulouse, to be a very pleasant place to live.

I moved to France to teach English. This has not gone very well. Language schools aren’t eager to employ someone whose only qualification is completing a Teaching-English-as-a-Foreign-Language certification course where EFL teachers spend the majority of the 150 hours of in-class instruction teaching would-be EFL teachers English as a foreign language, instead of how to teach it, because that is the only thing they know how to teach. I wasn’t so naïve to think that this course would lead to steady work, mostly because there isn’t steady EFL work in France, but considering that Toulouse has the largest student population of any French city, I thought that I could teach at a couple of language schools, a couple of lessons here, a couple lessons there, and all together, with a few private students on the side, I could at least manage to pay my rent. I was wrong.

A very wealthy family, however, was renting out their guest house for very little money with two very wonderful little dogs named Junior and Phoebe that take naps with me and we have since become very good friends. The family never minds that the rent is late, but they do, however, want to be paid their rent, so they offered me a job doing manual labor at their company with flexible hours to accommodate what little teaching work I’ve found.

Unlike the hands of my father, who emigrated from Romania to the United States in the 80’s and has been doing manual labor his whole life, my hands are soft. My mother and my father made sure that I would never earn a living with my hands. I was smart, they said. I grew up very poor, but I would read books, and I would study, and I would earn my living with the head I was lucky enough to have placed upon my shoulders, my mother said. With the exception of my early teens, I have always loved books. I majored in philosophy. I graduated from an Ivy League university. Once, while visiting my father in New Jersey, I was reading at the kitchen table.

“What are you reading?” he asked.

“An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding,” I said.

“Oh,” he said.

* * *

Work begins at 8 am, and at 7:15 Junior and Phoebe scratch my door. I let them in, and we sleep together until my alarm goes off at 7:30. I eat breakfast, brush my teeth, and get dressed while they follow me. With my face sufficiently licked and their behind-the-ears sufficiently scratched, we part ways, and I ride my bike to work and arrive at 7:55. After getting coffee from the vending machine, I smoke a cigarette outside the break-room with Benoit, Gilbert, and Cedric. At 8 am, a bell rings, and five days a week I spend the morning doing a combination of hole drilling, rivet inserting, trailer emptying, caulk applying, screw turning, heavy-thing lifting, panel applying, screw removing, caulk-off-of-trailers scraping, a-goddamn-ladder finding, or screw, caulk, nut, or miscellaneous fetching. Two days a week, this is how I spend my afternoons.

In high-school, I swam competitively. I ran cross-county. Having been smoking for six years now, so long as I am not running, nothing at work is too physically challenging for me. I become sore, I stretch after work, and I feel very tired in the morning until 9 am, but my body feels fine. I have an appetite. I fall easily asleep very early. I realize the importance of all of the questions that my mother used to ask, the questions that I always lied about. What time did you go to bed? Are you eating? Are you exercising?

On my second week on the job, while installing a rivet without my gloves, my left palm scraped against an aluminum panel. I have a small scar now, where the skin peeled off. There are scratches on my forearm that I did not notice getting, and small cuts, now faded, on the joints of my fingers. During the 15-minute break at 10 am, drinking a coffee and listening to Julien and Benoit joke with Thomas and Aziz, I look at these marks on my arms, on my hands, and I admire them. I have told nobody that I went to Yale. Your hands are soft, they aren’t like mine, Cedric tells me in French, you need to wear gloves. Champion of the world, he calls me, after I scrape and pull all of the tar-sealed paneling off of the roofs of the trailers.

* * *

My previous routine was quite different from my current one. Junior and Phoebe scratched at my door. I let them in, and we slept together until my alarm went off at 9:30. Then I turned it off and we slept together until 11:00. Then, I might have eaten some tomatoes and leftover lentils for lunch if I was very hungry and not too hung-over, and if there were no leftover lentils I would make coffee and smoke a cigarette. I might have read, or more likely, watched a movie or binge-watched a TV show on Netflix until the afternoon, when I would ride the bus for twenty minutes into town for an hour of work. When I returned home, I would get back into bed and use the internet until I was hungry enough to make some eggs and lentils. I would drink very cheap box-wine, get back into bed, and use the internet until I went to sleep.

As James Thomson, the author of one of my favorite poems, A City of the Dreadful Night, put it, this was “death-in-life.” In this poem, I found a brother, who “travels the same wild paths though out of sight,” and it’s an incredible look into living with depression, personified as being a citizen of a city of perpetual night. The poem may seem melodramatic at times, perhaps due to a since over-use and dulling of the word “despair,” but what most don’t realize, because they’ve never themselves experienced it, is that Thomson didn’t exaggerate about those who suffer, mute and lonely.

If I ever get a tattoo, I decided that it would be a faceless pocket-watch, a reference to one of the stanzas that I know by heart, in which a fellow citizen is asked how life can proceed without faith, love, and hope:

As whom his one intense thought overpowers,

He answered coldly, Take a watch, erase

The signs and figures of the circling hours,

Detach the hands, remove the dial-face;

The works proceed until run down; although

Bereft of purpose, void of use, still go.

It occurs to me, though, that until they are run down, the works can run more or less smoothly. Standing in the brisk wind and watching the grey clouds that remind me of and make me homesick for New England, having spent the last week eating three real meals per day, having just helped Gilbert, an old man past the age of retirement who thinks once you stop working you die, move air conditioners, having gone to bed early, and having my arms ache as Benoit pats me on the back and says that I did a great job, I again feel a long-missing sense of vitality. I feel very good. Thomson asked if Death-in-Life can be brought to life again. It can, and though I will return to his city sooner than I would like to, my visits will be shorter and they will be less unpleasant due, in part, to my doctor having doubled my dosage of Zoloft.

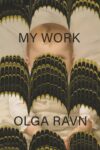

Image by Larissa Pham.

This post may contain affiliate links.