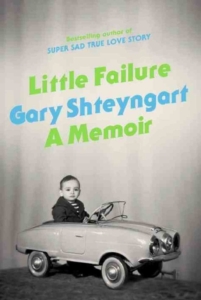

I’ve loved Gary Shteyngart’s work both for its pure excellence and, perhaps sentimentally, perhaps distastefully, definitely unfoundedly, because, just as Lena Dunham is or isn’t the voice of a generation, I want to peg him as the voice of a culture, a culture that is sort of my own; it’s this “sort of” that has drawn me even closer to his work in my attempt to understand my molecular form of third-generation Ashkenazi American-and-specifically-New-York Jewishness.1 It may be gauche to refer to one’s personal history in a book review, but since his new memoir, Little Failure, is a sprawling text that spans the author’s lifetime and teases the boundary between memoir and autobiography (memoir typically being far more engrossing), and since it sometimes falls flat in trying to capture an entire life in 349 pages, I responded to moments of personal affinity with the author as, in novels, I normally would with moments of climax. And then I narcissistically hungered for more of these moments.

Shteyngart plants himself in his works, scavenging from his past, and applying his nervous voice to all of his protagonists, essentially asking for our love. His books contain no moments of authorial intrusion — they are ALL intrusion. Many have asked, therefore, why he felt the need to write a memoir, given that he has already revealed so much. Is it a completely indulgent act by an author many see as too young to pen this type of literature? Did he decide he’s literary-celeb-enough to write an instructions manual to the ins-and-outs of his revered brain? Thankfully, not really. While, in the book’s weaker sections, there are occasional hints at this, the greatest merit of Little Failure is not that you’ll come out of it understanding Shteyngart, because who cares. Rather, it depicts the trajectory of immigrant assimilation in this country, and the fast disinheritance of the past that, at some point, either you or someone before you underwent to ensure that you function in the American present.

The character of Gary, née Igor, is introduced as a child and remains thus for the first 200 pages of the memoir. Shteyngart makes a bold choice in spending so much time on his distant past; it is, after all, the self that is temporally and developmentally removed both from his current self and his readers. The child’s perspective is so distanced from our own that, when failing to be poetic, its id-ishness becomes aggravating. But, knowing Shteyngart’s past work, as well as its many useful indulgences, this focus shouldn’t be disregarded as mere nostalgia or the author’s debt-payment to psychoanalysis (which Shteyngart later refers to as having “saved his life”).

Having endured hunger (as a child, the author looked forward to the butter sandwiches his grandmother would give him in exchange for his writing), the losses of countless family members at the hands of both German and Soviet forces, unreasonable institutionalization, and various other hardships, when Jimmy Carter bartered American resources for Russian Jews’ immigration rights, Igor and the Shteyngart family left Leningrad and moved to Queens. There, Igor was enrolled in Jewish Day School, where he wooed his teachers and classmates with his prolific novel-writing, purged himself of his Russian accent and traded Igor for Gary. In an act of defiance against the young Soviet self he’d been working to erase, the author took to bullying a younger Russian boy, mocking his accent and systematically twisting his fingers until he cried in pain, all the while quoting 1984.

At one point, Shteyngart recalls his mother showing him photographs: “’Two girls,’ my mother says, holding up the photo of her playing the piano in Leningrad, the dreaming, distracted child, and the other of her, a single-minded immigrant mother, behind the Red October in Queens, New York. ‘One as I was and one as I became.’” The author lingers on childhood, it seems, because here the greatest transition is occurring — from child into adult and from Russian into American, while his parents simultaneously transition from working-class to middle-class, moving from Forest Hills to Little Neck, mere doors away from the emblem of Jewish American prosperity, Great Neck. But despite the thematic importance of this age for Shteyngart, our visit with young Gary starts to feel like an interminable babysitting gig. After a while, the reader aches to hang with the adults.

Finally, for two chapters in the very middle of the book, the author is at Oberlin College, desperate for defloration, bemused by the student body’s alterna-egotism, and alienated by the agency shown by the rich “Obies” in their clean metamorphoses from beautiful, adjusted children of privilege into beautiful, agrarian socialists. For these chapters, having been in a similar situation at this very college, the author’s and my lives seemed to align in such a way that Shteyngart’s every word had me gripped, awaiting another perfect sentence to encapsulate my illiterate feelings about my own experience. That’s the beauty and downfall of a book that covers four decades of a person’s life in relative chronological order. Because of its lack of dramatic build and plot that meanders like a life, in bouts of displeasure with the book, I eagerly anticipated the moment Shteyngart would catch up to me age-wise and contribute his definition of a similar existence. He did, eventually, and here I felt connected — then, pages later, he began once again to slip away from me, into the unknown world of middle-aged adulthood.

There’s no point in calling Gary Shteyngart out for being self-involved; self-involvement is his brand, and it has worked wonders for him and his chortling, self-involved readership (from the mouth of one such self-involved chortler). Plus, he ensured that Jonathan Franzen beat everyone to the punch in his book trailer, casting Franzen as his analyst who scoffs at the book’s title and mutters, “More like Little Narcissist.” We should focus, rather, on the self-deprecation exhibited here — the self-deprecation that’s such a fundamental part of his self-involvement — and its origins. Just as he bullied the younger Russian boy, in Little Failure, Shteyngart confesses, “On so many occasions in my novels I have approached a certain truth only to turn away from it, only to point my finger and laugh at it and scurry back to safety. In this book, I promised myself I would not point the finger. My laughter would be intermittent. There would be no safety.” Shteyngart worries that in The Russian Debutante’s Handbook he’d written mocking versions of his parents. But, true to his word, they’re depicted in Little Failure with fullness and sweetness — he’s unreserved about their parental shortcomings, but always understanding, and so loyal. Generally, the book is far more mild-mannered than his novels (his adolescent circumcision, for example, is far less vile than the botched snipping that engenders Misha’s “purple bug” in Absurdistan). And, as with all of his writing, even with its comic bite, Shteyngart’s prose is some of the loveliest out there; it’s not often that a sentence’s perfection makes you broadcast, “That’s fucking beautiful” to the emptiness of your household from atop a toilet. But I did that. Lots.

Sometimes, of course, Shteyngart simply rambles, or gets caught up in cutesy details that a person’s aunt might fawn over more than their readers. Other times, my occasional impatience with the book had a lot to do with my (absurd) expectations of a parallel background from a fellow neurotic Jewish Oberlin-grad writer, and it was a somewhat upsetting realization that the intermittent indifference I felt in reading some passages about the author’s youth — up until he attends Oberlin and we share an experience — can be analogized, on a macro level, with the indifference shown towards immigrants, here and elsewhere, in their difficulty at mirroring the tendencies of the majority, their failure to make us feel ensconced in a landscape of our own facsimiles, most of whom were, at one point, immigrants. This book asserts that there is a collective pain underlying American existence, a shared loss implicit in all of our histories that so few of us fully grasp. It is experienced by those lacking and trying to gain visibility, and it is entombed with the ancestors of the well-adjusted. We might want to distance ourselves, but, says Shteyngart, “the past is haunting us. In Queens, in Manhattan, it is shadowing us, punching us in the stomach. I am small, and my father is big. But the Past — it is the biggest.”

1. Note the role of circumcision and Misha’s planned Holocaust (“mother of all genocides”) institute in Absurdistan, liberal arts college in The Russian Debuttante’s Handbook, family dinners in deep Queens in A Super Sad True Love Story, the withering appeal that comes with balding while elsewhere growing more hirsute, a humor of self-loathing.

Moze Halperin is an almost-Brooklyn almost-playwright and almost-author. He likes ham (from time to time).

This post may contain affiliate links.