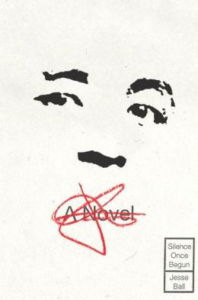

[Pantheon: 2014]

[Pantheon: 2014]

Narrator Jesse Ball is adrift — his wife, the love of his life, with whom he could share all of his secrets (and revel in hers in return), abruptly goes completely silent one day. Despite Jesse’s attempts to re-engage her conversational engine, their connection is severed, she leaves him, and he is left wondering what changed in her. He begins to seek out stories of other strange silences in hopes of finding answers, and stumbles across the story of Oda Sotatsu and the Narito Disappearances.

The disappearances took place a few decades ago in Japan’s Osaka Prefecture. A series of elderly people simply went missing from their homes, and nobody knew what had happened to them or who could have done it — until a young man named Oda Sotatsu signed a confession admitting he was the one who had abducted them, even going so far as to name three more people in the confession who hadn’t even been discovered missing yet. But as soon as Sotatsu was arrested, he never said a word regarding the crime.

It’s a testament to author Jesse Ball’s imaginative prowess that I had to look up whether or not the Narito Disappearances had actually happened before starting to write this review. While Ball prefaces Silence Once Begun with “the following work of fiction is partially based on fact,” by the end of the book I couldn’t be sure who or what had actually existed, so clear were the images in my head, so complex the philosophies and personalities of the characters involved. But no, the missing persons that occasion Oda Sotatsu’s confession and execution in Silence Once Begun never actually disappeared; author Jesse Ball completely fabricates the discovery and subsequent detailed oral history of this event.

Jesse’s attempts to delve into this event more deeply initially take the form of oral interviews (fittingly enough) with Sotatsu’s family members. The first section of the book inevitably ends up taking on a Rashomon-ic quality, as Sotatsu’s father, mother, brother and sister all get their say about what transpired during his time in prison, along with a prison guard who observed him. But Ball doesn’t let them fall into the he said-she said realm of one-note characters — these are fully fleshed-out people, whose thoughts, emotions and agendas are as real (and sometimes as contradictory) as your own. As such, Ball never lets you blithely ally with any one of their viewpoints or opinions. For example, when Jesse ends up befriending Sotatsu’s brother, Jiro, he prefaces his recorded interview with an admission of their close bond and speculates as to why their friendship might have suddenly blossomed:

In the meantime, Jiro had heard about my interview with his father, and had heard of the argument that had broken out (in his father’s estimation). It seems that by turning his father against me, I had obtained some measure of trust from Jiro. He was much more open and warm with me.

All of these conversations trace the outlines of a deliciously mysterious hollow spot where Oda Sotatsu silently resides at the center of the story. I can think of only a handful of mystery novels that have used intrigue and suspense as efficiently in the first hundred pages.

What first appeared to be a mystery quickly turns into a meditation on love. Jesse is able to track down Jito Joo, the woman who visited Sotatsu repeatedly while he was in jail. Jito Joo’s testimony occupies a middle ground between Sotatsu’s silence and the loquacious storytelling of his family members. She won’t tell Jesse her memories face-to-face — instead, she makes him sit next to her and study her in silence for hours before she gives him a handwritten account of her time with Sotatsu, asking only that he read it after he has left her apartment and that he not seek her out for answers to any more questions upon finishing it. Jesse’s preface to her letter mentions that he read it twice, put it down, got up to leave, looked back at it, then sat down to read it once more. With beautifully hypnotic passages like this, you can’t blame him:

The line of trees that is at the horizon — they are known to you. You have not been to them, you have only seen them from far away, always for the first time. One looks out a window into the distance, or comes down a circling drive, turns a corner. There in the distance, the tree line, all at once. It is dark here and there. It moves within itself, within its own length. It is merely a matter of some sort of promise. One expects that the forest there is nothing like anything is, or has been. I will go there, one thinks, and enter there, between those two trees.

Sotatsu, I said. I am those two trees.

Essentially, Ball poses the question: “Can any of us can truly know ourselves, let alone the others around us?” Every single character in the book has personal blind spots (whether willful or accidental) that are only revealed by the testimony of other characters. I appreciated the chance to continually ponder this as I made my way through Silence Once Begun — until I realized that any conclusion I arrived at, by its necessarily personal nature, would also have to be suspect. Perhaps this is how I finally came to understand Sotatsu’s silence.

Nathan Weatherford is a freelance writer disguised as an IT specialist at Powell’s Books in Portland, OR. He has been known to tweet from time to time.

This post may contain affiliate links.