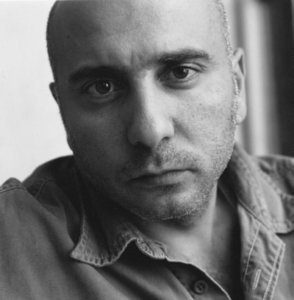

Awards and acclaim have collected around Rawi Hage ever since he published his debut novel in 2006. Although Hage came relatively late to novel writing, his first, De Niro’s Game, won the prestigious IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. Other awards followed for his second novel, Cockroach, and his third, Carnival, which was released in the U.S. just last month.

Born in Beirut, the now Canada-based Hage didn’t begin his career as a novelist — he arrived at writing via photography — and English is his third language, picked up through studies and taxi driving in New York City, where he moved in 1984. But writing novels in English is clearly his calling: “Once I discovered that I can write, or I should write, I immediately knew that this is the medium I should embrace.”

We sat down together at the 2013 Abu Dhabi International Book Fair.

M. Lynx Qualey: You’ve said you don’t like big book events and writers’ gatherings. Why are you here?

Rawi Hage: Frankly, I like traveling places and seeing other cultures. But basically, I have stage fright. Once I’m on the stage, I think I relax somehow, after the first couple questions.

I was never able to do it, but I admire writers like [Thomas] Pynchon who just from the beginning decided not to do interviews. Like Leonard Cohen. I admire them. I always contemplate it, but I’m not done yet. Once you embark on it, it’s kind of hard to track back.

You’ve said that you grew up surrounded by books. In French and Arabic?

In French and Arabic, yes. [They were] children’s books, and that evolved to comics. French, mostly: Tintin, Asterix, Spirou, and then “Livre de poche” and lot of Arabic poetry simultaneously.

Did you write stories in Arabic?

No, I never wrote stories in Arabic. I wrote something assigned by school, but no stories. I was a bad student. I always puzzled the teachers. The comments they would say were, “Bright, but lazy.”

How long did it take before you started writing in English?

It was a combination of many things. When I arrived in New York, I started reading in English. It was the ’80s, and there was nothing available in French or Arabic at the time — [it was] before the internet. So I started reading in English, and I did my studies in English. It’s circumstantial; it’s not a political decision on my part.

Do you still write in Arabic or French?

Only when I have to.

You’ve said that you attribute your style in part to Arabic poetry.

Yes. I suspect, I don’t know, I suspect that I can attribute my style to Arabic poetry. It’s not a definite thing. At least I permit myself to be overtly poetical in my writing. Maybe because I grew up in a culture that values poetry more than anything. Maybe.

These bursts come very spontaneous, I would say. But having said that, not all the writing is lyrical. It fluctuates to social realism sometimes, to different influences. So it’s a mixture of styles.

In an interview with the CBC you said that you’d promised yourself never to write about your life as a cab driver. Why?

When I was driving a cab, I promised myself not to write about that. I thought it would be kind of a cliché. I thought it was done.

You wrote about it in Carnival. What changed your mind?

It’s when I realized I can use it in a metaphorical way, taxi driving, and I slowly got sucked in. And it’s not just about taxi driving. Basically it’s about a carnival. And the taxi was a vehicle to pick up many characters. That movement, that circulation of the taxi driver, and this ephemerality, one passenger after the other, made the book like a series of vignettes.

Did you write it straight through, or did you write the vignettes separately?

The way I write is I’m a bit bipolar in my writing habits. I write intensely for a few months and then I take a rest for a few months. Then I come back to it.

So when you write, you write for hours and hours a day?

Yeah, intensely for three months. Very intensely. And I kind of get away from everything —internet, alcohol. It’s kind of regimented, but it’s also solitary. I get in touch with my inner madness.

Did you plan Carnival, for instance, before you went in?

I usually start my novel with an image or some vague idea of what the novel’s about. I’m not conceptual in my writing. I don’t do research. Not much of it is thematic. I don’t follow these methods. . . . I follow the story, but I brood on it for a while, too. I believe in thinking as well. I’m a bit Socratic in that sense.

How long did Carnival take you?

From the time I started writing it to the time was published, it took about four years. But the actual writing time is much less. It’s probably like a year.

In McSweeney’s 42, you did a beautiful job translating “Four Seasons and a Summer” by Youssef Habchi El-Achkar. But the translations of your translation were a bit unfortunate; it was as though it could be any “Middle Eastern” conflict, anywhere.

Yes, it wasn’t put in context. But he’s that sort of writer, an experimental writer. And he never denied his European and Japanese influence. It was that period when [Lebanese] literature was open to other influences. He was an existentialist writer.

And did you feel some sort of kinship? Is that why you chose him?

Very much. I never read him before, I’d heard about him, but when I read him, I felt like I’m some kind of reincarnation of this guy. I felt an affiliation with him on many levels. He’s somebody who’s open to Western culture, and sees some value in Western culture. And also he comes from exactly the same background — [we are both] minorities in the Arab world.

You’ve said that he’s perceived as a marginal writer.

He was a writer’s writer, all the writers read him. It was kind of a tragic thing, because all the Arab writers read him, but he didn’t get his place in the Arab world. And also, he left Beirut and lived in a village. Just by doing that, he was also perceived as being provincial. But I don’t think he was.

Do you also feel marginalized?

No, I’m not. I can’t claim to be, as much as I would like to be. But I think my books are getting less commercial, maybe even less accessible.

Do you think you have a freedom to do that, now that your name is established?

Yes, I do. I’m not undermining the merit [of any of the works], but yes, I do.

Are you working on a project now?

No, I’m not, actually. I’m just touring. I’m brooding, I’m thinking of something. I think I write my books before I put them on pages, so I’m writing without touching devices.

It’s not rational, as much as sentimental. I have to be in this frame of mind where I’m feeling pity for myself, and feeling pity for the world. Once I’ve attained the summit of this, then I have to sit down and write. With a vague subject, you know.

Would you ever consider translating?

No.

Why not?

It’s very laborious. I’m lazy. I’m not studious. I can’t focus for a long time unless I have a real passion for the work.

If you were going to, is there anybody whose work you’d want to translate?

I would translate from Arabic, actually. There was some kind of tent of experimentation, especially in Lebanon, in a certain period before the war.

I envy that era during the 1960s up to the civil war. There was some kind of revival and a very progressive community that formed in Lebanon, mostly around the AUB area around Ras Beirut. I hear from my uncles — one of them was a journalist and a novelist, and the other a novelist and a poet — and I hear their stories. And I think they attempt something. It was the end of the nahda (“renaissance”). They formed movements, actually. I think they did.

It was very political. But I would be tempted to go back, and maybe gather a few texts to translate, but that’s it.

Any particular author?

I think there’s Elias al-Diri, who attempts something. And Youssef Habchi El-Achkar. I’m more interested in the era [as a whole] — it’s a romantic notion of mine.

You said you don’t do research.

No, I don’t need it. I think a writer should rely a bit on experience and life and do as much random reading and exposure and see what happens. I think we should absorb as much as we can and filter through. I always give the analogy of the whale: just gobble a lot of water and keep the fish.

Do you ever teach creative writing?

I’ve done it once — on the internet, through a university, for one student who gave me her manuscript, and then we discussed it on Skype. And that’s the extent of it.

And you don’t have any interest in teaching?

I do, I would like to communicate at points. But my problem is I don’t believe in the programs of creative writing. I think they help certain people, but I’m against this homogenization of writing and it’s becoming such a big industry.

I think one should teach a student to read, not to write. Maybe to observe. There’s a lingo that I see in creative writing that I don’t understand. If I hear one more time somebody telling somebody “character development,” I’m just going to hurt somebody.

Do you think these creative writing programs have hobbled literature in some way?

I don’t think they should be abolished, they do have some benefits. They’re sustaining writers, many writers.

There’s no harm in a student being interested in writing. I’m biased because I never took any of these courses and maybe I’ve romanticized the idea of writing. It’s almost a religious call.

I think arts is a need, it’s almost a survival thing.

But you received your “call” later?

I started with photography, and I always thought it might fulfill that call for me. When I was living in New York, I met this photographer, and I assisted him in the darkroom. And I think he first time I saw an image surfacing in the developer, I was blown away. And I knew this was what I wanted to do.

I think the whole idea of art started with this image surfacing.

I think I was in the wrong medium, but photography helped me a lot, and through photography I was introduced to academic thought, critical thinking, and various books, when I did my degree photography. And that eventually led to writing.

But once I discovered that I can write, or I should write, I immediately knew that this is the medium I should embrace. It’s a wider space, I think, writing, in terms of narrative. Photography is kind of limited and leaves much to the interpretation of the viewer. But I think writing is much more precise in that sense.

Do you still do photography?

I still do photography for my own pleasure and I enjoy it very much.

What do you enjoy about it that writing doesn’t give?

I enjoy because there’s a proximity between me and the subject. It’s much more physical. With writing you’re immobile, but with photography you’re pretty much mobile. You have to move your ass, you can’t sit down. I enjoy that.

I feel I’m much more of an adventurer. And I do street photography, so you can imagine, it gives me a purpose to walk and see the city in a different way. It’s a pleasure for me.

Does it still feed your writing?

It must. I have a spatial memory. I don’t lose everything in the house. If you ask me where is a button, a red button, I can tell you precisely where it is. I’ve memorized the whole house, I know exactly where everything is. But I can’t memorize a text.

So how do you keep track of the whole of the text?

My writing is very spatial. That’s why I’m comfortable in first person, because I situate myself within these spaces where events happen. I’m constantly a witness, pretty much like a photographer — you have to be at a certain close proximity. I think that’s how my mind functions.

Plus, I’m a bit of storyteller. My name means “a storyteller,” so that was a bit of a prophecy.

M. Lynx Qualey writes about Arabic literature and translation issues. She blogs daily at http://arablit.wordpress.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.