In Los Angeles, around the area where Sunset Boulevard and Fountain Avenue converge, there is a huge building, the size of a city block and royal blue. This building is the main Scientology Center; the small road leading to the parking garage is called L. Ron Hubbard Way. Late last year, Paul Thomas Anderson’s movie The Master drew attention for being kinda-sorta about Scientology. But The Master was mostly about what the day-to-day business of being a cult looks like. I went into the theater expecting to be scared, but The Master basically just looked pretty.

In Los Angeles, around the area where Sunset Boulevard and Fountain Avenue converge, there is a huge building, the size of a city block and royal blue. This building is the main Scientology Center; the small road leading to the parking garage is called L. Ron Hubbard Way. Late last year, Paul Thomas Anderson’s movie The Master drew attention for being kinda-sorta about Scientology. But The Master was mostly about what the day-to-day business of being a cult looks like. I went into the theater expecting to be scared, but The Master basically just looked pretty.

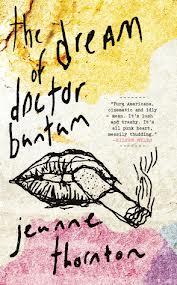

This was my context when I picked up Jeanne Thornton’s The Dream of Doctor Bantam. When most people read the word cult on the back of a paperback, they either think of the Illuminati or Scientology, and Thornton’s given a few interviews saying she was inspired by the latter. I assume other readers will bring some similar associations to Doctor Bantam, plus or minus Lawrence Wright’s recent treatments.

But I recommend leaving the Scientology context behind when reading Doctor Bantam. It would be a shame for readers to decide what the book will be like before they even crack the spine. The book doesn’t really function as an examination of life in one cult or another. Instead, it’s about what it is to be the kind of person susceptible to joining a cult — and how close we all are to being that kind of person. It’s also about what it is to be the kind of person who falls in love with someone in a cult, and how close we may be to becoming that kind of person, too.

The person who falls in love is seventeen-year-old Julie. Her wilder, older sister Tabitha recently died in what might have been an accident or what might have been a successful suicide attempt. Still mourning, Julie sees a girl on the street who smiles like Tabitha does. The girl is Patricia, a member of the Institute of Temporal Illusion; Doctor Bantam of the title is the completely unseen cult leader. Julie latches onto her new friend, taking a job in the apartment building Patricia manages on behalf of the cult and becoming something like a willing live-in servant for Patricia, who can barely manage to feed herself or count money properly. At the same time, Julie is coming to grips with her homosexuality and her attraction to Patricia. She worries she’s a pervert but cannot stop from masturbating in Patricia’s bathtub. The girls’ lives tangle together perilously as Patricia’s instability threatens to sink them both.

Julie’s perspective dominates the novel, an excellent choice on Thornton’s part. Spending too much time inside Patricia’s jittery head would be overwhelming. Julie is as fragile internally as Patricia, but that fragility is tempered with hardness. She loves Patricia but is constantly mean to her and disparaging of Patricia’s relationship with the Institute, calling it a cult even as Patricia tearfully begs her not to. Where Julie’s sister died or chose death, Julie works very hard every day to live. At one point in the novel, Julie symbolically takes Tabitha’s spirit into herself and chants “This time, survive.”

Julie’s adolescent confusion is both familiar and visceral, as in the bathtub scene I mentioned earlier:

She turned on the lights and the hot water and she set herself a deadline: by the time this bathtub fills up, you have to decide whether or not a pervert is the kind of thing you want to be for the rest of your life. She paced, her bare feet leaving ghostly footprints on the dirty tile and in the end, as she settled into the rising water, she still couldn’t decide.

Patricia’s fragility is successfully off-putting and worrisome while her sweetness and earnest striving to better herself make the reader understand Julie’s attraction to her and desire to care for her. Their twisted romance, the main thrust of the novel, is honest and exciting.

Despite the strong depiction of the main relationship, Doctor Bantam isn’t a completely successful novel. As I read, I felt there was something wrong with the book — something keeping it in the range of good instead of great — and couldn’t put my finger on it until I got to the “Intermission” halfway through the novel. Then I realized the problem: like in The Master, the cult wasn’t scary enough.

The “Intermission” is a transcript of an interview between an unnamed and unknown Institute member and Patricia’s ex-boyfriend Gregory. During the interview, Gregory is hooked up to a disturbing machine, the “Bantam Memory Elucidator,” and subjected to a special kind of Institute questioning. We know about the machine because Patricia used it on Julie earlier in the book. But before this “Intermission,” the cult was basically window dressing; all the fear I had for it was fear I brought to it from my own knowledge of Scientology and other cults. That fear was second-hand, not strong enough to feel viscerally. Without the danger of the cult looming, Patricia’s choices seem less foolish and Julie’s position less precarious.

Following the “Intermission,” the second half of the novel communicates that cult-y unease more thoroughly. Julie’s fuck-the-world attitude gets her in real trouble for the first time. One of her friends is driven out of town by a semi-fictional smear campaign, and Julie discovers the cult is responsible. Fear finally creeps into the narrative.

The novel’s final act is spectacular, as Patricia goes off the rails and Julie, at times too self-absorbed and at times too empathetic, clings to Patricia while failing to save her. The novel’s short last section finally plunges the reader into Patricia’s mind, and it’s like diving into freezing cold water, invigorating and excruciating. But the propulsive second half can’t erase the problems of the languid first section. I anxiously await Thornton’s next novel, but Doctor Bantam can’t be great.

This post may contain affiliate links.