“He’s making it up as he goes along. You don’t see that?” – Val Dodd to Freddie Quell about his father, Lancaster Dodd, in The Master

The title character of The Master, Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest movie, is Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman), who pioneers a kind of psychotherapy in the days following the Second World War that effectively becomes a cult – his followers refer to it as The Cause – with Dodd as the guru, the final and only interpreter of his own process. The movie, which has been taken very seriously, appears to be a satire, perhaps of EST or of self-help cults in general, though almost nothing that occurs in it makes much sense. The protagonist isn’t Dodd but Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix), a young sailor with a family history of mental illness who tumbles out of the war with post-traumatic stress and a drinking problem and happens upon Dodd and his devotees by accident.

Freddie loses a job as a department-store photographer after getting in a brawl with a customer; then he runs away when his homemade hooch nearly poisons a fellow worker on a cabbage farm in northern California. When he stows away on a yacht captained by Dodd – he borrowed it, as we learn later when its owner has him arrested and demands that he pay for the damage – their paths cross. Unaccountably Dodd is drawn to this unstable young man and takes him on as a kind of project, over the objections of his proprietary wife Peggy (Amy Adams), his daughter (Ambyr Childers) and his son-in-law (Rami Malek), all of whom find Quell’s alcoholism and his brutishness – he has a tendency to beat up anyone who voices objections to Dodd’s methods – liabilities. Presumably Anderson is using Quell as a way to expose Dodd and The Cause, but the two characters are equally preposterous and their relationship is as incomprehensible to us as it is to Peggy. At this point in Anderson’s career, however, after his 2007 There Will Be Blood, criticizing him for formal problems – implausibility, wobbly structure, scenes that don’t parse, characters you can’t believe in, dialogue that doesn’t sound like anyone in the history of the world could have spoken it, even (in this case) an elusiveness of purpose – is as ineffectual as trying to shake the loyalty of Lancaster Dodd’s most die-hard followers.

Anderson debuted in 1996 with an incoherent and unpleasant gambling picture called Hard Eight, but he didn’t garner notice until Boogie Nights the following year, an expanded version of a short he’d made almost a decade earlier called The Dirk Diggler Story. Boogie Nights has an enticing subject, the porn industry of the seventies and eighties, and though its view of porn in the seventies may be naively benign – it omits anything truly unsavory, like the Mafia, heroin, and kiddie porn – it’s amiable and fast-moving. And Anderson demonstrates a sophisticated technique and an engaging patchwork style; he steals from De Palma, Scorsese, Tarantino and especially Robert Altman.

The hero, a seventeen-year-old named Eddie (Mark Wahlberg) with a penis of legendary proportions, is discovered by a director named Jack Horner (Burt Reynolds) who invites him to join what Anderson portrays as a loving porno family presided over by Jack and his leading lady, Amber Waves (Julianne Moore). Boogie Nights is a multi-track narrative based in a distinctive community, like Altman’s movies, and it tries for the wild tonal variety Altman grooves on. But it falls apart almost exactly at the halfway mark, when it moves into the eighties and the characters, who seem relatively innocent before 1980, abruptly get swallowed up by drugs and violence. The last hour and a quarter is a series of absurdly hyped-up melodramatic scenes intended to illustrate the reductive notion that while the seventies were cool, the eighties were bad news. These episodes don’t work on their own terms, and some of them contradict what the movie has already established about the characters. The movie doesn’t contain any ideas that stand up to scrutiny, but like most people I know, I left it hopeful that with some seasoning, Anderson might end up being a filmmaker worth watching.

Then came Magnolia (1999), which was half an hour longer than Boogie Nights: three hours in total, though it seemed to last roughly a lifetime. Anderson shifts among nine major characters, all Angelenos, each of whom is linked in some way to one or two of the others. Earl Partridge (Jason Robards), a multi-millionaire on his last legs, begs his nurse (Philip Seymour Hoffman) to contact his estranged son, now a celebrity named Frank T.J. Mackey (Tom Cruise), who runs seminars instructing men on how to win the battle of the sexes. Partridge abandoned Frank and his dying mother when Frank was a boy, and for most of the intervening time he’s been married to a much younger woman, Linda (Julianne Moore), who is experiencing a crisis of conscience over the way she’s treated him. Partridge’s production company is responsible for TV’s longest-running quiz show, which pits a team of prodigious kids against a team of adults every week; like Earl, the show’s host, Jimmy Gator (Philip Seymour Hall), has terminal cancer. He’s trying to reconcile with his daughter Claudia (Melora Walters), a cokehead with a wretched romantic history who’s so rabidly furious at her father that we barely need to be told that he molested her. Claudia arouses the affection of a cop (John C. Reilly), who comes by on a disturbance call and ends up asking her out on a date. On the night Jimmy collapses on camera, the most brilliant member of the kids’ team (Jeremy Blackman) has a meltdown after pissing himself on the set and arrives at the conclusion that he’s being treated (by his greedy father, the production staff, and the audience) as a freak. Meanwhile a grown-up quiz kid (William H. Macy) who hasn’t been able to get his life together since he outgrew the show finds himself getting plastered in a bar after losing his job.

The commonalities that link two or more of the characters – cancer, bad fathers, drugs (Linda takes pills to combat her depression and hysteria), celebrity – swirl on the surface of the movie like an oil slick, but Anderson offers no overriding theme that they all might hang from. He pretends they’re connected: at one point they all lip-sync one of the Aimee Mann songs on the soundtrack, “Wise Up,” and in one humdinger of a scene each of them looks out a window or up into the sky and discovers that it’s raining frogs, an apocalyptic moment that has nothing, evidently, to do with the rest of the movie. Anderson told a New York Times Magazine writer that he refused to buckle under to pressure from the studio to pare his movie down because he wanted to say everything that was on mind, but whereas Boogie Nights contains silly ideas, Magnolia doesn’t seem to contain any ideas at all, unless you count truisms like sometimes urban legends are true or there’s someone for everyone or some fathers are lousy to their children but we you reach the end of our life we want to make amends with them.

In Boogie Nights Anderson showed some talent for directing actors, but here he refuses to rein anyone in; some of the cast – Walters, Cruise and Moore – seem to be engaged in a bad-acting contest that is all the more embarrassing by contrast to Robards, who plugs into some O’Neillian tragic depths of his own devising and is altogether astonishing. Once again Anderson’s model is Altman, but the Altman of Short Cuts, an amalgam of Raymond Carver stories that is far from his best. The best part of Short Cuts is the set-up, where you watch the balls being thrown into the air and kept spinning, but the thrill wears off fast when you get bogged down in the implausibility of the characters’ behavior. In Magnolia the credibility factor is low from the outset. Why doesn’t the cop, who’s trained to deal with druggies, notice that Claudia is strung out on coke, especially when she gets up about every five minutes to take another snort? Is it likely that kids on a TV show would be forbidden to run to the bathroom during commercial breaks? (1999 is long past the era of live TV.) Magnolia’s histrionics are reminiscent of the most self-indulgent work of John Cassavetes, but Cassavetes had some understanding of the mechanics of plot. Twenty-nine when he made this movie, Anderson didn’t know how to go on anything but his instincts, and they don’t seem to be terribly sharp. (If they were he wouldn’t have gathered so many gifted actors around him and then pull the kind of stunts a decent acting teacher would yell off the stage.) Magnolia isn’t a case of squandered talent, or talent gone disastrously wrong; it’s a case of arrogance passing for talent.

But instead of getting reamed for the overacting and the meandering, nonsensical plot and the lack of thematic unity, Anderson was declared a genius, and that assessment has gone pretty much unchallenged through Punch-Drunk Love (2002), There Will Be Blood (2007) and last year’s The Master. Punch-Drunk Love is an absurdist romantic comedy with Adam Sandler as Barry, a lonely man with seven interfering sisters and rage issues who falls in love with Lena (Emily Watson), whom one of his sisters sets him up with right around the time he’s blackmailed by a woman he made contact with on a phone-sex line. It’s a terrible film, though one of a kind for Anderson – its small scale and its quirky flamboyance are more typical of his namesake, Wes Anderson, another self-indulgent critics’ darling. By contrast, There Will Be Blood, a two-and-a-half-hour expansion of a 150-page section in Upton Sinclair’s novel Oil!, is vintage P.T. Anderson, for whatever that’s worth.

In the compelling early scenes, set around the turn of the twentieth century, Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day Lewis) mines along the west coast for precious metals, nearly killing himself in the process but surviving through a combination of grit and smarts. Eventually he turns his attention to oil, and by the time the main thrust of the narrative starts up, it’s 1911 and he’s a wealthy entrepreneur traveling with his little boy, H.W. (Dillon Freasier), buying up oil-rich land and offering the promise of civilization – a landscape dotted with roads, schools and churches – in return to the right to commercialize it. He winds up at a settlement called Little Boston, led there by an itinerant named Paul Sunday (Paul Dano) who sells him the information that the land belonging to Sunday’s unsuccessful farmer father (David Willis) is sitting on oil.

By this time the movie has already moved past the absorbing how-to-mine action section and settled into its true form: a parable on the destructive nature of greed. (There’s one more action sequence – an exciting, too-brief account of an oil-field explosion, which contains one magnificent image, superbly lit by Robert Elswit, of the black derrick flaming against an inky sky.) It’s obvious that Anderson set out to create a great American movie, and across the country critics dutifully fell in line, affirming that he’d triumphed, presumably because he’d left traces of all of his sources so they were easily identified: Greed and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, of course, and Citizen Kane and The Grapes of Wrath and, for the scenes involving Dano as Paul’s twin brother Eli, the revivalist preacher who asks Plainview to support his Church of the Third Revelation, A Face in the Crowd. Actually, A Face in the Crowd wasn’t a very good movie, but it did have director Elia Kazan’s kinetic theatricality, and though The Grapes of Wrath was essentially fraudulent it contained sequences audiences kept in their heads for decades, as well as a sterling Henry Fonda performance.

There Will Be Blood has size and an attention-grabbing star turn by Day Lewis, but it doesn’t tell a coherent story or develop a single credible character. The film isn’t self-aware but it’s terribly self-conscious, as if Anderson had walked around the set with a textbook on how to make a classic; for all its stylistic boldness, it doesn’t contain a single moment of moviemaking madness. But it does have a theme that appeals to a lot of people at this moment in American history: it’s a portrait of the American go-getter as a vicious, relentless, grudge-carrying misanthrope who suffers no competition and always ultimately resorts to violence because at the core he’s a nihilist who wants to rub it all out – other people, the earth. He’s no more human than the endlessly feeding oil vampire in Neil Young’s song “Vampire Blues.”

Reading the raves for There Will Be Blood, I wondered if the critics who claimed that Anderson can stand side by side with Erich von Stroheim, Orson Welles and John Huston had taken a recent look at their movies. In Huston’s Sierra Madre, the greed of the anti-hero, Humphrey Bogart’s Fred C. Dobbs, grows in response to a combination of the hardscrabble life that he and his cohorts live in Mexico prospecting and the temptation of the gold itself; as Dobbs slaves away day after day, his life reduced to the pile of nuggets building up with excruciating slowness, his imagination becomes distorted, and he starts to see his two companions as predators just waiting for him to make an unguarded step. In Greed, which Stroheim based on Frank Norris’s novel McTeague, all three major characters are a naturalist’s case studies, victims of the allied forces of heredity, environment and the pressures of the moment. We see hints early on of what they’re capable of, what brings out their most unappetizing sides, and then Stroheim throws a lottery winning into the mix and watches them grow into monsters like those plastic toys you submerge in water – except there’s nothing artificial about these characters. Welles’s Citizen Kane is a Freudian examination of what happens to a boy when he’s robbed of familial love and robbed of his childhood and given a bottomless inheritance in their place: he grows into a man who tries to buy up the world and the love of everyone in it. The three directors’ approaches to explaining tragedies on a large scale are different from each other, but what unifies them is that all their characters’ psychologies are personalized and dramatized. Sure, the films invite us to generalize about distinctly American kinds of personality, but those generalizations are grounded in specifics.

By contrast, There Will Be Blood begins with a generalization about American entrepreneurialism (it’s bad, it’s soulless) and gives us nowhere to go from there but back again and again over the same line. Oil! is a plodding piece of work, but at last Sinclair makes the character Plainview derives from life-embracing, with a taste for joyriding. Anderson doesn’t even retain that quality, for fear it might make us like the character just a little bit. He has no interest in presenting Plainview as a three-dimensional human being like Dobbs or Kane, so he doesn’t give us a hint of what shaped him; we’re meant to see him as having arrived fully formed, a blight on the American landscape. So Anderson doesn’t feel duty bound to write psychologically convincing scenes for him. In the most baffling sequence, a Standard Oil man, H.M. Tilford (David Warshofsky), makes Plainview a perfectly reasonable offer for the New Boston concern. By this time H.W. has gone deaf and (mysteriously) mute as a result of being too close to the explosion, so Tilford suggests, not unkindly, that Plainview might want to take a rest from his work worries and concentrate on his family. Plainview’s reaction is to threaten to steal into Tilford’s house in the middle of the night and slit his throat, and Tilford, stunned, asks him if he’s out of his mind – one of the few moments in the movie when a character speaks sensibly.

It’s not clear how any actor could make Plainview believable, but Daniel Day Lewis makes no attempt to. He substitutes bombast for character. A good actor, as Pauline Kael once pointed out, doesn’t just tell you what he’s doing; he tells you what it means. Otherwise all you get is surface. When There Will Be Blood is finished, you understand no more about Plainview than you did at the beginning – less, I’d say, because in the opening scenes the physical action conveys something about his determination to strike it rich and his ability to withstand the worst sort of adversity. Almost everything else he does in the course of the picture had me scratching my head. Day Lewis is charismatic in the role, and yes, he has that impressive vocal instrument, pitched to imitate (apparently) John Huston – part of Anderson’s nod to Sierra Madre, I assume. But the tricks he can do with his voice are just tricks – like Meryl Streep’s famous accents – unless they illuminate the character, and here they don’t. And though the movie has a beautiful rural burnish, Plainview is practically the only figure in it you want to watch; the actors hovering around him are emotionally immobile, so they register no more than so many flies stuck in the period flypaper. (The exception is Paul Dano, who’s so miserably miscast as the preacher that compassion compels you to look away whenever he’s on camera.)

The plot really isn’t very complicated, but scene for scene it isn’t plausible. Anderson doesn’t seem to think he has an obligation to work it through because he’s going for something broader and deeper and more important, but even if he actually did have more to say about American corporate mentality than that it’s always been with us, even if the character of Plainview were plausible rather than merely symbolic, it would still be incumbent upon Anderson to think through his own story line. (Greed, Citizen Kane and Sierra Madre all have superbly developed narratives.)

If you have no trouble buying Day Lewis as Plainview, then perhaps you can also accept Philip Seymour Hoffman’s mumbo-jumbo and tantrums in The Master. Hoffman is a splendid actor, but not in Anderson’s movies, where he sinks to self-indulgent playacting. (His turn as Lancaster Dodd includes scenes where he screeches obscenities exactly as he did as the thug in charge of the phone-sex line in Punch-Drunk Love.) The big scenes in The Master lack rhythm and shape, and you can’t get even the most basic idea of the relationships. Dodd appears to take Freddie on because his moonshine gives him a pleasant kick and at first he wants the young man to provide a quantity of it for the guests on the yacht. Then he tells Quell that he’s wandered from “the proper path” and gives him a taste of what he proffers to his followers, which is partly regression therapy that Dodd calls “dehypnosis” (he believes that our bodies store up feelings and events through a series of incarnations), partly oral questionnaires (“processing”), partly protracted, incoherent exercises that are meant to be freeing in some not-very-clear way. By the time the yacht lands in New York harbor, Dodd has decided that Freddie is the dearest boy he’s ever met and has taken him on as a kind of aide (though mostly what Freddie seems to do is intimidate Dodd’s enemies without Dodd’s permission). He keeps coaching Freddie, but he can’t get him to stop drinking or to stop embarrassing his organization; Quell’s intractability – the fact that Dodd’s therapy never seems to have the slightest effect on him – could be Anderson’s way of showing it up, but though that would explain why Anderson keeps him on, it doesn’t tell us why Dodd does. (Dodd’s occasional explosions at Freddie, like the scene where they wind up in adjacent jail cells, cursing each other, seem arbitrary.)

The movie expects us to believe that Dodd’s followers are so brainwashed by his charisma or their neediness or something that it doesn’t occur to them that he’s spouting nonsense akin to the kind you come across in Ayn Rand’s novels — any more than it seems to occur to the poor bastards who sign up for Tom Cruise’s seminars in Magnolia that no woman at the end of the twentieth century is likely to find his barbaric misogyny appealing. (I couldn’t understand why graduates of those seminars weren’t storming his offices, demanding their money back when they couldn’t get laid.) Anderson relies over and over again on the same kind of post propter hoc logic that a film like Paul Haggis’s Crash banks on. Its fans, convinced that America is racist through and through, are willing to accept the movie’s alleged proof, even though the scene, for example, where a white cop in the L.A. of 2004 practically rapes a well-dressed middle-class black woman in front of her helpless husband during a traffic stop challenges common sense. Similarly, Anderson’s enthusiasts don’t need an explanation for Daniel Plainview’s behavior in There Will Be Blood (he’s a symbol for corporate greed so he behaves like a monster) or for the credulousness of Mackey’s disciples in Magnolia (men are only too happy to be reduced to sexist pigs) or that of Dodd’s in The Master (once people subscribe to a cult they stop thinking for themselves). In drama, though, it’s the responsibility of the writer to explain how these shifts come about; we’re not supposed to take the writer’s word for it just because he echoes our own biases. These movies kiss the asses of their liberal viewers by congratulating us for having these biases to begin with. Anderson’s movies promote a second kind of fallacy, too: they encourage us to accept the symbol for the reality. But no matter what style it adopts, a movie with a conventional narrative has to be consistent with psychological realism; it can’t leap to the symbolic level and use our interpretation of those symbols to justify the behavior of the characters, no matter how Martian.

I didn’t buy for one second the world of The Master, where a walking time bomb like Freddie Quell would get hired by that department store. I didn’t buy Dodd’s party-game psychological exercises, or the episode where Dodd sings “I’ll Go No More A-Roaming” while his naked female acolytes (including his visibly pregnant wife) accompany him on a variety of instruments, or the one in which Dodd somehow tracks Quell down in a deserted movie palace by telephone and invites him to join him in England. I didn’t believe the scene where, for some unstated reason, Dodd and Freddie sit opposite each other while Dodd sings all of “A Slow Boat to China.” (This scene, like so many others, drags on interminably, as if Anderson had wandered off in search of a soda in the middle of the shoot and forgot the actors were still emoting in front of the camera.) I didn’t believe any of the dialogue, especially the lines that poor Amy Adams (who’s coached to act like a condescending WASP country-club society matron) is saddled with, like “You can’t take this life straight, can you?” and “This is something you do for a million years or not at all.” And God knows I didn’t buy the scenes at the beginning and end of the movie where Freddie dry-humps a sand sculpture on a public beach.

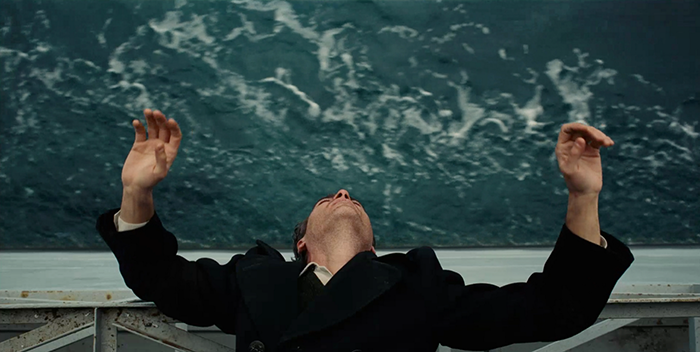

Hoffman — looking rather roly-poly and (in some scenes) suggesting a sloshed aristocrat at a cocktail party — and Adams give embarrassing performances. Joaquin Phoenix, though, is rather fascinating. He’s such an amazing actor that when he gives himself over to a role you can’t take your eyes off him, even if you don’t understand just what the hell he’s trying to do. He bends himself over in the early scenes, doing something weird with the side of his mouth and slurring his lines as if he’s had a stroke; then he puts his hand on his hip and sashays around. Late in the movie, his face looks ravaged. This is certainly a misbegotten piece of acting, but at the same time it isn’t hammy or self-conscious. Phoenix is the real deal, even in incalculable tripe like this movie. So is the cinematographer, Mahai Milaimare Jr.: the movie has the look of black-and-white art photographs from the late forties and fifties, and when the images are matched to evocative period music like Ella Fitzgerald’s rendition of the Irving Berlin ballad “Get Thee Behind Me, Satan” or Jo Stafford singing “No Other Love,” they work up a certain amount of emotional power, though again it isn’t tied to anything decipherable.

Whatever quacks like a duck, they say, must be a duck. But it doesn’t follow that if a movie looks like art, it must be art; if a filmmaker has to work as hard as Anderson does in There Will Be Blood and The Master to make his work look like art, chances are it’s dross – a scam. Anderson uses his self-importance as a director to extort admiration, and we can all see that it’s working for him. His movies are the Emperor’s new clothes.

This post may contain affiliate links.