Back in my college days (oh, for the lightweight days gone by), I used to quote Dorothy Parker whenever someone asked me about my drinking habits: “I love to drink martinis, / two at the very most. / At three, I’m under the table. / At four, I’m under my host.” Then I’d usually wink or giggle (depending on how many I’d had), and say, “That’s why I always stop at three.”

Back in my college days (oh, for the lightweight days gone by), I used to quote Dorothy Parker whenever someone asked me about my drinking habits: “I love to drink martinis, / two at the very most. / At three, I’m under the table. / At four, I’m under my host.” Then I’d usually wink or giggle (depending on how many I’d had), and say, “That’s why I always stop at three.”

The need to state my alcohol limit had more to do with making an impression than protecting my liver: one drink was a cop-out; two a good time; three a non-sloppy drunk time, where the drinking experience might be uninhibited but not so wild that it wasn’t fun. What I drank, and where I drank, was all about the face I put forward: a beer at the frats, a glass of wine with a professor, a Peppermint Patty shot at a party. (The theme: Catholic Guilt. The soundtrack: lots of Madonna and George Michael. The themed drink: chocolate syrup and Peppermint schnapps administered to the kneeled recipient by a friend wearing a priest’s costume and assless chaps.)

The art of drinking, and drinking in public, is all about codes — knowing your environment and knowing the art of conversation. If liquor loosens tongues, it also drags you out of the corner and into the culture of the bar itself. This is all beautifully captured in Rosie Schaap’s witty, compassionate memoir, Drinking with Men (Riverhead, $26.95), a meditation on learning how to drink well, wisely, and with eyes wide open. If you’re seeking a story of drinking gone wrong, you’re better off with Augusten Burroughs’ Dry or Mary Karr’s Lit, but if you want an elegy to good bars and a stiff drink, Schaap has you covered.

She writes about grown-up drinking, and each drinking story she shares marks a significant shift or conflict in her life. As a teenager, she’d dress like a Gypsy and offer tarot card readings on the Metro-North New Haven line for free beers; as an adult uncovering her latent spirituality, she’d find refuge in bars between stints as a volunteer chaplain at the foot of ground zero; as a married woman, it took a special bar in Montreal to feel her relationship coming apart. To be a bar regular, she says, is all about “adapting—and about enjoying people’s company not only on one’s own terms, but on others.” We go to bars to find ourselves in other people’s habits, and in finding other people, find ourselves. Three martinis or more, you’ll always find yourself under the sway of your host, and that’s the best part of bar culture.

Most persuasive in this book is the way Schaap openly acknowledges the shifting identities she experiences in each bar — how she slips into whatever mode or role helps her feel at home in a new place. The promise of the bar as communal watering hole is a fundamental part of the New York experience — and this town can promise as many different identities as drink choices. Schaap notes that in New York, “the rich have always been with us, and they have effectively taken over. . . . on this small island, less and less space is available to those who were, and are, responsible for so much of its identity and spirit.” Yet after reading Schaap’s book, I dipped into several iconic New York bars, sipping and eavesdropping and taking the temperature of the place, and it struck me that there is no better place to mix up your drinking identity.

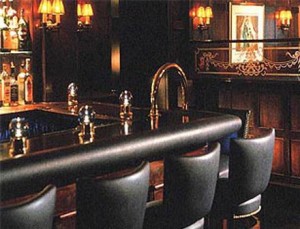

The rules, Schapp notes, are always immediately apparent, the “ways to behave, and not to behave, and each bar makes its own demands. There are loud bars where conversation is not a priority…there are quiet bars, lit low and engineered for tête-à-têtes.” Institutions of fine New York drinking, the King Cole Bar at the St. Regis, and the Campbell Apartment in Grand Central Station seem to be the latter — low-lit bars where the plush seats are filled with suited-up men and well-heeled women all balancing martinis precariously on fingertips. Yet if there are tête-à-têtes, they’ve more to do with transit than intention: the hotel and train bars are meant to be enjoyed and then quickly abandoned for other destinations. Even if you linger, as I was tempted to, you become quickly aware that you’re not meant to settle in, and certainly not with strangers. Though your gin & tonic may be impeccably prepared, bars require openness to fit Schaap’s criteria of greatness. “If you don’t want to talk, you might as well stay at home and drink and not bother.” (And the high price point of each drink, unless covered by another solicitous patron, will surely discourage you from staying too long.)

If you take a slightly lower road, you end up at the wide wasteland of the happy-hour circuit, the bars in Midtown East and West where the lighting is slightly higher and the drink prices slightly lower. This is where I first started to see what Schaap was drawn to in her favorite bars: the friendships between the patrons, and the warm greetings by the bartenders that recognize them. At the Archive, a little place in Murray Hill where the happy hour red wine was perfectly quaffable, I found a gaggle of midtown lawyers, each clinging to his bar stools and ordering an elaborately named scotch or whiskey of choice. “Can you believe how expensive it is to drink in NY?” asked a red-faced man in a too-tight shirt, leaning across my chair to snatch his vodka-and-soda. “It’s a luxury activity,” I respond, and we clink our happy-hour drinks in solidarity. A frizzy-haired woman to my left swished a diluted cocktail between her teeth as she complained about her work week to the bartender, but even she declined a refill. “I’m going to surprise my husband tonight,” she snickered, and then added, with a low raspy chuckle, “I hope it’s not a bad surprise.” Such confessionals would be out of place at a fancier bar, but watching people ease out of the workdays can be your first instruction in how to drink like a grown-up. Schaap said, “I’ve come of age in bars,” and perhaps the post-work drink is how you first observe functional adults at play.

Being a solo bar denizen makes it far more likely that you’ll be drawn into conversation, into uncharted territory and debate with a fellow drinker. I was drawn to the Blue Bar at the Algonquin because of its storied literary history (besides being the birthplace of the New Yorker magazine, it was the site of Dorothy Parker’s famous Round Table, probably the place of more than three-martini lunches.) If there would be any bar to emulate a certain kind of aloof New York society girl, it would be here — sipping a vodka martini with a twist, as smooth on the lips as chilled silk. But this is a place famous for conversation, and so when a white-haired gentleman settled down into the chair beside me for a martini of his own, I imagined he’d take an interest in my book and strike up a conversation. Yet his first remark to me was not on the state of literary fiction or on the merits of New Zealand-sourced vodka, but rather a comment on the Tiger Woods and Lindsay Vonn hook-up. “Says something about the institution of marriage, or lack thereof,” he remarked, the first of his remarks that would lead me to discover he was a visiting South Carolinian, passing through on a business trip and determined to enjoy his evening cocktail despite the CNN feed. But the martini proved to be liquid courage; I asked him to clarify exactly what he meant, and we ended up chatting for an hour about faith, traditional values in American culture, and the real peril (if any) our country might be in.

While I kept certain things close to the vest — my name, my occupation, my exact age, and my disagreements with most of what he said — I felt like I had wiggled under his skin for even just a few minutes, the alcohol having momentarily smoothed out our political differences. The bar-side chat can let you be as elliptical as you want to be, and perhaps the rule in New York bars, especially the iconic ones, is to “fake it ‘till you make it.” You order by gesture, and you make small talk that keeps the comfort level steady. For anyone afraid to drink out of their comfort zone, Schaap’s experience is beyond comforting: she treats the bar as “a leveler. Because as long as you can be here, be present as they like to say in therapeutic circles, be present in this bar, in this space, drinking and talking and listening, acting and reacting, you’re good.”

If the biggest takeaway of Schaap’s story is how each bar is one tier of the drinker’s comfort zone and confidence, then her experiences give me hope for drinking as a constant act of reinvention. The teenage Schaap, surrounded by “men in wrinkled suits and loosened neckties” begging her for a tarot reading, found a new sense of power. And while drinking at the Algonquin didn’t make me a writer, it did make me feel the rhetorical confidence that comes with a stiff drink and a persuadable companion. Yet even in her favorite bar spots, Schaap explains how much of her status as a “regular” was performative, meant to take her into a new community and place. “I was in the borderlands, neither here nor there, old enough to see that I was too young for the bar car, even though I desperately wanted to be there.” In the pursuit of a place to be, Schaap found her gift for capturing the voices and stories of her fellow drinkers, and found her voice as a writer glass by glass.

My last stop for the experiment, in tribute to Schaap, was far from a den of glittering cocktails, but rather a place of limited options and limitless cheer. Joining a friend at Jimmy’s Corner, one of the great dives of old New York, gave me the sense that the trappings of a great bar are only as good as the comfort you can extract from it. “A bar gives you more than drink alone,” Schaap says, “It gives you the presence of others; it gives you relief from isolation.” The walls of Jimmy’s are plastered with pictures of regulars and famous visitors alike, and though the beer choice is limited — under 5 choices on draft, about 8 options by bottle — and the tables wobble, I’m right at home. The alchemy of a cold Budweiser can be as powerful as that of the smokiest bourbon, and if this is a bar in Schaap’s wheelhouse, “no baloney here, no BS, no airs or fripperies,” I can see why she likes the atmosphere.

This post may contain affiliate links.