The first bookshop I worked at was in the middle of the busiest street in the hippest neighborhood in a city that prizes itself on being one of the most readerly places in the US. It had an eclectic clientele — everyone from blue-haired oldsters who’d grown up just blocks away in the days of streetcars to brawny bearded dudes in search of more-or-less artful pictures of male nudes to tech company dorks who never took their earbuds out. Tattoos abounded, and if you wanted someone to buy a particular book you didn’t talk about it because the customers were generally too cool to ask for help. Instead you wrote a recommendation card that said, “This is really weird — you’ll love it.” The walls were white, the aisles were wide, the books were symmetrically stacked, and people were drawn in by dozens of face-out covers in the windows, over-sized collections by obscure painters and cutting-edge designers. There were no cats.

The first bookshop I worked at was in the middle of the busiest street in the hippest neighborhood in a city that prizes itself on being one of the most readerly places in the US. It had an eclectic clientele — everyone from blue-haired oldsters who’d grown up just blocks away in the days of streetcars to brawny bearded dudes in search of more-or-less artful pictures of male nudes to tech company dorks who never took their earbuds out. Tattoos abounded, and if you wanted someone to buy a particular book you didn’t talk about it because the customers were generally too cool to ask for help. Instead you wrote a recommendation card that said, “This is really weird — you’ll love it.” The walls were white, the aisles were wide, the books were symmetrically stacked, and people were drawn in by dozens of face-out covers in the windows, over-sized collections by obscure painters and cutting-edge designers. There were no cats.

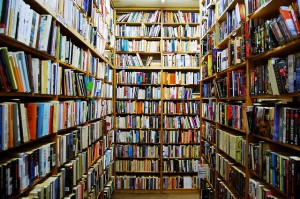

The second bookshop was in a suburban neighborhood of the same city, but it often seemed like it was in another country. The shelves were rough-hewn cedar, with antique typewriters in a line on top, and the floor was scattered with mismatched Oriental rugs. You didn’t have to align books carefully on tables, but you did have to pick up the ones that kids knocked over. Each customer was culturally pretty similar to the next, and if you wanted to sell something that hadn’t already been made into a movie, you had to spend a long time in conversation and you had to finish up by saying, “I know it sounds a little weird, but you might like it. Oprah did.” No cats, but you wouldn’t have been surprised to find one there.

I used to like to illustrate the difference between these places by juxtaposing two conversations. In the first case, in the first store, a woman approached the counter and said without preamble, “Do you have cunt?” I cocked my head and squinted. Having just come off a weekend marathon of every Deadwood episode ever filmed, my head was aswim with misogyny and baroque profanity. For a moment, possessed by the demon Swearengen, I thought to say, “We have such a superfluity, my doxy, that our whiskey no longer needs be stored in barrels.” But I remembered who and where I was before I spoke, and instead pointed her toward our women’s studies section and a book by Inga Muscio. Cunt, specifically. It’s a manifesto of female independence and self-esteem, and it regularly cropped up in the lower reaches of our bestseller list.

The second conversation came years later in the second store. Another young woman walked up and said, “There’s this book I’m looking for, kind of a women’s issues thing, and it’s named after a female body part, but I don’t want to say what it is.” A veteran by now, I told her I thought I knew the book she meant and called it up on the computer to show her the title. Vehement response: “NO! It’s like a health thing.” I couldn’t imagine what other book was so taboo it couldn’t be named aloud, so I showed her where she might look and left her alone. After a while, she returned to the counter in triumph with Boobs in hand. By Elisabeth Squires, subtitled A Guide to Your Girls.

I got a lot of mileage out of that comparison: one bookshop as forum for outspoken freethinkers versus another as refuge for herd followers and nervous nellies. I preferred the place where Murakami outsold Grisham to the one that stocked Sarah Palin alongside Barack Obama, obviously. But the more time I spent in that second store, the more I appreciated it. While the first store was visibly avant-garde, behind the scenes it couldn’t have been more traditional. Author visits were documented with a Polaroid camera in use since the 1980s, accounts were kept in pencil in a ledger, and the owner wanted nothing to do with newfangled notions like the internet. At store number two, the look was old but the owner’s ideas were fresh: daily electronic ordering of inventory, emailed newsletters, and an all-around willingness to keep up with the times.

Stepping out of a Chomskyite echo chamber turned out to be a benefit too. Sure, I had to grit my teeth and ring up the ravings of Ann Coulter on occasion, but that helped keep my faculties sharp. I realized something about the homogeneity of hipsterdom, and learned firsthand about the subtleties of suburbia. The most important lesson, though, was that presence is better than absence. Store number one closed not long after I left it, and store number two keeps chugging along in its fortieth year. Between Boobs and nothing, I’ll take Boobs.

This post may contain affiliate links.