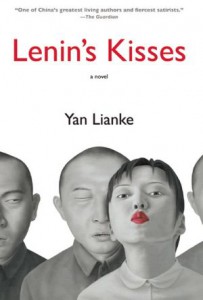

Lenin’s Kisses, the latest work from the acclaimed Chinese novelist Yan Lianke, now published in English by Grove/Atlantic, is a complex, if hyperbolic, portrayal of contemporary Chinese society. Its characters: peasants and low-level governmental officials live lives rearranged by the forces of an encroaching economy. Ultimately, the book’s goal is to address these forces with a combination of the fantastic and the absurd.

It is set deep in the Balou mountains, in a town populated almost exclusively by the disabled: the deaf, blind, dwarfed, paraplegic, polio-stricken, and all manner of cripples. For many decades they had passed quietly through life — worked the land each to their own ability, married, gave birth, and all the while remained so far out of the way that the town’s name, Liven, appeared on no maps. But in 1950 communism reached the countryside, and the village “entered society.”

The book begins when a summertime blizzard wipes out all of Liven’s crops. County officials show up to offer aid, but it soon becomes clear that County Chief Liu (the book’s deluded protagonist) has a history with this town and its residents, and what’s more he intends to exploit their disability-based “special skills” by enlisting them in what amounts to a traveling variety/freak show. The performers are paid, but the details are fuzzy, the boundaries always shifting; they are regularly ripped off.

Though Lianke portrays modern Chinese communism as greed calling itself equality, its capitalist successor comes off looking even worse. For one thing, Lianke’s capitalism is one big pyramid scheme, always promising ridiculous and impossible dividends. Chief Liu’s motive for forming the performance group is that the proceeds will be enough for him to purchase the decaying corpse of Vladimir Lenin and install it in his county, thereby making the locals endless tourism revenue. (Note the absurdity of making money to fund the possibility of making money another way.) This is how his ridiculous plan convinces as many people as it does:

He roared: One million a day, ten million in ten days, a hundred million in three months, and three hundred and seventy million a year. Three hundred and seventy million–and this would be just from the sale of admissions tickets. In addition to the Lenin Mausoleum, the Lenin Forest Park will also have…endless scenery for you to enjoy. If you climb the mountain to visit the Lenin Mausoleum, you will need to purchase a constant stream of admissions tickets, to the point that it will even be necessary to remain up on the mountain for a night or two. This, in turn, will involve paying for a hotel room and for meals. Even a box of tissues will cost two yuan. Just think, a tourist visiting the mountain will, at the very least, need to spend five hundred yuan? How much money would ten thousand tourists spend? They would give us five million yuan! And what if each of them were to spend a thousand yuan, or even thirteen or fifteen hundred yuan? And what if, during the peak tourist season in the spring, we don’t have ten thousand tourists a day, but rather fifteen, twenty-five, or even thirty thousand?…By that time, the question will not be how much money we can earn, but rather how we could possibly spend all the money that we do earn…How much can you possibly spend?…By that point, every family and every household will have so much money that their food will no longer taste fragrant, and they won’t be able to sleep at night. Each household will undergo extreme hardship in their attempts to spend the money. However, this is not my concern as county chief, but is rather an issue each of you must face, since it is a new problem encountered by Shuanghuai [County]’s revolution and reconstruction. It would take a much more capable county chief than I to solve this problem.

And capitalism has its more sinister outcomes as well, as greed eventually leads the “wholers” who traveled with the troupe to entrap these unfairly-wealthy cripples and brutally rape the three midget sisters. I wish this were hyperbole, but that’s the world Lianke’s characters live in.

It might seem petty to take issue with style when such important questions are at stake, but it seems to me that to make such critiques work in a novel, you should be equally as rigorous about your aesthetics as you are about your morals. And though I often wanted to like this book, to commune (no pun intended) with it more fully, it is just too clumsy, too lazy with its content. Take this metaphor describing the villagers in captivity:

They kept sitting or lying silently where they had been, trying to use silence to suppress their hunger and thirst. It was as if they were trying to use a mosquito to control a fire that kept burning ever hotter.

Frankly, I don’t know what to do with that. Does he mean to compare the relative sizes of a mosquito’s tubular proboscis and a fire hose? Or is the disjointed metaphor itself the intent, an expression of the impossibility the villagers face? I wish I could believe either justification, but this isn’t an isolated incident; too much of Lianke’s book falls similarly short.

On more than one occasion, Lianke veers into narrative clichés so brazen and unconvincing that I wondered if they were somehow unfamiliar to the average Chinese reader. For example: why does Chief Liu have such a fanatical devotion to the party and such a fixation on societal status? Because it was his adoptive father’s dying wish that he devote his life to ascending the ranks and become a great party leader, a man and a goal to which he keeps a secret shrine. On its own this would be merely cringe-worthy, but far too many of the characters’ motivations are similarly one-dimensional and unbelievable.

Still, amid clumsy sentences and a faltering story, Lianke has the ability to produce scenes of astonishing beauty. One in particular, involving a pack of feral dogs, brought tears to my eyes. Another describes the internal landscape of Tonghua, a blind girl:

She heard peoples’ searingly black shouts, their reddish black laughter, their whitish black applause flying back and forth through the air…heard [Chief Liu] give One-Legged Monkey his hundred-yuan bill and the latter kowtow in appreciation, knocking his head on the ground with a bright black sound.

If the book had been approached differently, had contained more of this sort of careful empathy, perhaps its criticisms would be on better footing when they do arrive. But that is a different book — one that was never written.

Although its publisher bills Lenin’s Kisses as “fiercely satirical”, this is wishful thinking. The characters are too one-dimensional, the story too rambling, the narration too naïve. And Lianke’s response to the brutality of humankind’s residence on earth is not to laugh bitterly, but to recoil, in horror and sorrow. Ultimately, this book is not a satire but an allegory. (The caricaturish character names — Deafman Ma, Parapalegic Woman, One-Eye, Polio Boy, even Chief Liu — certainly support this notion.) But in mistaking the two for each other, Lianke undermines his own cause. What could have been an engaging, sad, and often beautiful 200-page allegorical tale is here stretched and contorted into a 500-page satirical novel. It comes out much worse for the wear.

This post may contain affiliate links.