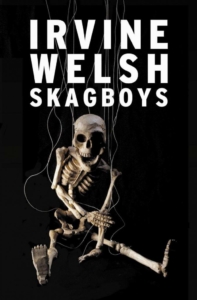

For his eighth novel, Skagboys, Irvine Welsh returns to the characters and setting of his debut novel, Trainspotting, and crafts a compelling lead-in to that work. The movie adaptation of Trainspotting became an underground sensation, capturing the zeitgeist of mid-‘90s “Cool Britannia,” but the novel is best seen as a dispatch from a grimmer place and time: the port of Leith in Edinburgh during the early 1980s under the Thatcher Administration. Skagboys starts with an overtly political tone, following principle narrator and protagonist Mark Renton as he and his father take part in a massive protest against an industrial plant undergoing privatization. Hundreds of union members and supporters arrive to find themselves outnumbered by a massive force of riot police trained and equipped, as one character notes, like an army ready to take on their fellow citizens. After a violent confrontation, Renton comes away disillusioned not only by the government’s actions, but also by the simmering undercurrents of Catholic versus Protestant antagonism found within the union ranks.

Periodic references to the political climate are scattered throughout the rest of Skagboys, but Welsh reinforces the importance of this initial scene by returning to it again as part of Renton’s rehab journals towards the end of the novel. The clarity Renton gains during detox gives the book significant weight as an exploration into the psyche of a drug addict, harkening back to the most powerful elements of Trainspotting. Renton writes candidly that he simply does not want to be clean, echoing the famous opening lines of the film adaptation: “Choose us. Choose life. Choose a career. . . . But, I chose not to choose life. I chose something else.” This is placed in stark contrast to periodic chapters titled “Notes from an Epidemic” that punctuate each section of the novel. Skyrocketing heroin use and the outbreak of AIDS in Edinburgh at the time are contextualized by facts about the eradication of working-class jobs, rising unemployment, cutbacks in social services, and implicit class warfare.

Welsh is a deft practitioner of psychological realism and plays to his strengths here, examining the group dynamic of a cast of his most familiar creations, detailing their orbits around one another. Chief among them are Renton and his friend and literal “partner-in-crime,” Simon “Sick Boy” Williamson, a born manipulator. It is undoubtedly the Renton and Sick Boy dynamic that drives the narrative. This double act allows Welsh to develop a post-modern take on man’s struggle with his inner nature and sexual morality. As heroin’s grip takes hold, Renton takes pains to sever his emotional bonds from his family and college girlfriend, while Sick Boy is canny enough to use junkie need to his advantage, both for his personal sexual gain and eventually his gain as pimp and pusher.

It is a book full of grim reality, dark humor, and constant abasement of characters’ lives, yet Welsh is able to provide scenes which contrast effectively with these elements, as otherwise psychotic characters, like Frances Begbie, are given fuller expression than in earlier works. Still quickly violent and a force of chaos, Begbie has the novel’s most poignant moment, crooning Rod Stewart’s “In a Broken Dream” as the characters ring in the new year, sharing a fleeting moment of togetherness.

Through the use of first-person narrative, writing each character’s dialogue (external and internal) in the phonetics of their Scottish dialect, and using their idiosyncratic patter and rhyming slang, Welsh makes the prose rip with energy. Once familiarized, it’s difficult not to have the word rhythms echoing in your head, from Spud’s “cat boy” ticks to Begbie’s profanity-laced aggro. Welsh has been criticized in recent years for scaling back on this stylistic device, and slyly addresses this concern via Renton’s rehab diaries, where the “posh” writing is crossed out to capture the real voice in his head (“youse” for “you,” “offay” for “off of,” etc.). As Renton notes, “That is more like how I sound in my head heid. Sometimes. Mair like. Sometimes. Why try tae sound different?” Readers new to Welsh’s work may find this off-putting, but through contextual clues it’s rare not to understand most passages, though specific cultural references to locations, food, and especially football (or “fitba”) teams and players can still baffle.

Serving as a prequel to Trainspotting, it’s clear there won’t be a “happy” ending to this book. But Welsh uses this knowledge to his advantage, taking time to round out major and minor characters alike in a way not seen in that earlier work. We meet the cast at a point in their lives with which it is easy to identify — young, seeking only weekend fun, and not shy about jumping into situations (or beds) purely for immediate gratification. The use of drugs recreationally never elicits a remark until long after heroin is introduced.

First seen as just another kick, the tipping point from casual experimentation to hardcore addiction isn’t revealed so much as experienced over the first hundred pages. And through all manner of trauma, the characters keep returning to its grip once more. Welsh concludes the novel with fitting ambiguity: Sick Boy and Renton, junk sick and desperate, in a doorway, about to make a choice.

This post may contain affiliate links.