Love is difficult to describe and even more difficult to rationalize. You love your father, but not in the exact same way you love your mother, and your love for both has evolved since you were a child. You love your lover in a different way entirely. Would you be able to quantify these different kinds of love? Could you rank them? In other words: whom would you betray first?

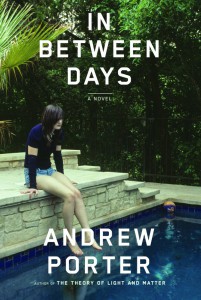

These questions — uncomfortable and, for most, not easily answered — serve as the central conflict for the characters in Andrew Porter’s debut novel In Between Days. They exist on a ground of shifting allegiances, and as they make their (often unwise) choices based on love, the reader goes through a cycle of understanding, frustration, and anger originating in the familiarity of the characters.

In Between Days, though not the most exciting title, is an accurate description of the state the Harding family is in. The parents, Elson and Cadence, have just divorced after a long marriage. The son, Richard, is adrift after graduating from college, and the daughter, Chloe, has been kicked out of school for her part in an attack by her boyfriend that has left another student unconscious, a crime that has political undertones. The Hardings are in stasis: frozen by fear, uncertain what will happen next, and untrusting of the decisions they’ve made to get them to this point.

The pairings become clear early on: Elson and Cadence are one unit, albeit a disintegrating one; Richard and Chloe another. Close in age, brother and sister share a bond made even tighter by the alienation they feel within their family. As children they exchange glances over the table at the hated nightly family dinners and create alter egos, Sean and Blaise, “out of boredom, or perhaps out of a desire to keep their own relationship at a distance from the relationship they shared with their parents.” As the older brother, Richard sees it as his duty to usher Chloe into adulthood, teaching her how to roll a joint and hide the alcohol on her breath when she sneaks in after curfew. Only later does he worry that his intentions may have led her off course, introducing her to destructive elements she may not have been attracted to on her own. Still, he finds himself unable to take a tough stance with his sister. He will do whatever she asks of him, even when it becomes clear that her loyalties now lie elsewhere.

The chapters alternate in point of view among the four Hardings, a structure that allows us to become privy to each family member’s secrets and preoccupations. We realize that Elson, the most unsympathetic character, has deeper emotions than his wife and children give him credit for, and that Cadence is afraid to let go of the past because without it, she has no way of defining herself. Richard’s storyline is the least compelling: he isn’t sure whether or not to apply to an MFA program in poetry. His self-doubts are meant to carry a lot of weight — to be indicative of the aimlessness of his parents, the uncertainty of his generation — but to me his excuses sounded weak and whiney.

Porter writes each character with sensitivity, which at times is his greatest strength. However, in doing so, he gives equal weight to the mundane and the extreme, occasionally stretching to make the characters’ trivial concerns carry more emotional weight than is warranted. Porter seems to be striving for a balance that doesn’t need to be there.

Chloe is the family member who breaks the stasis, prompted, of course, by love. Her feelings for her boyfriend Raja are intense in the way that college romances typically are, but taken off-campus and fueled by the prospect of criminal charges Chloe’s love becomes a full-blown, foolhardy obsession and the least believable relationship in the novel. She thinks Raja feels the same way about her, yet his actions come across as entirely self-serving. Chloe is supposed to be a smart young woman, and although smart people do dumb things for love all the time, her actions put her in too much danger, for too few reasons, for her not to wake up.

Despite these flaws, the novel is mostly successful, due to the unflinching honesty with which Porter examines the end of the Hardings as a unit:

And now they are sitting here together to eat, the four of them, as a family. In a year from now they will barely be talking to each other anymore. They will not even know the smallest details about each other’s lives. . . . But for now, they are here. For now, they are simply sitting together in a room, around a table where they have sat a thousand times before. They are eating a meal together, in silence. . . . They are doing what they believe, what they’ve been taught, families do.

As anyone who has experienced divorce knows, the disintegration of a family is acutely painful. Love that was supposed to last forever doesn’t end, exactly; rather it becomes transmuted into nostalgia for what used to be but is no longer livable. Through his close psychological portrait of the Hardings, Porter shows how bittersweet that change is.

This post may contain affiliate links.