- “Where passion is married to intelligence, you may find genius, neurosis, madness or rapture,” wrote Michael Chabon, in a special piece for the San Francisco Chronicle called “Ode to Berkeley” published in the summer of 2004. And, he continues, “None of these is really an unfamiliar presence in the tree-lined streets of Berkeley, California.”

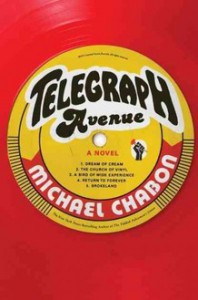

Chabon’s new book, Telegraph Avenue, takes its title from the main stretch that cuts through the outspoken city Chabon calls home, extending from Berkeley’s bustling college campus, through its overgrown jasmine bush-lined residential side streets, straight down to its southern sister, the sprawling untame of concrete Oakland.

The book takes place smack in the middle of Telegraph, in the borderlands between Berkeley and Oakland, at the fictional cultural institution known as Brokeland Records. A former barber shop owned by two devoted worshippers of the “Church of Vinyl” — the blundering but good-hearted Archy Stallings, son of former Blaxploitation movie star Luther Stallings, and Nat Jaffe, his endearingly neurotic, pinkly balding second half — Brokeland is in trouble. It’s 2004, and Gibson Goode, former N.F.L. star and black Oakland success story, is opening up a music megastore a few blocks down from the more-appreciated-than-profitable vinyl shop. But the business’s almost certain failure in the shadow of high-efficiency capitalism isn’t all that’s on Archy’s high-piled plate; his wife, the fiery-spirited Gwen Shanks, is extremely pregnant with their first child, and Archy has made the mistake of cheating on the wrong woman at the wrong time. In a parallel business struggle, Gwen and Nat’s wife, Aviva Roth, are facing the potential shut down of their midwifery practice, thanks to a prejudiced doctor and an explosive outburst from Gwen. On top of it all, Archy’s illegitimate 14-year old son has just showed up in town, and Nat’s very pubescent teenage son has fallen hopelessly in love with him. The intertwining plots allow the book to jump lithely from storyline to storyline, touching on issues of parenthood, sexuality, adolescence, and race, all woven together with a sometimes heavy-handed dose of movie and music history.

If The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay afforded those with a stockpile of arcane knowledge about comics an extra layer of the book to appreciate, Telegraph Avenue will be a hefty inside joke to those who know the complex formulations of contemporary hippiedom. Berkeley, as anyone who lives here knows, is imbued with its fair share of totally acknowledgedly nutty neuroses. It’s a place where a — albeit fragile — bliss can be obtained by the slow savoring of a perfectly-cooked heritage egg or a deep exhalation in a bendy downward-facing dog; where people are constantly so incensed by individual plastic packaging that it could qualify as borderline psychosis. (As Chabon puts it, “Nowhere else in America are so many people obliged to suffer more inconvenience for the common good.”) Chabon knows, intimately, the harsh tremblings of the Berkeley heart.

But how much of Telegraph Avenue is about the Oakland side of the avenue, and how much of it is a Berkeley fantasy about its southern neighbor? Judging from his track record — from the tragedies of World War II rendered in comic book retellings in Kavalier & Clay, to the heartbreakingly youthful nostalgia for youth in Mysteries of Pittsburgh, to the Sherlock Holmes-esque puzzlings of The Final Solution — Chabon can’t be separated from his aching nostalgia and whimsical tropes. Similarly, Telegraph Avenue’s heart is firmly rooted in taking delight, rather than somberly considering, the turmoiled place in which it is set.

Despite a scene of graphic violence well-woven in the deepest reaches of the book’s plot (a second scene of violence takes place with almost frustratingly comic effect), Telegraph Avenue is not a story about the sad daily violence of Ghost Town. Chabon is not writing that book. Though this can for a while seem somehow wrong for a book whose setting could afford thousands of tellings of human betrayal at the hands of racial injustice, and which sees too few, Chabon instead addresses race through the common human thread of nostalgia — nostalgia for vinyl, for old Blaxploitation flicks, for childhood’s achingly good donuts, for Bruce Lee, and for “every birth everywhere, all the vectors of human evolution and migration originating and terminating” at the parting of a woman’s legs.

Some will argue that this insistence on the obtuse is the work of a fetishist or an obsessive collector of whimsy. I’d say that’s true, and I’m not sure Michael Chabon would really deny that either. In his closing to “Ode to Berkeley,” Chabon argues that Berkeley is best captured in its insistence on small businesses for every seemingly absurd niche — the soda fountains, science ephemera natural history shops, vegan donut spots, and endless specialty used book stores that line its main stretch. Similarly, Telegraph Avenue ends with an homage to the passion that drives these peculiar establishments. “It was all about the neighborhood, that space where common sorrow could be drowned in common passion as the talk grew ever more scholarly and wild.” This is the spirit that drives the fictional Brokeland Records, and it is the same spirit that drives Chabon’s work. While it may not be rooted quite so strongly in the joys and difficulties of reality, it is at turns — like Berkeley itself — rapturous and mourning.

This post may contain affiliate links.