[University of Arizona Press; 2012]

[University of Arizona Press; 2012]

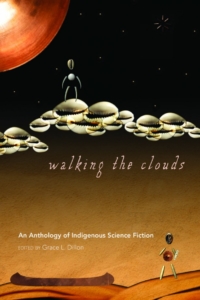

Ed. Grace L. Dillon

For the geeky Indian tired of reading and watching science fiction about white heroes conquering red planets, Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction is what the recent release of The New Yorker Science Fiction Issue was for other nerdy types—the validation of something that has for too long been ignored. In this case, not just the perennially-overlooked Indigenous voices but the weird Indigenous voices of speculative and science fiction.

Edited by the ever-insightful Grace L. Dillon, Walking the Clouds is the first anthology to bring together writers from around the world representing not only their own tribal literature but also the burgeoning movement of Indigenous futurism. This inherently radical literature dares to project the Vanishing Indian, victim of genocide or modern despondency, far into the future and onto a genre that re-envisions the world through uniquely Indigenous perspectives.

Walking the Clouds is not just an introduction to what Indigenous Futurism is, but a continuous attempt to create the subject of its study. To that end, the stories and excerpts are rather short with Dillon’s introduction and analysis defining and guiding us through the conceptual framework of each brief piece. The book is more an encyclopedia of ideas than a true collection of stories, providing a useful road map thorough previously scattered works while pointing out valuable sources to revisit.

The driving tension of this exploration is between what Indigenous futurism shares with science fiction and what it subverts. For Stephen Graham Jones, a self-proclaimed follower of “Blackfeet physics,” the time-bending, multidimensional quality of science fiction is simply an extension of tribal tradition. Neither Dillon nor I would go so far as to say all Indigenous literature is inherently science fiction, but what this anthology does reveal is that Indigenous science fiction is not new: it is simply a new way to group aspects that have shot through certain Indigenous literature and perceptions for a very long time.

Though Dillon points to these shared aspects, she is also quick to highlight the stark differences between a world centered on Western science and one on Indigenous knowledge. By choosing to lay claim to science fiction, the collection commits an ultimate act of appropriation by transforming a genre that has defined Western-American attitudes towards race, colonialism, and technology into a vehicle for Indigenous resistance. Aliens are no longer the racialized other of exotic worlds and the colonization of distant, presumed-empty lands no longer the central drama. Most importantly, Western technology is no longer revered as God but rather critiqued as a flawed method of interacting with nature.

We witness this war of worlds in Simon Ortiz’s contribution to the anthology, “Men on the Moon,” the story of an old Acoma man, Faustin, who turns on the television for the first time and watches the Apollo 11 rocket launch through snowy static. As he watches astronauts collect samples, Faustin laughs that the “American scientists went to search for knowledge on the moon and they brought back rocks.” When he asks his grandson what they want to learn from rocks, he is told the scientists want to know how the universe began. Faustin responds incredulously, “Hasn’t anyone told them?”

In Faustin’s eyes, the wonder of science and its ability to make anything possible — a theme in many science fiction stories — becomes skepticism and even ridicule of science’s attempt to “discover” what for many has already been found, much like the “New World” itself. Ortiz does not rely on how a Western notion of science can enhance his fiction, but instead reveals the fiction behind science’s claims to epistemological mastery. Ortiz’s story, “Men on the Moon,” is not in an anthology of science fiction because of its references to space and strange machines, it is there because of the process of estrangement whereby it challenges the precepts with which we classify “science” and “fiction”.

The disruptive estrangement of Ortiz’s work is the unifying theme of Walking in the Clouds. So too is the sense of irony, sharpened to a point in Stephen Graham Jones’ description of a robotic Lone Ranger subservient to Tonto and Sherman Alexie’s telling of a future world where Indians rid the world of all white presence. But nowhere is the topsy-turvy nature of the Indigenous futurist world clearer than in the apocalyptic frontier. Dillon argues that the science fiction apocalypse has long been an excuse for Western writers to re-open the frontier as a stage for the ongoing battle between savagery and civilization. But that imaginative space is quite different when experienced by people who, as Mark Bould says, “have already survived the apocalypse.”

From the perspective of Indigenous survivors, the frontier, whether the Wild West, Mars, or the ruins of a nuclear disaster, becomes less of what Vine Deloria Jr. describes as “a testing ground for abstract morality,” and more a “comprehensive matrix of life forms.” In short, Flash Gordon will not survive the Indigenous space age without serious re-situating his relationship with the universe. In Walking the Clouds, the brave white adventurer is sent groveling to the Indians who always continue to survive while the earth or some version of it responds to environmental crisis.

In Gerald Vizenor’s Darkness in St. Louis: Bearheart, an early classic of Indigenous science fiction, the crisis is the depletion of gas resources in America. Spurred westward in search of more fuel, the government eventually makes its way to Indian land. In this passage, Proude, an Annishnabe man, scares away federal agents who have come to make a deal for the timber on his land:

The federal man was so unnerved by the sounds of bears and harsh crows that he picked up his machine and started running, not pedaling, in the wrong direction out of the woods. The federal woman stopped him and encouraged him to return to the cabin. She reminded him of their responsibilities as elite employees of the federal government.

The mocking condescension of the last line brings a knowing smile to the Indigenous reader. Elite, ha! In this world you are revealed as the fools you are. But this is more than a spoof on white people (a genre that has existed in tribal literature for some time). The mockery here decorates a profound criticism of Western supremacy, the thinking so central to American identity that the conquest of Indigenous peoples is justified by the tautological superiority of civilization over savagery.

The speculative fiction of Indigenous writers peels back the benevolent mask of the colonizer, with his promise of progress, rationality, and hierarchy, to reveal the reptilian face of a hungry monster. Vizenor especially points to this darker side, this “fundamental savagism, which was always a part of Western civilization.” In Vizenor’s view a world dependent on ravaging natural resources is not truly advanced. It is simply brutal, and ultimately self-destructive.

While Vizenor argues that the post-apocalyptic Western subject has no institutions to return to, the Indian, even in the face of disaster and chaos, has a wealth of tribal knowledge and support to lean back on. The enduring message from Walking the Clouds is not just one of Indian survival but the ability for the Indian to make their home anywhere….even in a genre that as Dillon says arose in a context “profoundly intertwined with colonial ideology.”

This is exactly the case in Star Waka, an epic poem by Robert Sullivan, which details the journey of the Maori as they search for a new home in a different solar system. Though they soar into uncharted space far from the islands of their ancestors, their expedition is based on the tenants of Kaupapa Maori, or the “effort to combat the dehumanizing effects of colonization by maintaining the Maori language, culture, teachings, and philosophy.” Sullivan conveys this flexible identity by weaving traditional Maori terms with the technology of inter-galactic travel: “A space waka/ rocketing to another orb/singing waiata to the spheres.”

These few lines capture all the excitement of my initial thoughts upon encountering this anthology: Yes, Indians in space! To be an Indian in space, singing traditional songs to new planets, is to blow rocket smoke in legacies of dispossession and death. An Indian in space is a proud symbol of how far our Indigenous traditions can take us if we only dare to take them with us. Walking the Clouds takes us there, to space, to the future, and illuminates a new universe of Indigenous imagination that is both exhilarating and beautiful.

This post may contain affiliate links.