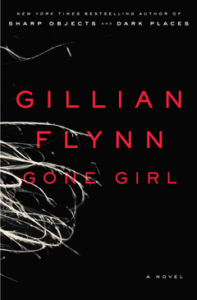

[Crown; 2012]

I believe that the best review of Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl must include a discussion of the mystery’s revelations, not just its set up. The first part of this review assumes that you have not read the novel and don’t want to know what happens (and, in my humble opinion, serves as a perfectly fine assessment of the novel on its own). The second part of this review assumes that you have read the novel or don’t care if you know what happens.

PART 1

Gone Girl gives and gives and gives. Like a generous spouse, it gives everything a reader could want from a mystery novel. It gives a persistent sense of dread and oncoming danger. It gives strong characters caught up in the dread and danger. It gives wit and snappy dialogue. It gives small puzzles, riddles that need to be solved in pursuit of a larger revelation. It gives readers opportunities to do a little clue gathering of their own. (My favorite part of a mystery novel is trying to figure it out before the author reveals the answer, my own ticking time bomb to defuse.) It also gives a couple of things not essential to a mystery novel’s success, but which many readers find satisfying nonetheless: multiple unreliable narrators and deft cultural critique.

The novel’s two protagonists, Nick and Amy, were once a happy, sex-positive couple, both magazine writers partially living off Amy’s trust fund while carving out a nice, Pinterest-esque life in New York City. When they lose their jobs and the trust runs out, however, Nick convinces Amy to move to his hometown in rural Mississippi, where he opens a bar with his twin sister. Nick and Amy live miserably together for another year, until their fifth wedding anniversary, when Amy vanishes.

Amy’s disappearance is not a scene from Murakami or Galchen — it’s a crime scene. An ottoman has been overturned, and the police discover evidence of blood, lots of it, spilled and cleaned up in the kitchen. As the police investigate, Flynn takes the reader deeper into Nick’s subconscious, unraveling the mysteries therein, and by the time the police begin to suspect Nick is the killer, the reader suspects him, too. There’s something very fishy, and Nick is the one who smells. He is arrested — wrongfully, he insists over and over again — as a Nancy Grace pastiche skewers him on national television.

Throughout Gone Girl, the narration shifts at each chapter break, from Nick’s perspective on the days following Amy’s disappearance, to entries from Amy’s diary that cover the relationship from the day Amy and Nick met. Flynn uses this device fantastically. At the beginning of the novel, while Nick comes off as a bereaved husband, Amy’s diary entries corroborate his story by detailing the blissful early years of their marriage. As Nick begins to seem guilty, Amy’s diary describes the deterioration of their love.

Flynn’s other narrative juggling act places the reader deep enough in Nick’s perspective to access his most private thoughts and feelings while simultaneously allowing him to keep his deepest secrets, including his whereabouts on the morning of Amy’s disappearance and the purpose of a mysterious second cell phone, to himself. Flynn handles this tightrope walk (to keep the circus metaphors going) perfectly, building suspense as she goes.

Perhaps the best of the little mysteries Flynn offers the reader is Amy’s traditional anniversary scavenger hunt. Prepared by Amy in the days before her disappearance, the hunt keeps Nick active during the police investigation while excitingly hinting at a darker side to Amy’s character. Nick follows the clues, not knowing where they will lead, and Flynn draws us closer to the truth of Amy’s disappearance as the two searches tangle and complicate each other.

PART 2

The book described in the first part of this book review (and in most other reviews) is not Gone Girl. It’s the first half of Gone Girl. Because in the middle of the novel — page 215 of 419 in my hardcover copy — the book changes.

Gone Girl doesn’t just shift or expand, it turns itself inside out, morphs, because at the novel’s midpoint, the central mystery is solved. Flynn reveals what happened to Amy, and for the rest of the book, which I consumed even more voraciously than the first half, the question becomes: what’s going to happen next?!

The novel’s most emblematic moment occurs just after Amy and Nick are reunited, from Nick’s perspective:

I held her to me and howled her name right back: “Amy! My God! My God! My darling!” and buried my face in her neck, my arms wrapped tight around her, and let the cameras get their fifteen seconds, and I whispered deep inside her ear, “You fucking bitch.” Then I stroked her hair, I cupped her face in my two loving hands, and I yanked her inside.

The novel’s second half unfurls Amy, who is not the frightened wife described in the diary, but a conniving semi-sociopath, framing her husband for murder for the crime of taking a mistress. The novel spends its first 200 pages transforming Nick from a mild fuck up to a possible killer, with Amy as the sympathetic one, the abused woman. Then, Flynn switches things, making Amy the villain and Nick the sympathetic husband, hunted by his wife.

In the first chapter of this second part, Amy refers to “Diary Amy, who is a work of fiction.” Amy is not only a master manipulator, but also a transformer. Diary Amy is an on-paper reinvention of the self; there’s also Cool Amy, the version Amy used to seduce Nick and Actual Amy, who is, like people are, a much more amorphous being. These named versions of Amy begin as masks that Amy wears to get her way, but as the novel proceeds, they become something closer to the different versions of self that we all have.

Flynn gives us Diary Amy for half the book because, while aspects of Diary Amy’s life are simply lies, many of her experiences and feelings are truths or half-truths. Even when Amy kills, we never really shake the sympathy for the woman we spent half of the book with. And we’re not supposed to. She’s always there, a part of Amy, and understanding her is essential to understanding Actual Amy.

By the end of the novel, Flynn has transformed her protagonists into antagonists, manipulating each other over and over again, forever united in a destructive matrimonial dance. Nick hates Amy but truly knows her for the first time; Amy doesn’t really care about anyone but has compelled Nick to behave like the husband she’s always wanted. Their careers have even turned around. Amy has a book deal for a tell-all memoir, and Nick’s bar has finally begun to turn a profit. (This serves as a nice resolution to Flynn’s critique of the professional writing culture: once Amy and Nick’s lives turn into a true crime reality TV show, they get paid again.) Their life together is a lie, but just a bigger version of the lies we all live.

This post may contain affiliate links.