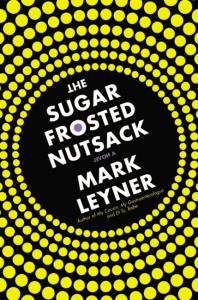

[Little, Brown and Company; 2012]

[Little, Brown and Company; 2012]

Recited by drug-addled, blind bards as they drum orange soda bottles, The Sugar Frosted Nutsack is a Homeric-style epic about a group of gods and goddesses living in the world’s tallest skyscraper who spend their days watching over Ike Karton, a former butcher from New Jersey who believes he is fated to be assassinated by Mossad agents.

That the title of Mark Leyner’s new novel shares the title of this epic — that we’re dealing with a book within a book — is the first of many dense layers to come. Our narrator focuses more on the reception of the tale than the characters within it and frequently veers off on tangents about the academics (J.D. Salinger among them) and conspiracy theorists that have analyzed it. More postmodern antics arise from that the fact that every time anyone mentions or discusses the epic, their words are “officially subsumed into the story.” The bards have to include these new lines into every future performance. If you initially have a headache from piecing this together or trying to explain it to a friend, rest assured you’re not alone.

Despite these heady layers, The Sugar Frosted Nutsack primarily operates on the sentence level. As Adam Sternbergh notes in his recent profile of the author, Leyner’s work strives to “instill delight, on a sentence by sentence basis — to create the vertiginous feeling in the reader that literally anything might happen next.” Leyner certainly achieves half those goals. Anything might, and does, happen; I never expected to stumble upon this description of two gods’ sex life: “Once he made her fifty feet tall and put the mummified body of King Tutankhamen into her ass as she came. She liked that so much that he turned Lenin’s corpse and Ted William’s cryonically preserved head into anal sex toys too!” Or a scene where bards begin making up new parts of the epic by creating phrases based on letters from license plates:

ZUP: Zipped-up pussy

BFV: Best fisting video

SRL: Sadist Rapes Limbaugh

AAJ: Anime Amputee Jamboree

Vulgar, yes; delightful, not so much. The narrator insists that, though it might read poorly on paper, “cringe-inducing smuttiness and off-putting adolescent scatology . . . completely come alive when delivered by vagrant, drug-addled bards.” The Sugar Frosted Nutsack is constantly justifying its recursive structure and overwritten, indulgence passages. As the story went “around in circles, in these sort of endlessly spiraling recapitulations,” one audience member complains, “it felt like, at some point, it was just going to drive me crazy.” The structural and sophomoric games continue even after the narrator admits how maddening this thing is to read. There never seems to be a goal in mind here beyond amusement, especially amusement for Leyner’s sake. “Although this is self-serving and unsubstantial bullshit,” his narrator writes in a moment I couldn’t help but read as a kind of self-satisfied confession, “it is upscale, artisanal self-serving and unsubstantial bullshit of the highest order.”

I understand that these moments of self-consciousness are all part of the point, another meta-commentary stuffed within a book bursting at the seams with meta-commentaries. And I respect Leyner’s efforts to push the boundaries of fiction beyond plot and character. But when attempts to completely reconfigure our idea of the novel don’t wind up working, one starts feeling all the more pained by the absence of the fundamentals of fiction. What makes Leyner’s half-joking admissions of bullshit all the more frustrating are the many moments in The Sugar Frosted Nutsack when he casts his po-mo gamesmanship and exaggeratedly satirical shtick aside, reminding his readers how insightfully and humorously he can write. For example, when Ike lists the things he’d do if he knew he was going to die in a week (“You’d shave every day. You’d keep your shoelaces nice and snug. You’d work on your posture”), or when a recitation attendee describes asking a Christian therapist who “cures” gay people to deliver his incantation backward so he might become gay like his favorite songwriters, Leyner hits a perfect note between snark and sentimentality.

Nowhere is this balance better struck than in a scene between Ike and his wife, Ruthie. Ike’s written her an elegant list of everything he knows about women, and when she finds out he plagiarized the whole thing from O, The Oprah Magazine, she remains in love with him “not at all in spite of what he’d done, but, in large part, because of it — here was a man willing to steal for her.” It’s a lovely flash of sympathetic character. And then, in an all too typical Leyner move, the passage ends with this: “Ninety-seven percent of people think that it was SUPER-SEXY of Ike to totally plagiarize that from O, The Oprah Magazine!” Consider me, alas, in the minority.

This post may contain affiliate links.