I’ve never read Isaiah Berlin’s famous essay “The Hedgehog and the Fox,” but I’ve seen it referenced to the point that I don’t feel much guilt in citing it for purposes both mercenary and rhetorical. Taken from a quote by the poet Archilochus (“The fox knows many things but the hedgehog knows one big thing”), the title refers to a distinction Berlin draws among thinkers: the hedgehogs, who interpret the world through a singular idea, and the foxes, whose views are informed by a wide, various range of experience.

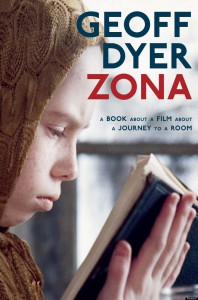

Or something like that. Again, I’ve never read Berlin. My point here is simply that Geoff Dyer’s new book Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room is a fox despite seeming like a hedgehog, and it probably shouldn’t be taken much further than that. Now if you’re familiar with Dyer’s work and didn’t start skimming this review the moment I ignored a whole host of metrics (exactitude, nuance, historicity, etc.) and began ascribing anthropomorphic qualities to books, you’re probably nodding your generous head at this point.

Dyer has built his reputation writing books and essays that are intellectually expansive and rambling; they tend to flit from subject to subject and in the process cover a lot of surprising ground. The New Yorker once said of Dyer, “If [he] weren’t so prolific, it would be tempting to crown him Slacker Laureate. A restless polymath and an irresistibly funny storyteller, he is adept at fiction, essay, and reportage, but happiest when twisting all three into something entirely his own.”

Although I expected a writing style akin to the just mentioned — a mix of high thought and low puns — I didn’t expect a book as formally aware and graceful as Zona. A little study of a single film, it does so much: steadily expanding to serious heights without becoming ponderous, and constantly digressing without losing focus.

To put it circularly, the book is, as Dyer describes it, a “summary that is the opposite of a summary” of Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 masterpiece Stalker. “Long…synonymous with high art and a test of the viewer’s ability to appreciate it as such,” the film follows a three-man expedition into a mysterious, perhaps irradiated, probably sentient area known as the Zone. Led by a man referred to only as Stalker, the party is in search of the Room, an area of the Zone rumored to fulfill one’s deepest desire.

Dyer first saw the film when it was released and its effect on him was profound. In one of my favorite examples of forthright praise, Dyer remarks that “if I had not seen Stalker in my early twenties my responsiveness to the world would have been radically diminished.” The film, it seems, couldn’t be more important to him. The central current of the book exudes this attention and urgency.

Zona includes a detailed description of each of the 142 shots that make up Stalker. On another level (or on a series of questionably, gloriously related levels), Zona is an explosion and a disarticulation of a challenging work of art, “an account of watchings, rememberings, misrememberings, and forgettings.” It is a hedgehog that is the opposite of a hedgehog — a fox. Zona is always and absolutely about Stalker, but it is also about everything a work of art can come to mean when it moves us. Dyer’s many digressions, recorded liberally in footnotes and extensive asides, are all attempts to describe a relationship to a single piece of art in something approaching fullness. Zona seeks to account for the variety of ways we can respond to a film and the strange corners of our lives that it heightens and illuminates.

Zona is a small book that contains multitudes. Over its course, Dyer provides a sentimental account of his life as a cinephile; thoughts on faith, heaven, LSD, and threesomes; beautiful ephemera related to the production of Stalker; and a steadily evolving interpretation of the film under inspection. And all of this happens seamlessly as Dyer’s prose glides along, unencumbered despite its heady subject matter and gangly list of interests.

One of the big questions posed by Zona, and by extension by its hybrid style, is existential: “Whether it will amount to anything — whether it will add up to a worthwhile commentary, and whether this commentary might also become a work of art in its own right.”

In answer to his own question, Dyer writes:

If mankind was put on this earth to create works of art, then other people were put on earth to comment on those works, to say what they think of them. Not to judge them objectively or critically assess these works but to articulate their feelings about them with as much precision as possible, without seeking to disguise the vagaries of their nature, their lapses of taste and the contingency of their own experience, even if those feelings are of confusion, uncertainty or — in this case — undiminished wonder.

That seems about the size of it. Dyer writes at one point (or several, I’m not sure which) that in Tarkovsky’s cinema the meaning is in the movement of the camera, that there is no separation of visual style and thematic content, and that to mention the unity of visual style and thematic content would be misleading precisely because it requires that conjunction ‘and.’

The same is true of Zona. The unspooling of interests and impressions and realizations and jokes is an attempt to depict a response to art, the effect of which is art itself.

This post may contain affiliate links.