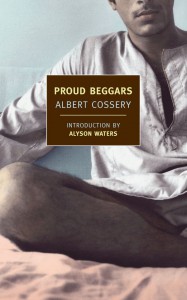

[New York Review Books; 2011]

Tr. from French by Thomas Cushing

By Helen Stuhr-Rommereim

Maybe the reason Albert Cossery’s work has never received much attention, particularly in English, was that the author himself never paid much attention to writing, or to work of any kind. When he moved to Paris permanently in 1945 from his native city of Cairo, he checked into a hotel room on the Left Bank and stayed there for the rest of his life. He spent his days sleeping until noon and strolling about, or sitting in cafes with Jean Genet, Albert Camus, and Jean-Paul Sartre. In an interview with Banipal from the last years of his life, Cossery said “I write when I have nothing better to do, or in other words when I am bored.” Proud Beggars is often spoken of as the masterpiece of Cossery’s eight-novel oeuvre, but since 1981 it has been out of print in English. Now it is being published again, thirty years later, with a new translation.

Cossery’s haphazard lifestyle and writing routine were purposefully so. He was a sort of philosopher of laziness, and his life and work show that such a philosophy should not be dismissed. His laziness was a radical rejection of everything modern existence is generally supposed to be about (producing, consuming, achieving, etc.), and his belief that one must exist outside society to lead a peaceful and thoughtful life forms the core of many of his novels, including Proud Beggars.

Set in Cossery’s native Cairo, as are nearly all of the books that he wrote, Proud Beggars opens with protagonist Gohar awaking in his pile-of-newspapers bed to find his room has been flooded with water escaped from the neighboring apartment, where wailing women in mourning are cleaning a dead relative. It’s a harrowing scene: Gohar, a cold, penniless beggar, is awoken yearning for hashish and with no money to buy it, dripping in the water of death.

But Gohar is not just a poor soul that fate forgot. He chose to sleep on newspapers and live with nothing. We find out later that he left a position as a university professor in favor of the freedom of idleness and poverty. Cossery describes Gohar’s relationship with material things:

“He hated to surround himself with objects: objects concealed hidden germs of misery—the worst kind of all, unconscious misery, which fatally breeds suffering by its unending presence.”

Gohar is also addicted to hashish, and when he leaves his death-washed room he goes off to the whorehouse where he works occasionally as an accountant to search for his best friend, pupil, and drug dealer Yeghen. Instead he finds himself strangling a beautiful young prostitute in a fiending haze.

The rest of the novel follows Gohar, Yeghen, and their idealistic young friend El Kordi, the titular proud beggars, as they interact with police inspector Nour El Dine, a miserable closeted homosexual whose time with these poor philosophers gradually shakes his belief in the law and finds him yearning for the kind of peace to be found in destitution. Nour El Dine is the one character who has chosen to play by the rules, and he suffers for it. Cossery’s universe is governed by a system so stacked against humanity that the only way to find peace is to exist in the margins, outside of social norms and worldly obligations. Proud Beggars is not a glorification of poverty, but a condemnation of society as it exists.

Though the novel ostensibly revolves around Gohar’s murder of the prostitute, as Proud Beggars progresses this act gradually fades into the background and the moral and legal culpability of the murderer also becomes unimportant. The story takes place in the quiet spaces between plot points, in the various conversations and inner monologues of the characters, who discuss the absurdity of poverty and the world’s unending injustice. The fact of the murder hovers uncomfortably around the edges of the narrative.

Cossery told Banipal, “I have a special regard and fondness for my characters, they are moving and rare.” That deep and apparent affection enlivens Proud Beggars. Nour El Dine is as tragic as he is pathetic, and Gohar, Yeghen, and El Kordi are selfless, loving, and idealistic. At the same time they are obviously and profoundly flawed—Gohar is a murderer. The contradictions of the three friends’ behavior leave a wide berth of ambiguity around Cossery’s ideas.

Though it plays out amid a host of tragedies, Proud Beggars is funny, and despite frequent philosophizing it is written with a lightness which perhaps reflects Cossery’s unencumbered writing process. Cossery’s work faded into the margins of literary history as he himself slipped by in the margins of society. But Proud Beggars is a fine and fascinating novel and it is also a joy to read.

This post may contain affiliate links.