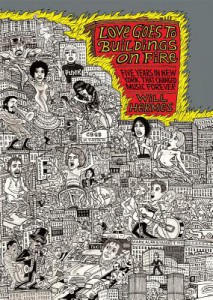

“Sometimes the worst situations produce the deepest beauty, the most profound change,” writes Will Hermes in the prologue of Love Goes to Buildings on Fire: Five Years in New York That Changed Music Forever. It’s not an original sentiment by a long shot, but it’s certainly applicable here. New York from 1973 to 1977 – Hermes’ time frame – was as musically fertile as it was morally and financially decrepit. The streets were literally filled with garbage, President Ford had to issue an 11th-hour bailout before the city went bankrupt, unemployment was escalating at a fever pitch and violent crime was ravaging the city. The seventies were swimming in the wake of the sixties, and had to answer to the mistakes of the hippie generation. For Hermes, this is the backdrop for the music scenes he covers: punk, hip-hop, disco, jazz, classical, salsa, and whatever happens when those distinctions become blurry. Love Goes to Buildings on Fire is first and foremost a painstakingly thorough panorama, a rock and roll-veritè Garden of Earthly Delights.

New York itself is every bit as interesting as the music Hermes discusses. It’s old, it’s huge, and it is a perennial hub for music. It’s also volatile and mercurial, which makes it a compelling character in Hermes’ narrative. Hermes traces the lineage of each venue, each apartment house, and each musician in painstaking detail. In doing so, he paints a portrait of a city that musicians take upon themselves to reclaim over and over again. The seventies is yet another chapter in this saga. It only half works, though: often times, Hermes indulges the record-store tendency to namedrop. As a result, Loveoften feels like a laundry list. It also means that Hermes devotes less time to comment on what it is he’s showing us, or to contextualizing the music into a more national picture. Hermes’ New York is an island — more so than in real life. The scenes in New York all have ties to those in San Francisco, Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, and Havana, all of which he refers to little more than in passing. It implies that musicians moved to New York to leave their old homes behind, when in fact what happened was more of an urban exchange than defection.Love works best when Hermes makes clear the link between the nascent music scenes and life in the city. This was a choice that plenty of artists made — to make music that was unmistakably New York. Take salsa, for example: it was effectively a creole, much like what became jazz in New Orleans during the 19th and early 20th centuries. New York was the arena in which it came together, a polyglot musical language taking bits of Cuban music, Puerto Rican music, and the blues (among other things). It couldn’t have come together anywhere else, at least not in the states.

Hip hop was also a creole of sorts, but Hermes is a little more specific about its utility. The hip hop scene is most unique here because artists weren’t interested in commercial success: instead, hip hop was peacekeeping music. Kool Herc, Afrika Baambaata, Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five all played a little bit of everything – Cuban music, Puerto Rican music, American funk — to get people of all races and nationalities to stop fighting and start dancing. Hip hop caught on and became commercial since all these artists happened to be innovators, and since it was danceable.

Hermes pays due lip service to punk rock, but he does little more than chronicle the scene. It’s unfortunate, because punk rock’s self-contradictory nature is one of the great mysteries of pop music. Musically, punk draws on what was becoming traditional pop music – Phil Spector groups, blues – but could go as far as announcing itself as ahistorical. Punk was made by misfits, but the scene hypocritically fostered exclusion. Hermes never addresses the question of whether or not NYC punk’s solipsism was galvanizing, or just a whole lot of fiddling while the city burned. It’s an important question for anyone thinking about rock music critically, especially people who call themselves punks. By limiting his scope to New York ’73-’77 Hermes allows himself to shirk a discussion of punk’s paradoxical relationships to commodity, but punk’s isolationism should be reckoned with regardless.

If the seventies were a decade in search of an identity, Hermes doesn’t make much of a case for it actually finding one through music. Though he details several different music scenes, they hardly intersect. Session players would seamlessly move between genres and play on all kinds of albums, but those players were relatively few and far between. Hip hop was sample-based, so live musicians weren’t necessary. Punk rock musicians had limited musical skills, if they had any at all, and session players still have a hard time with the punk idiom. Punk’s politics (if they existed) also could be alienating: the Dictators were homophobes, and in 2002 Johnny Ramone ended his Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Speech with “God bless President Bush.” The scenes didn’t cohere, so the ties that bind Hermes’ narrative together are flimsy at best. That the music scenes in the ’70s were so bifurcated is a point of interest, albeit one that doesn’t get much ink.

Though Hermes gives a thorough account of the actual music and an exposition of what led to the particular moment that he covers, he makes short shrift of how this music changed the world. Tracing the genealogy of bands is an easy exercise, once you’ve listened to enough music. The sound is important, but it’s only part of the story: the seventies was a period of musical liberation and iconoclasm, and that spirit lives on. Punk was easy, it was cheap, and it was catchy; so it spread, and punk scenes still abound all over the world. The jazz and classical music from this time opened up the idea of what music could be: it wasn’t freedom from tonality or tradition, but freedom to pick and chose what elements of the past to jettison, and what of the future to invent. Hip hop’s narrative after the ’70s may be the most compelling for all the directions it took both politically and musically. It’s clear that Hermes knows his shit, but he does the reader a disservice by stopping himself short: apart from the occasional “I was there,” Hermes keeps himself out of it. It gives Love a faceless quality, as Hermes melts into the sea of names and places that make up his monolithic New York.

This post may contain affiliate links.