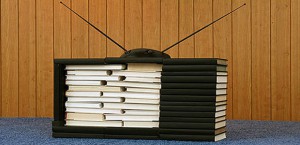

Last week Julie Bartz discussed the recent wave of novelists (Rushdie, Franzen, Russell) writing or adapting work for television. She touched on a significant trend (Jennifer Egan, Chad Harbach, and Sam Lipsyte are also developing HBO projects) and expressed concern that novelists are “now trying to take part in (or take over) a medium they once felt symbolically rejected by.” Rather than share Julie’s uneasiness about novelists gravitating toward television, however, I’m thrilled to see television gravitating toward novels in a more overt and potentially innovative way than it already has been.

Last week Julie Bartz discussed the recent wave of novelists (Rushdie, Franzen, Russell) writing or adapting work for television. She touched on a significant trend (Jennifer Egan, Chad Harbach, and Sam Lipsyte are also developing HBO projects) and expressed concern that novelists are “now trying to take part in (or take over) a medium they once felt symbolically rejected by.” Rather than share Julie’s uneasiness about novelists gravitating toward television, however, I’m thrilled to see television gravitating toward novels in a more overt and potentially innovative way than it already has been.

In 2006, David Simon confessed his initial apprehension about asking novelist Richard Price to pen episodes for The Wire. “We really thought it was presumptuous,” he said, asking Price to work in “a medium that’s been stained by a lot of mediocrity.” By assembling Price, George Pelecanos, and Dennis Lehane, Simon rose eons above mediocrity, crafting art that critics compare with the 19th century novel more frequently than other TV. Numerous works (The Sopranos before The Wire, Deadwood, Mad Men, and Breaking Bad after) have imbued TV with novelistic integrity, rededicating a small but significant segment of television storytelling to complex character, slower, assured pacing, and narratives that court active viewers over passive channel flippers.

The forthcoming brigade of literature-based series could propel this fusing even further. Julie honed in on Bored to Death creator Jonathan Ames’ lament that novel writing “takes so long,” but omitted an equally telling point Ames makes later: for him, writing his show is like “producing almost a novel every year.” Ames has not abandoned the novel for television; rather, he’s using television to annually craft a novel in a different medium than the page.

HBO’s The Corrections could merge mediums in a different, equally exciting way. “It’s been really fun to dream up all this new material,” Franzen told David Remnick at this year’s The New Yorker Festival, “to work out what these characters were doing at points in their life that the novel just skated past.” Franzen isn’t funneling familiar elements and arcs from his novel into television, but harnessing television to expand on those elements, to breathe new, supplementary life into his material.

That television so eagerly borrows from contemporary fiction isn’t cause for panic – these shows could redirect viewers to their source material and recruit a whole new legion of readers that their authors might never have wooed. And having recently seen how closely television has borrowed novelistic structure, I’m eager to see what happens when shows start originating from novels themselves. The key word here is borrow – at the end of the day, books and television, like books and film, are two totally independent forms. In a 2008 Charlie Rose interview, while answering a question about the personal prominence his novels take over his screenwriting work, Price nodded at a hardcover copy of his most recent book in Rose’s hands and insisted, “It’s who I am.”

This post may contain affiliate links.