by Emma Schneider

Encompassing fifty years, The White Woman on the Green Bicycle introduces readers to the birth and early development of independence in Trinidad through the life story of an expatriate couple who arrived as colonialism left. Herself a native of Trinidad and the daughter of two such expats, author Monique Roffey’s interaction with the world of her novel is deeply familiar and cognizant of the intricacies of Trinidadian society, at least as far as these nuances are available to a white woman.

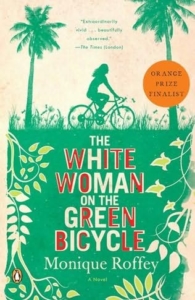

Having only intended to stay in Trinidad for her husband’s initial three-year contract, Sabine never fully accepts her long-term status as a privileged resident of the lush, too-warm island. At first she pedals her way around the island, earning a reputation for herself as the beautiful white woman brave (crazy?) enough to bike around Port-of-Spain. But as years pass and skin wrinkles, she retreats to rum and pool chairs, idealizing a lost life on the fog-drenched English heath. Although her husband, George, often returns home smelling of sex, her real competition is with his love for the land. Sabine speaks to the curved hills of the Trinidad as to a fellow woman—one who conquered and stole her husband long ago. She lives without a voice in Trinidad; George acts in blissful denial of her wishes, entrenching himself in his tropical castle rather than boarding the boat back to her comfort, he’s content with his mediocrity.

Perhaps in response to her own powerlessness, Sabine becomes fascinated with the post-colonial political movement in Trinidad. She listens, entranced, to the charismatic political leader Eric Williams. Although she only encounters him a few times, she secretly writes him boxes full of letters over more than a decade. He speaks of a new time when “Massa day done.” Brimming with guilt about her (parasitical?) presence in Trinidad, Sabine cannot help but agree with his message, even as she fears the retribution his powerful lectures may bring.

I was white. White in a country where this was to be implicated, complicated, and, whatever way I tried to square it, guilty. Genocide. Slavery. Indenture. Colonialism—big words which were linked to crimes so hideous no manner of punishment was adequate.

Through Sabine’s obsession and George’s obliviousness, Roffey explores the politics and sentiments of her childhood home. George’s apparent lack of insight into the colonial system he happily perpetuates allows him to believe in his self-worth, while Sabine spends her life racked by the weight of a skewed society she has been obliged to join.

Roffey’s latest novel closely parallels the outline of her own parents’ story. Herself the daughter of an “alpha” British father and multi-lingual Mediterranean mother who immigrated to Trinidad in the 1950s, Roffey creates a frustrated alternate family history. Even one of the most defining objects of the novel—Sabine’s green bicycle—matches a green bike Roffey’s mother also rode around the island in her first years of residence.[1] Roffey uses the sketches of her family to study two opposing sentiments of post-colonial white residents: lingering greed and guilt. Although the feelings are made more available by separating them between husband and wife, such an emotional simplification caricatures humanity. Roffey’s novel also hearkens to Gatsby in George’s enthusiastic reinvention of himself (and love for the pool), though with traces of colonialism funding his parties and the love of a curvaceous landscape consuming his passion.

While Roffey disappoints in character complexity, she excels in the rhythms of language. Dialogue floods her pages. She swims effortlessly between a range of dialects that accentuate the individuality, the separation, and the heritage of her characters. Not only do her characters interact closely with each other, they seek out conversation with themselves, with absent others, and with the natural world. The White Woman on the Green Bicycle expresses the diversity of a culture through the variety of its voices. If nothing else, Roffey’s book speaks.

[1] http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2010/may/08/monique-roffey-trinidad-parents-marriage

This post may contain affiliate links.