By: John Farley

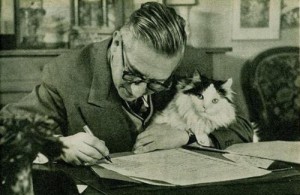

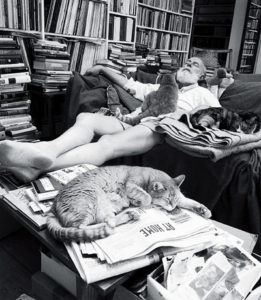

Approximately sixty descendants of Ernest Hemingway’s polydactyl clowder still haunt the grounds of his Key West cabana. Williams S. Burroughs wrote, “My relationship with my cats has saved me from a deadly, pervasive ignorance,” and a 1997 photograph shows a deathbed-ridden Burroughs receiving some kind of obscure last rites from an apple-coated companion. And beyond the hundreds of intimate pictures of the twentieth century’s significant literary figures in the arms of tabbies and toms, the annals of world poetry, fiction, and essay are lined with vast expanses of feline characters and symbolism, wildly disproportionate to that of dogs. Colette, Twain, Plath, Sagan, Chandler, Shaw, Bradbury: all cat lovers and writers on the subject of cats. There are too many others to name here, but suffice it to say that writers, second only to spinsters in the throes of dementia, are unequivocally cat people. What, if anything, can be gleaned from this critically neglected relationship? Can a greater understanding of the authorial predilection toward cats illuminate some ingredient in the recipe that makes for a brilliant command of language?

Before theoretically unpacking this litterary box, there are two pragmatic, surface-level observations that help make sense of the writer and cat dynamic. First, cats are far more ergonomically suited to the writing process than dogs. Small, quiet, and lap-sized, the cat is a well-designed pet for someone whose work entails long, solitary periods sitting in a chair. Second, there is a considerable overlap of personality traits in our cat-author Venn Diagram, which produce a fruitful, almost symbiotic system of cohabitation. As a generalization, (good) writers and cats possess a unique curiosity and observational nature, and lead a life largely within their own minds. This makes for a complementary living arrangement that suits both parties’ needs. Both are content to leave one another to their own meditative devices, but the cat is aware when the writer needs to take a break or refill the water bowl, and will react with a casual pass through his roommates’ legs. Unlike the canine’s fickle whimsy and subservience to another’s schedule, cats and writers, even the wildest of their kind, create for themselves highly disciplined routines according to their own complex and unorthodox needs and personality quirks. If the writer works best between the hours of midnight and 6 a.m. then that’s when he will write. If the cat needs to sleep or hunt at odd hours he shall. And through an extraordinary level of patience and focus on the task at hand (writing and hunting for mice, respectively) these two odd creatures generate a new language composed of subtle, yet profoundly communicative gestures and arrive at a rather orphic tier of mutual understanding.

But let’s not kid ourselves, the relationship is not wholly mutually beneficial. In all of these shared characteristics (mysterious, curious, disciplined, creative, self-sufficient) the cat is inarguably superior and could easily do without the writer’s companionship. As noted cat enthusiast Mark Twain noted, “Of all God’s creatures there is only one that cannot be made the slave of the lash. That one is the cat. If man could be crossed with the cat it would improve man, but it would deteriorate the cat.” Perhaps the totalizing similarity is that neither species is a herd animal, both follow the road less traveled, yet Twain’s quote gets it right: cats follow that road better, probably finding some cat-specific entertainment in their fellow’s struggle against the socially normative, probably they observe a lesser being who “really is a little queer/ to leave his fire’s cozy chair.” Frost: also envious of his cat. The cat’s superior weirdness, their ability to open the doors of perception without the crutch of whiskey or opium elevates the cat beyond a compatible pet to a great muse. Poe summed it up nicely, saying, “I wish I could write as mysterious as a cat.”

The notion of cat as muse seems like a good entry point into a deeper diachronic exploration of writing about cats. If the writer sees in the cat some kind of creative ideal, how has this idealization been shaped by the push and pull of civilization? This where things get weird.

When we look at the construction of cat symbolism through history, there’s a really strong opposition between Eastern and Western views of the cat. What unites these opposing views, from the start, is that the meaning-makers were mostly writers, or at least storytellers in some form. Dogs have a pretty stable meaning as helpers, with their ability to act as alarms and aid in the hunt, as far back as 12,000 years. Less practically useful (aside from mouse killing) and trainable than the dog, the cat’s domestic relationship with man begins much later under the reign of Egypt’s second dynasty, around the time the Egyptians borrowed rudimentary Sumerian writing systems and created, for all intents and purposes, the first sophisticated written language. From this point on the cat becomes hugely significant as a religious figure in Egypt, first as the cat goddess Mafdet, and is henceforth positioned as a symbol of justice, wisdom, fertility, and grace. And what’s really interesting about this theological origin is that ancient Egypt’s cats, revered less as pets and more like gods, were almost exclusively in the care of priests, basically the first writers. Even though Egyptian cat worship was banned in 390 AD, the cat as a symbol of good fortune was proliferated throughout Eastern belief systems, most prominently in Japan with the Maneki Neko, or “beckoning cat”, who appears in various legends and as an allusion in several Murakami stories.

Cats become part of a much darker mythology, however, in ancient Greece, where Aesop first notes their inherent deviousness. Things don’t get much better for the cat’s standing in the West after they come under suspicion for causing the Black Death (in retrospect, the decision to pursue mass cat burnings at this time was ill advised, as it lead to an explosion in Europe’s rat population), and by the seventeenth century cats were well known to be in cahoots with witches and Satan. From there on out, cats in European folklore are pretty much exclusively baby killers and witch assistants, or at the very least agents of anxiety and cause for alarm a la Poe’s “The Black Cat.” So, how do we explain this complete inversion of meaning between Eastern and Western views of the cat? It might have something to do with the cat’s independence of spirit being antithetical to Christian value systems. The cat is social outlier. Though it can be domesticated it can never really be trained to serve man. If your culture’s cosmology is conceptualized as a Great Chain of Being, predicated upon a hierarchical structure in which God is served by man and man is served by animals, you might grow suspicious of this one class of creature who doesn’t take man’s shit. You might mistake its preference for the behavioral road less traveled as a sure sign that it’s imbued with a touch of lapsarian evil. The cat’s nine lives taunt the Christian’s single shot at Heaven.

It’s hard to locate an exact date or place, but these dual meanings seem to experience a literary engagement with one another during the Romantic movement in the mid-nineteenth century. At the point where literature gains not just an interest in, but an attraction to the uncanny and libertine, and plots start to entangle elements of the real and the unknown, modern writers begin to identify with the cat. On one hand, this identification is an expression of duality, a developing notion wrought from the early crumbling of European Christianity. On the other hand, cat-like traits become something to revere and aspire to—a fairly new, distinctly romantic notion of the artist as the singular genius whose visions are perhaps endowed by mystic, not wholly benevolent deities. In “Cats,” Baudelaire fancies that “hell well might harness them as horses of the dead,” yet “within their fertile loins a sparkling magic lies.” It’s worth noting Baudelaire’s admiration for the cat’s fertility, as if he’s conjuring the Fertile Crescent.

The nineteenth century’s cat’s abundance of interconnected meanings is sort of an emblematic harbinger for the shape of literature and clichés about writers to come. I’ll stop short of trying to build a wonky Derridean analogy and leave it to Joyce Carol Oates, who sums up the contemporary writer’s interest in cats quite beautifully with, “The writer, like any artist, is inhabited by an unknowable and unpredictable core of being which, by custom, we designate the ‘imagination’ or ‘the unconscious’ (as if naming were equivalent to knowing, let alone controlling), and so in the accessibility of Felis catus we sense the secret, demonic, wholly inaccessible presence of Felis sylvestris. For like calls out to like, across even the abyss of species.”

But where shall cats and authors go from here? I suspect you’re looking at the answer. A considerable machine in the framework of recent political liberation, certainly a purveyor of smut since its advent, and perhaps the future of literary aggregation, the Internet has also become the greatest tool in cat-desiring production the world has ever known. If the future of innovative literature is indeed online, then it seems logical that two paths—the historical relationship between writers and cats, and the web’s odd infatuation with cats—are about to collide, ushering in a yet unattained golden age of kitty literature. What will we make of this bizarre love triangle between author, cat, and Internet? How will we read a cat singularity?

All images via www.writersandkitties.tumblr.com

This post may contain affiliate links.