Full Stop recommends is a new feature with recommendations for reading, listening and watching from Full Stop editors.

The Way We Live Now, by Anthony Trollope. Read by Timothy West. BBC WW, 2009.

The Way We Live Now, directed by David Yates, 2001

Over three and a half months this winter and spring I listened to Anthony Trollope’s Victorian satire The Way We Live Now read by the English actor Timothy West, on the recommendation of my mother, a tireless reader of sprawling nineteenth century novels and fervent advocate of the audio book. That wry, sly voice (Trollope’s layered with West’s) and its uncompromising realism has been the best possible companion in escapism. Though it’s an unsettling kind of escapism, since the novel has as much to say about the way we really do live now as about the way those Brits lived then. Capitalism is Trollope’s great subject, and he brilliantly shows the way it governs and corrupts not just the economic and political life of a city but its social order, infecting money and government, love and courtship, property and inheritance.

At the center of the novel is Augustus Melmotte, the tyrannical investor, who cuts a swath through London society with his bold effort to fund the creation of the Mexican and South Pacific Railway. Melmotte is essentially running a Ponzi scheme, and the novel is less about the presence of money than its invisibility. Trollope’s rake is the penniless baronet Sir Felix Carbury. He pursues Melmotte’s daughter Marie, a heiress of fantastic wealth who adores him and is desperate to be adored, but he prefers the feisty country girl Ruby Ruggles who runs away from her grandfather and her fiancé believing Felix will marry her. Felix is a villain but he’s also a pawn, improbably stupid and grasping at straws—as with Dickens’ young villains, Felix is vacant inside and thus can enjoy only a vacant hedonism.

In The Way We Live Now, everyone is an equal candidate for both sympathy and satire, and Trollope doles these out in equal measure. The most righteous character, Sir Roger Carbury of Carbury Hall, around whose estate a drama of inheritance plays out, is by extension the most intractable and emotionally cloistered—even the characters who admire his courtly bearing and irreproachable moral standard cannot bring themselves to live up to it. I far prefer to him the delicious wickedness of Lady Miranda Carbury, who writes the historical potboiler Criminal Queens and favors her ruinous son over her virtuous daughter, or the gun-slinging self-reliance of the American widow Mrs. Hurtle who crosses the Atlantic to try to win back her ex-lover, sweet, moral Paul Montague, or the simpering naïveté of Marie Melmotte. Perhaps at the root of my affection is the way the novel’s magnificent tonal shift—from satire to melodrama—hinges on these characters. They are not necessarily reformed, but they are rebuked and humbled, and they deepen in surprising ways. (Marie Melmotte does not remain gullible for long; hers is the most dramatic, and the most affecting, transformation.)

As a coda, I recommend the 2001 BBC miniseries of The Way We Live Now, directed by David Yates (who directed the last three Harry Potter films), and starring David Suchet as Melmotte, Matthew Macfayden as Sir Felix, and, in the best imaginable casting, the marvelous Shirley Henderson as Marie Melmotte. Miranda Otto (The Return of the King) plays an extremely sexy Mrs. Hurtle—she saunters, drawls and schemes, presiding over her dim boarding house lodgings like a spider spinning her web. Yates’ projection of contemporary sexuality onto the Victorian narrative doesn’t always work, but he does grant Felix a small reprieve at the end—the last scene signals the persistence of mischief. It’s a device I imagine Trollope would have liked.

–Amanda Shubert

* * *

l’hote, by Freddie de Boer

I began reading Freddie de Boer’s blog l’hote a little over a year ago as a result of Andrew Sullivan et al’s frequent links, responses, and clear, abounding respect. Freddie is a graduate student and, perhaps unsurprisingly, a great deal of his best work concerns higher education. His positions are often provocative (see, for instance, his writing on grade inflation), but they’re never cynical or opportunistic. Freddie’s a first-rate writer, thinker, and skeptic, and his essays are notable for not only their quality, but for their author’s keen awareness of his own presuppositions: they are completely devoid of any “us vs. them” shorthand or rhetoric, which I am particularly grateful for.

I wonder, often, if there has been a period of greater intellectual arrogance than the one I live in. Of course there has been; there was a time before the modern critique, and, you know, Aristotle had already figured it all out. But it’s hard to keep that perspective in our current time. I have watched, with half-horror and half-bemusement, the rise of what I call we might call human achievement yuppies. They are all over: the techno-utopians, the market fetishists, the hipster teleologists, the neo-Aristotelians, “the Secret” devotees and similar cultists, the prosperity gospel evangelists, the proponents of various self-help books, the lifehackers, the starry-eyed socialists, the evolutionary optimists, the scientism proselytizers, the policy wonks, the personal virtue republicans…. Incidentally, were I in charge, I would hold the TED conferences or similar in a Brazilian favela, or village in Haiti or Somalia. I don’t think you can meaningfully come to understand human progress without understanding the depths of human misery; a consideration of the human endeavor that weighs only the progress and none of those who have been progressed upon is a work of fantasy. …. I find the constant invective against the postmodern turn in the academy so strange. Postmodernism is not and has never been a powerful force in the world; for how could it stand against the dueling certainties and totalizing ideologies that we have never fallen out of love with? For my part, personally, I distrust those that think of practicality as a cardinal virtue, who believe our experience represents finally a series of problems to be solved, who think that efficiency is to be pursued in all elements of human achievement, who think that living is something that can be done better or worse. I’ll favor those who take as their goals to be beautiful, to be moral, and to be happy. There is no greater insult in this than the expression of personal preference. Such things are personal, and if you’ll forgive me, unspeakable.

* * *

“The Balloon” by Donald Barthelme

I first read Donald Barthelme’s “The Balloon” in February of this year, after persistent needling from a good friend who, having taken my measure, declared the author “right up my alley.” I’d heard of Barthelme before, but never read him, and so was able to bask in that rare readerly joy that accompanies an unexpected – or unprepared for – discovery of some brilliant writer. I’m not sure if “The Balloon” was the first of the man’s stories I read, but it’s without question one of my favorites and more often than not, the one I recommend when the messianic urge moves me.

It begins gently and matter-of-fact: “The balloon, beginning at a point on Fourteenth Street, the exact location of which I cannot reveal, expanded northward all one night, while people were sleeping, until it reached the Park.” The narrator then goes on to describe the strange balloon’s gradual, inexplicable expansion throughout and above a large section of Manhattan and the various responses occasioned by its unannounced appearance.

Up until the final paragraph there is no hint of a plot; as the narrator states early on: “it is wrong to speak of “situations,” implying sets of circumstances leading to some resolution, some escape of tension; there were no situations, simply the balloon hanging there – muted heavy grays and browns for the most part, contrasting with walnut and soft yellows.” Likewise, the thrill of reading “The Balloon” is not at all related to meaning or resolution, but rather the experience of Barthelme’s exuberant, freewheeling, wacko prose. As David Gates writes in the introduction to Barthelme’s Sixty Stories collection, the man does not write “stories of W doing X to Y with the result of Z, but stories of what goes on in a vast, various and noisy consciousness.”

“The Balloon” is commonly interpreted as a sort of sly, self-exegesis of Barthelme’s attitude toward writing fiction, wherein his art is presented as a big strange beautiful thing without intrinsic meaning or definition but capable, nevertheless, of eliciting meaningful subjective responses, and to my mind, that’s a perfectly serviceable interpretation without much hooey. But it’s not really the reason I love the story, or why I press it, sweaty palmed, on anyone I think would appreciate it. I love this story because it performs what it describes so gracefully, and with such humor that every time I reread its six-pages, I gape at the words like one of the stunned Manhattanites. It’s tempting to pepper this short recommendation with passages from “The Balloon,” and even out of context they would be stunners, but its best read wholly, and in one go, and if possible out loud.

–Jesse Montgomery

* * *

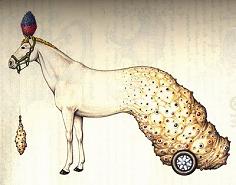

Codex Seraphinianus, by Luigi Serafini

Last month, I returned to Oberlin College to visit my freshman year roommate, Dave, who surprised me with an appointment at the art library to view a copy of the Codex Seraphinianus, an artist’s book created by Italian designer Luigi Serafini in the late seventies. This 360-page oddity is modeled after an encyclopedia, but its strange script and grotesque images seem to come from a distant world, with its own algebra and fire, or perhaps from a not-too-distant future in which genetic engineering is a hobby and LSD is available over-the-counter.

I’d sent Dave a PDF of the Codex months before, and though we’d both seen every page more than once on our computers, we felt like children as we approached the art librarian, who immediately instructed us to hang up our coats and wash our hands. “We just washed our hands!” we wanted to plead. But that line never works. When we returned to the desk, having backed through several doors with our sterilized hands out in front of our chests like surgeons, the librarian was gone. We imagined her descending into the bowels of the building to remove the codex from its resting place while we thumbed through books, rearranged the mobile stacks, and called to one another, in our loudest whispers, when we found nudes or other images that our limited art backgrounds allowed us to appreciate. Most importantly, we made sure that one of us was always within sight of the desk.

Eventually, we worked up the courage to venture behind the desk and peek into the librarian’s office, and lo and behold, there she was, with the book by her side. She was busy and had forgotten about Dave and me and our extracurricular adventure. But that’s what makes this book so much fun: its vibrant, enigmatic pages evoke the wonder of childhood, of flipping through a dense novel full of big words that might as well be in a foreign language, of skipping to the end of a math book to see the mysterious, Greek formulas that you might one day master, or of marveling at an encyclopedia of a strange world that you’ve only begun to explore.

You can click through an electronic version of the Codex Seraphinianus at the Internet Archive, here, but the physical book, with its vivid ink and handmade ivory pages, is worth washing your hands twice to hold.

–Eric Jett

This post may contain affiliate links.