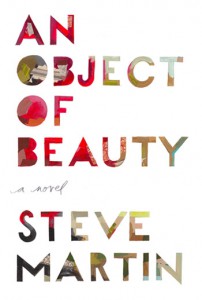

[Grand Central; 2010]

by Abbe Schriber

“If a picture had been on the market recently without a sale, she knew it would be less desirable. A deserted painting scared buyers. Why did no one want it?…When Lacey began these computations, her toe crossed ground from which it is difficult to return: she started converting objects of beauty into objects of value.”

What I can’t decide about An Object of Beauty is what it can’t seem to decide about itself—its ontological destiny. Is the book a character study of its young protagonist, Lacy Yeager? Is it attempting to be an “exposé” on the for-profit sector of the art world? Or, perhaps,is it a commentary on the ways in which our culture ascribes aesthetic and monetary value to art objects? The actor/writer Steve Martin’s third novel, An Object of Beauty is his second to revolve around a young woman and the themes of money and consumerism, the first being his 2000 novella Shopgirl. While Lacey is far different—charismatic, fiercely ambitious, and much of the time utterly loathsome—than Mirabelle, the central character in Shopgirl, there are similar gaps in the women’s characters. Both are awkwardly characterized, more Martin’s filtered, flattened idea of a woman than a believable, emotionally-complex person. Both Lacey and Mirabelle seem content to find solace in sex, money, and status in their respective worlds.

Yet both also attempt to find their way in undoubtedly male-dominated worlds, and this is merely one aspect of the New York art world that Martin rightly and so aptly captures in An Object of Beauty. Lacey works her way from “the spice rack of girls” at Sotheby’s (where she catalogues and attributes paintings to artists in her first job, one of many embellished, laughably implausible scenarios in her career’s trajectory); to ultimately opening her own Chelsea gallery, along the way becoming a savvy connoisseur, businesswoman, art collector and seductress. Lacey’s story is narrated in retrospect by her friend and one-time fling Daniel Franks—an equally repellent character if only because of his complete lack of personality—who opts for a “less glamorous” life as a writer and art critic, yet is in perpetual, wide-eyed awe of Lacey’s antics. Lacey is a hard worker, but subsequently manipulates, lies, and breaks the law in order to get what she wants, as the novel escalates into a thriller based on the fate of a Maxfield Parrish painting belonging to Lacey’s family, with several banal love story subplots along the way.

The strength of Martin’s book is its perceptive, sharp-witted, and at times deeply dark observation of the for-profit side of the New York art world. It’s clear that this was what Martin was really setting out to accomplish, but what is murkier is how he feels about it. The ambiguity in his descriptions could be seen as both celebration and critique—Martin is an equally admiring, wry, and self-aware observer, rattling off lines such as: “…he did like that the Pace Gallery had hung an Agnes Martin opposite a Robert Ryman so that they were ‘in dialogue’ with each other. ‘In dialogue’ was a new phrase that art writers could no longer live without. It meant that hanging two works next to or opposite each other produced a third thing, a dialogue, and that we were now all the better for it.”

Drawing on his passion for art of all kinds—the book is littered with carefully chosen full-color reproductions from John Singleton Copley to Milton Avery to Warhol—as well as his own collecting history, Martin gives scarily exact descriptions of the buzz and tempo that surrounds openings and auctions, the shrewd transactions of dealers, the cruel beauty of Sotheby’s employees, and competitive, almost primal drives of collectors. The book, more interestingly, also serves as a rudimentary primer to the shifting landscape of the contemporary art world in New York, from the early 1990s up through 9/11 and the economic recessions of the last several years. It is a history and vocabulary that can be dizzying to the outside observer, but Martin proves a keen guide, and his strength is in weaving this larger context into the body of the narrative. However, by focusing the novel more specifically on the auction house/dealer/gallery aspects of the art world, and rarely addressing museums, non-profits, exhibition spaces, or other integral components of the larger art community, this book is not really about the art itself, nor is it a full picture of the larger art world—and it is certainly not about the plot and characters that Martin awkwardly, even half-heartedly, advances. More so, it is about the ways in which the market, and really everyone who works with art for a living (even us lowly, Daniel Frank-esque writers), is complicit in the valuation, increasing professionalization, and even fetishization of art in current times. The equation of art + money + sex is a potent one in An Object of Beauty, and the lesson here seems to be that Lacey, sadly, believes the sum of these parts—power—is what matters. If only this book had convinced me that Steve Martin feels any differently.

This post may contain affiliate links.