by Alex Shephard

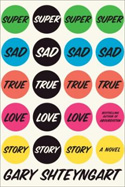

Set somewhere in what is ominously and lazily referred to as the not-too-distant-future — which, of course, means that its true subject is the present — Super Sad True Love Story tracks the romance between Lenny Abramov and Eunice Park. The former is a middle-aged, balding depressive who is likely the last person on Earth who still owns, and for that matter reads, books. The latter is a 24-four-year-old recent graduate of Elderbird College (with a major in Images and a minor in Assertiveness), who is remarkably cute, often cruel, and ultimately sympathetic. Both are the children of immigrants, desperate to fulfill their parents’ expectations and desperate to overcome the insecurities that are the scars of their upbringing.

While Lenny and Eunice fall in and out of love, it’s the last days of Rome in America: everyone is fiddling. Shteyngart’s vision of America is chilling and hilarious, often at the same time—it is a pitch-perfect satire and grotesque exaggeration of our obsession with technology as well as just about everything that’s currently going wrong in America. The debt crisis is so dire that dollars are yuan-pegged and the American economy is wholly dependent on Chinese Central Banker Li; the military is stuck in a costly war (in Venezuela) and its mistreated veterans appear to be readying for civil war. Books make cameos outside of Lenny’s apartment, but they are always rotting, forgotten in a corner. Most striking and effective is the äppärät, a descendant of the iPhone that takes everyone’s personal information – their credit score, for instance, and what others, especially strangers, think of their looks and personality – and makes it very, very public. One’s hotness rating obviously trumps one’s credit rating: despite the debt crisis everyone is shopping, shopping, shopping (on credit, of course)

The shit, as I’m sure you’ve guessed, hits the proverbial fan. America descends further and further into Third World despotism and poverty while Lenny and Eunice – their relationship chronicled through Lenny’s diary and Eunice’s acronym-riddled emails in what can only be called a postmodern epistolary – are pushed together and pulled apart by the crisis.

Shteyngart understands the irresistible appeal of social networking—when the äppäräts stop working, one teenager’s suicide note explains that he “‘reached out to life,’ but found there only ‘walls and thoughts and faces,’ which weren’t enough. He needed to be ranked, to know his place in the world. And this may sound ridiculous, but I can understand him…my hands are itching for connection.” And yet, Shteyngart also shows that connection to be too often superficial: while we are able to communicate with and rank others with greater and greater precision and ease, we lose our ability to communicate ourselves with precision and empathy. Language is replaced with statistics, memes, abbreviation.

In this sense, Shteyngart is an heir to Vonnegut, a humanist, an expert in the mash-up of the popular and the postmodern, the prophet as Lenny Bruce, riffing in the wilderness of the digital age, a writer of what Martin Amis (referring to Vonnegut’s Mother Night) called “moral and comic near-perfection.” And, of “young” American novelists, Shteyngart is Saul Bellow’s closest relative: the guardian of both the immigrant novel and the American novel, a writer of prose as moving and precise as any currently being written.

After all of this, I am of course unfairly neglecting the book’s most important theme: love. “Things were going to get better,” Lenny writes in his diary. “Someday. For me to fall in love with Eunice Park just as the world fell apart would be a tragedy beyond the Greeks.” Super Sad True Love Story refuses to submit to easy cynicism on the subject of love, or allow it to seem frivolous in comparison to national and geopolitical crises. In this novel, as in life, there is nothing stranger, sadder, truer.

This post may contain affiliate links.