Arno Schmidt is not popular in his home country of Germany because he wrote science fiction. Or at least his writing incorporates enough of the tell tale signs of SciFi that his countrymen have relegated his works to the category of U-Literatur, or Unterhaltungsliteratur. This can be loosely translated as “popular fiction,” with an emphasis on triviality. Germans, notoriously preoccupied with pure vs. unpure, take categorizing their literature into either Unterhaltunglisteratur (low) or Ernste Literatur (high) disturbingly seriously. Raymond Chandler could never have been taught writing classes there, were he a native son. The same would go for Phillip K. Dick, Aldous Huxley, Ursula K. LeGuin, and Stanislaw Lem. Of course, since they’re not German, they’re treated with a cultural gravity that evades science fiction and detective authors born inside of the Fatherland. Too bad for Arno Schmidt. And for us.

Arno Schmidt is not popular in his home country of Germany because he wrote science fiction. Or at least his writing incorporates enough of the tell tale signs of SciFi that his countrymen have relegated his works to the category of U-Literatur, or Unterhaltungsliteratur. This can be loosely translated as “popular fiction,” with an emphasis on triviality. Germans, notoriously preoccupied with pure vs. unpure, take categorizing their literature into either Unterhaltunglisteratur (low) or Ernste Literatur (high) disturbingly seriously. Raymond Chandler could never have been taught writing classes there, were he a native son. The same would go for Phillip K. Dick, Aldous Huxley, Ursula K. LeGuin, and Stanislaw Lem. Of course, since they’re not German, they’re treated with a cultural gravity that evades science fiction and detective authors born inside of the Fatherland. Too bad for Arno Schmidt. And for us.

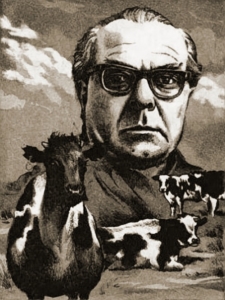

Born to a middle class Hamburg family in 1914, Schmidt worked briefly in a textile factory before being drafted into the Warmacht. He served in a quiet area of Norway until 1945 when he went AWOL in Western Germany in order to be taken prisoner by the British instead of the Russians. He worked as a police translator and freelance writer during a period of listless youth and wandering that came about after the war. He wrote some of the greatest imaginative fiction in modern Germany. Then he died very, very poor.

Why you should care: Gunter Grass is great! No, really, he is! But to give you perspective: Gunter Grass is to Arno Schmidt what John Irving is to Thomas Pynchon. And that’s not to say that the themes are comparable. Schmidt, like Pynchon, was experimental with prose and could create double-helixes of complex self-conscious dialogue with multiple layers of meaning. But Schmidt was more of an individualist — he was a solipsistic pessimist who described his ideal world as the earth after an anthropogenic apocalypse. He was an atheist. But he also maintained that the world was created by a monster named Leviathan that humans could and should overthrow if it ever becomes necessary. I would call him a Gnostic but he lacks the Gnostics’ transcendent grace. The physical world just gets under his skin too much for him to consider its ephemerality .

What you should read: His Radio Dialogs, in which he acts out various authors important to him, are entertaining, but not the meat of his work. That would be the as of yet untranslated to English, 1300 page manuscript, Zettels Traum that you can pick up today on Amazon for only slightly under $500. Based on Finnegan’s Wake, the book takes place at 4 a.m. on a random morning in 1968 when a group of translators get together to discuss the problems of translating Edgar Allen Poe into German. If it sounds boring, you definitely would want to wait for the English edition to be published rather than translating it from the original German yourself. Or you could write a 1300 page book about how hard it is to translate Zettles Traum into English. I think Arno Schmidt would have liked that. In the meantime, you can sustain yourself on his recently translated books of short stories and novellas, which are phantasmagoric and aggressive and surreal. My favorite is “Enthemysis”, in which an Ancient Greek expedition into Africa disintegrates into a fever-dream descent into Weilaghiri, a city pretty much resembling Hell.

So maybe I played up Schmidt’s outsider status a little too much. He did win the Fontane Prize in 1964 and the Goethe Prize in 1973. But for someone who is basically, I think, the German James Joyce, he hasn’t received enough attention from his own people or from ours. I blame Leviathan.

This post may contain affiliate links.