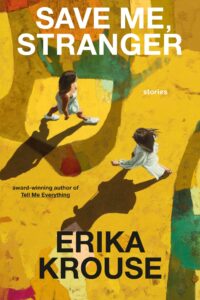

“Save Me, Stranger” could easily be the title of any of the stories in Erika Krouse’s latest collection. The stories feature vastly different settings and characters, but nearly all involve a meeting between strangers in which one attempts to rescue the other from themself or their life. The saving is not always successful, at least not straightforwardly so. In the first story, “The Pole of Cold,” Vera is a woman living in Oymyakon Valley in Siberia, declared the coldest town on Earth. She stays there waiting for her mother, who left with a man from America years before. The weight of her father’s death—run into by a helicopter of rich tourists whose vehicle couldn’t withstand the cold—keeps her there, as well. When Theo, the son of her father’s killers, visits the scene of his own parents’ death, he falls quickly in love with her—“I forgot to mention I’m beautiful,” she say three pages in—and proposes marriage to her as if it is salvation. Vera refuses, perhaps out of a stubborn commitment to her home or perhaps because it was the hope of leaving, not the place itself, from which she needed rescue.

The saving isn’t definitively moral, either: in “Eat My Moose,” two army veterans with cancer find that the disease stops progressing after they perform euthanasia for a fellow veteran. They take this as a sign to continue this service for others. But, for the main character, the ethics are blurry: He tells his friend that they are helping people, but she asks, “Did we, though? Were we right or wrong, how we used our second chances?”

Krouse’s characters are not props for a message; they feel like people, their actions their own. And this made me ache for their success and salvation no matter our differences. I have read many stories full of characters living in apparent fugue states, ruminating more than they act, and it was joyous to watch these characters grab life by the steering wheel, to remember their own agency.

Krouse was born in Yonkers, went to middle and high school in Japan, and now lives in Boulder, Colorado. Her stories’ settings are similarly scattered around the globe. Save Me, Stranger finds characters across states and countries: Siberia, Idaho, Nebraska, Bangkok, Tokyo. Much of the fiction I have read recently has tried to capture “life in the digital age,” which compels writers to set stories in big cities with somewhat shallow characters just there to make a point. Part of Krouse’s appeal, then, is her wildly different characters and settings. Setting is central to this book not just for the reader, as many characters are uprooted or mid-flight from one place to another. They try to find home and find a chance encounter—an unlikely stranger—instead. Home is a slippery thing here. In “Fear Me as You Fear God,” a young woman on the run from her abusive husband longs for “a home that was mine alone, with curtains drawn and the smell of food cooking, comfort, safety,” but then realizes these connotations of a home aren’t real for her: “safety is impossible if you have a home. Snakes find burrows. Caves have no back door…The least safe place in the world is home. It is only safe to be the one crouching in the dark.” This thought process, too, shows Krouse’s skill at carving out a character’s psyche from their experiences.

A book that preaches empathy and human connection is nothing new. But Krouse isn’t preaching, and her characters often don’t understand each other. Some of them, like a girl and her grandmother, find connection over the course of their stories, but most often they save each other despite themselves. Krouse forgets empathy in favor of action. The “savior” in the title story is a kid who takes a bullet for a woman and her daughter who happen to be in the same convenience store. Another woman cancels a date with an anesthesiologist before even leaving her apartment when he is rude to her but takes him in shortly after when he confesses to having neglectfully let a patient die and doesn’t know how to proceed with his life. In both stories, the characters do not become friends, but they care for each other anyway, which is what changes their lives. Krouse seems to believe we are compelled to help each other despite a lack of empathy or connection, and that’s more inspiring than a basic “these people are all people too!” message.

Krouse’s sentences are simple and precise. Her words strike with practiced intention. She builds her stories from nouns and verbs and pares back the adverbs and adjectives in favor of an unexpected simile: “his plastic boots split their tops like two smiles.” She evokes settings just as efficiently, often showing the world acting as much as its characters. In “The Pole of Cold,” she tells the reader about the town by saying, “Birds freeze to death in midflight. Hair sticks to the bed, and eyeglasses fuse to the face. You can hammer a nail with a banana. You can hear a voice outside for over a mile. To find a person, you can follow the trail of breath as it hovers behind.” Her scene-setting is all action and occurrence.

Action begins with attention, which we might call empathy. In the story “The Standing Man” an American in Tokyo obsesses over how the narrator, Satō, memorizes the orders at the ramen restaurant where he works without writing anything down. Satō recounts to the reader how he met the restaurant’s owner: the older man saved him from jumping in front of a train and offered him a job. He describes to the reader that “what [the American] called ‘memory’ is just taking care: paying attention now, and now, and now. Practicing it all day as if your life depends on it, because it does.” After all, he would not be alive if an observant, caring stranger wasn’t paying attention at the train station. Krouse’s writing, and this story in particular, ask the reader not to distract themself from the world around them, to dismiss other people’s lives as “not my problem,” but also to do more than observe: to consider what they might be capable of doing for someone else.

Krouse reminds us that our lives are going to overlap and intersect in ways we do not expect. We are going to bear witness to each others’ miseries, and we don’t have much choice in that. But we can decide whether to intervene, whether to act, whether to break down the walls we think we can construct around ourselves and our own individual lives. At the end of the story “North of Dodge,” Krouse writes, “That’s all the world gives you: chances.”

Erin Evans is a writer from Michigan, now living in New York. She studied Creative Writing and Literature at the University of Michigan, where she also worked as an arts writer and editor for The Michigan Daily. Her essays and criticism have appeared there and in Vestoj.

This post may contain affiliate links.