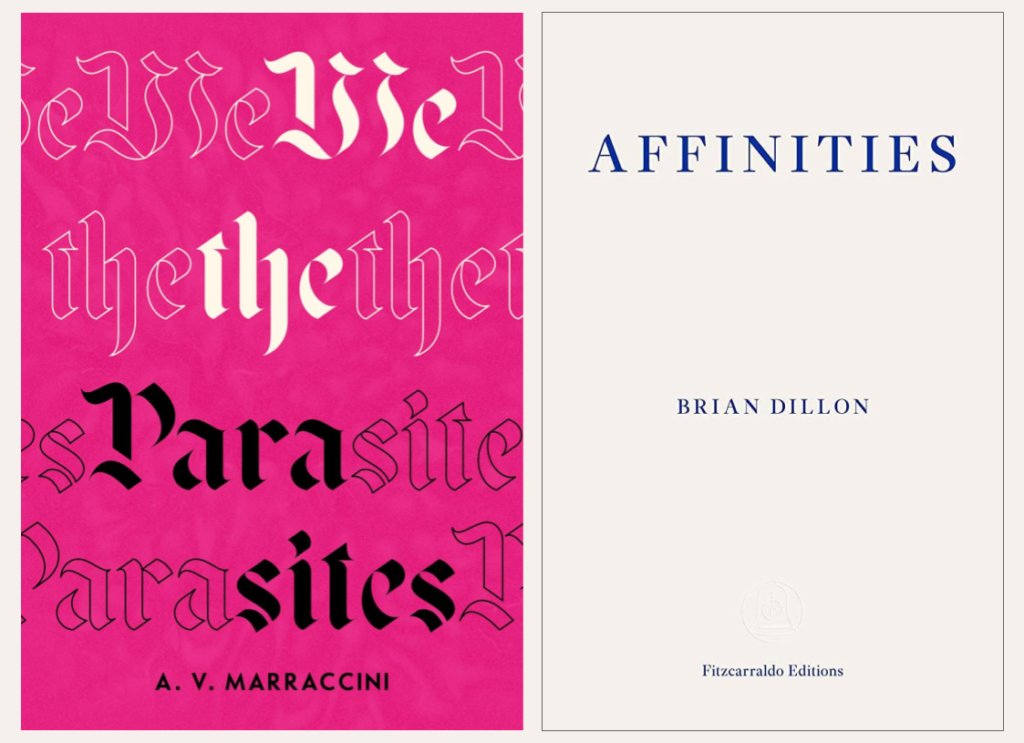

[Fitzcarraldo Editions; 2023]

[Sublunary Editions; 2023]

“I’m no art historian,” Brian Dillon warns in the opening essay of his latest book of criticism, Affinities. A full-time art and literary critic, Dillon nonetheless exposes his own anxieties about the authoritative nature of criticism, recalling a painful moment from early in graduate school when a professor admonished him on the nature of his research: “This was all very well but seemed to consist only of connections.” Dillon’s self-critical voice thus calls attention to the subjective role of the critic: “Are you not simply connecting some things to other things? Do you call this criticism?” Yet Dillon has grown to embrace this organic form: Affinities moves between various artists, forms, and movements with a fluidity inspired by his emotional connection to the images, rather than a desire to situate them within a chronological narrative of art history. This form of criticism instead becomes an innovative way of discovering “affinities” between seemingly disparate artists, threaded together by autobiographical essays and a series of “Essays on Affinity.” In A. V. Marraccini’s We the Parasites, published the same month, the author similarly employs the elegant metaphor of a wasp laying eggs in a fig to meld the personal with the universal, rescuing individual objects from the sea of art history and spotlighting them with a fierce emotional intensity. Although Marraccini is a trained art historian, she too writes for a non-specialist audience, bringing autobiographical experience into play with lengthy meditations on masterpieces of classical antiquity and twentieth-century poets. Together, these books advocate for a new way of inhabiting the works of art we admire and how these personal connections inform and change the art we create in response, recalling Oscar Wilde’s declaration that “criticism is, in its highest development, simply a mood.”

Dillon returns to “affinities” as the center of his criticism, a fluid term he proposes as an alternative to traditional forms of art writing. In doing so, he rejects the notion of objective criticism and hones in on the autobiographical aspects of emotional attachment to art and the minutiae of his artists’ lives. He connects this mode to a long tradition of criticism based on affect or emotion rather than theory: Susan Sontag, for instance, claimed to write essays not to persuade but to produce an effect. In “The Function of Criticism at the Present Time,” Matthew Arnold wrote that the task of the critic was “to see the object as in itself it really is,” to which Walter Pater added: “In aesthetic criticism the first step towards seeing one’s object as it really is, is to know one’s own impression as it really is.” Wilde takes this idea a step further, arguing that the purpose of criticism is “to see the object as in itself it really is not . . . To the critic the work of art is simply a suggestion for a new work of his own, that need not necessarily bear any obvious resemblance to the thing it criticizes.” In this vein, Dillon views a work of art as a jumping off point for his own theories on what draws us to certain objects, one that sparks his meditations on artistic resonances within his own life. A certain photograph or monument might evoke the early deaths of Dillon’s parents, memories of a prayer service in Dublin, a teenage infatuation with Brideshead Revisited, or the renewed resonance of London’s Victorian Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice in the time of COVID-19. In this way, Dillon’s writing could be interpreted as an expansion of the creative-critical essay form that blends autobiography with art or cultural criticism. But it’s perhaps more accurate to say that it follows in the tradition of John Berger’s groundbreaking art critical text Ways of Seeing by demystifying the role of art in contemporary society and promoting the perspective that art holds individual resonances for us all.

In his 2018 book, Essayism, Dillon defines the essay as “unbounded and mobile, a form with ambitions to be unformed.” The same could be said of “affinities,” a multifaceted term that links and structures the text amid Dillon’s many attempts to define it. In the opening essay, he writes:

I found myself frequently using the word affinity, and wondered what I meant by it. An attraction, for sure—to certain works of art or literature, to fragments or details, moods or atmospheres inside of them. To a sentence, for instance, or an essay, but just as easily to an impression diffusing in the mind that could not be traced back to source.

An affinity could be a fascination with a certain artist, writer, musician, filmmaker, or designer, but it also suggests the sense of closeness and shared experience, a spark of understanding or the desire for a creation of one’s own. It is these affinities which prompt us to return again and again to favorite books, movies, music or art, an appreciation which Dillon differentiates from critical interest, “which has its own excitements but remains too often at the level of knowledge, analysis, conclusions, at worst the total boredom of having opinions.” Instead, he is fixated on the way “images and ideas sidled up to each other, seemed to seduce one another, in ways I could not (or did not want to) explain . . . something fleeting,” a philosophy that captures the book’s flitting between different objects, artworks, movements and bite-size artist biographies. Dillon is fascinated by why certain images linger with us, causing him to plumb the double meaning of affinity: both the affinity we feel for certain works and the aesthetic affinities among them.

The result is a dreamy meditation on four centuries of artistic practice, a joyous ramble connected by “Essays on Affinity.” Like Wilde, Dillon seems to believe one of the singular purposes of art is pleasure, and he is fascinated by the often untold stories of subjects who worked on or near the margins. Refreshingly, his canon of mainly twentieth-century artists skews largely avant-garde, female, and LGBT; Hannah Höch, Claude Cahun, Dora Maar, and Diane Arbus, for instance, all worked under the threat of political oppression or in the shadow of more famous male artists. However, there’s barely any mention of Black, Global Majority or non-Western artists, which seems like a critical oversight in an exploration of modern art from the margins—such as a throwaway line about photographer Bill Eggleston, who recalled “that his parents were often absent, so he was effectively brought up by his grandfather and by black servants, some of whom appear in his photographs.” These works are loosely linked through their focus on blurriness or alteration of real-life vision, and his subjects are usually fleeting and vanishing, like affinities themselves. Dillon notes that “a surprising number of the essays seem to be about images that stage in their content or form some act of blurring and becoming . . . a state of bodily between-ness verging on dissolution, aspiring to reconvene otherwise, in alternative forms.” This blurriness manifests in several modes, including the undefined form of the affinity. Dillon is preoccupied by transformations, such as the swirling skirts of the Serpentine Dancer Loie Fuller, the collaging of faces and bodies by Hannah Höch, Dora Maar and John Stezaker, and disguises in the works of Claude Cahun and Francesca Woodman. He views blurriness and imprecision as a distinguishing hallmark of modern art, captured in the blurry self-portraits of Francesca Woodman, the uncanny street photography of Diane Arbus, or the haunting, proto-modernist Victorian photos of Julia Margaret Cameron, whose portrait of her niece Julia features her hair falling in “an unruly fog about her shoulders, where it is hard to tell what is hair, what fabric, and what a more ghostly artifact of the photographic process.”

Marraccini, too, envisions criticism as something generative and unexpected, sparking an individualized creative process within the observer. She asserts the critical gaze as both erotic and queer in its strange, parasitic intimacy between the artist and the viewer. Like Dillon, Marraccini uses a central motif to structure her deconstruction of art criticism, that of a wasp laying eggs in a fig, a metaphor for the parasitic nature of criticism feeding off the creation of another: “But I’m not the fig, I’m the wasp. I burrow into sweet, dark places of fecundity, into novels and paintings and poems and architectures, and I make them my own. I write criticism, I lay it in little translucent eggs.” Asserting that “criticism is a mutualism as parasites like me go, or at least a commensalism, pollinating novels to make more novels,” she ponders the idea that the new creation formed by criticism is also inherently destructive of the original: “The critical gaze is tearing apart, clawing into the soft central flesh of the tree bud.” Rather than a one-sided response to an earlier artist, criticism is reconfigured by Marraccini as a mutual process of creation, one that proves to be both fruitful and self-destructive, a living, evolving collaboration.

Marraccini envisions criticism as an explicitly queer form, one that is “generative outside the two-gendered mode”: “To be a critic and to be queer both are exercises in denial, in misplaced longing, in usurpation of kisses of the mouth.” In doing so, she answers Susan Sontag’s 1964 declaration that “in place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art.” Like many queer teenagers over the centuries, Marraccini identified with the legacy of the Greeks, sleeping with a copy of Homer under her pillow and nicknaming her high school crush the Nike of Samothrace. However, this obsession went further than most: Marraccini wanted to be “more Greek than the Greeks,” to be loved by Homer in the same way she loved it. This mutualistic relationship seemed impossible, compared to a wasp desiring love for a fig, and connected to distance of queer longing, with Marraccini’s love for the seemingly unreachable classmate just as one-sided as her obsession with antiquity. But criticism queers this relationship, allowing the critic to enter into a conversation with the much-beloved artwork.

On a plane, Marraccini thinks of the woman she loves and repeats the W. H. Auden poem “Lullaby” to herself, “as if by saying it Auden was me and was speaking for her, for me, doing what hadn’t been done.” The act allows Marraccini to reach her beloved while at the same time placing herself with a historical canon of queer artists, subverting the structures of form by absorbing Auden’s work into herself and projecting its resonance onto her own life. Such is the mutualistic nature of Marraccini’s autobiographically-inflicted criticism: “Every queer person I know has this story, their First, but mine was more a mythos, a more storylike story than anyone else’s I had ever heard.” Reading this new form of criticism is invigorating—it breaks down the traditional critical barriers that exist between works of art and one’s own life. Yet Marraccini also recognizes the implicit dangers of this one-sided obsession: “This is what happens when you get too close to art, undiluted, when criticism isn’t there. It lays its eggs in you. It breeds. It becomes your first kiss, your first lover, your first experience of everything before you even open your eyes.” By filtering her own experiences through the lens of art criticism, Marraccini eventually finds the tangible world more and more distant.

This new form of criticism, however groundbreaking, is also subject to the tenuous structures of genre, audience and form. “I think it is true to some extent that critics are ventriloquists, that we swap out the tongue lice in our fish mouths to speak differently,” Marraccini reflects. “There is a voice for the TLS, a voice for the internet, and so on.” The critical voice must be fluid and adaptable to different structures in order to thrive. Just as Dillon worries about his authority as an art critic who simply “makes connections,” Marraccini’s training as an art historian is difficult to reconcile with her personal obsession with certain artists or works. Critical distance no longer exists in this book, nor does subjective criticism. Instead, she suggests, criticism must give way to more autobiographical, emotional forms, ones that expose rather than couch in academic jargon: “the new language better come in fast and arterial, bloom into our thoracic selves . . . There is no thrill to writing about dead art for a dead world in a dead city.” Later, she wonders, “Does criticism keep anyone from dying but critics, we the parasites, feeding on the art to make reviews and essays in the papers?” She decides it doesn’t matter: “It keeps us alive, the tapeworms, maggots, fig wasps. We fight to thrive too.” In this way, the nature of criticism is intrinsically parasitic, forever giving rise to new and evolving forms of writing and art.

In his recent book Professing Criticism, John Guillory suggests that literary criticism has largely become a product of academic circles rather than aimed at a general public. In order to survive, new forms of criticism have increasingly moved toward a critical/creative mode exemplified in personal essays that meld traditional forms of criticism with autobiography. Dillon and Marraccini take this a step further, suggesting that criticism thrives off personal attachments to art rather than detached, analytic research, and must encompass the individualized emotional connections formed by viewers. Both Dillon’s affinities and Marraccini’s parasitic criticism thus become a phenomenological immersion rooted in embodying the art both writers encounter, resulting in an affective emotional experience that extends to their readers. The authors’ own genuine enthusiasm for these works draws us to them in turn, suffusing them with a love that makes them come alive on the page. By transferring their emotional connections to their readers, Dillon and Marraccini enable us to newly embody these affinities, completing the cycle of criticism by creating a mutualistic bond between artist, critic, and reader. This collaborative process may represent the future of criticism, a new form of creation that transforms works of art into living, evolving things.

Eliza Browning is a master’s student in modern and contemporary literature at the University of Oxford and an editor at The Oxonian Review. Her arts and literary criticism has appeared in Untapped Cities, The Oxford Review of Books, The Oxonian Review, Boston Art Review, Asymptote and Chicago Review, among others.

This post may contain affiliate links.