[Archipelago Books; 2021]

Tr. from the Bengali by Nandana Dev Sen

Translated and introduced by her daughter Nandana Dev Sen, Acrobat is an illustrative and delicate portrayal of Nabaneeta Dev Sen’s immense poetic life. As a prolific scholar, Nabaneeta published over eighty books in Bengali, including children’s literature, criticism, plays, and poetry. As her daughter notes, while her books of prose outnumbered her poetry collections, poetry was her most essential and immediate form. That is, poetry was a material necessity for Nabaneeta, as evidenced by her belief in the vitality of poetry as “central to a woman’s freedom” and “a means of [their] survival, it is a window through which [they] can breathe.” Further, as Nandana writes, “Nabaneeta had a profound and primal need for poetry, not only as a way to cope, but as a way of forming herself.” Nabaneeta would often say to her daughter: “‘How do I know who I am until I have ‘written’ myself, and read myself? There I was, me, Nabaneeta, taking shape, on a piece of paper.’” Themes of poetic self-making weave throughout the five sections of Acrobat and inform Nabaneeta’s obsessions with kinship, language, translation, and time. Acrobat symbolizes a culmination of Nabaneeta Dev Sen’s poetic life that began with her birth from famous poet parents, her naming by Rabindranath Tagore, and ended abruptly during this intimate collaboration with her daughter.

The first section, “The Unseen Pendulum,” begins with the collection’s title poem, “Acrobat.” It is an enduring opening as it alludes to the dangers of assumption and time, and swiftly identifies Nabaneeta’s ability to make language pliable to uncover both the beauty and danger of any given moment. “She thought,” it begins, “she could juggle time with both hands, / Play with the now, right next to the then,” then to “glide, so smooth, along the tightrope, / She thought she could do absolutely anything at all.” And, chillingly, the poem ends: “Only once in your life will the rope shiver.” This ending, stated with such certainty, marks a distinct shift from the poem’s previous hesitation. In some capacity, the change in tone characterizes the whole of Dev Sen’s verse. That is, Acrobat often succors the reader to feel at ease to only, a page or several lines later, grow unsteady. Of course, this progression demonstrates a poet who wishes to discover herself on the page.

Nabaneeta performs this lesson many times over, both in the hopeful sense: “She is only asking for time / Five minutes, nothing more / Because she knows / She can easily stretch / Those five minutes / Into a lifetime.”; and the adverse: “Because I keep crashing / into walls, I have now / come to know them all. / Eyeing an open door / I keep trying to run out — / but it’s just another wall.” Her poems open space for the nuances of these varying perspectives to build, lengthen, and then suddenly disappear. This is particularly true of her longer poems, where she often details the boundaries of in-depth personal narratives that realize the triumphs and pitfalls of dense emotion. For example, in the book’s third section, “Sapling of a Heart,” the poem “That Girl” follows a girl who is “chased” by affective forces such as sorrow, fear, love, and exhaustion simply to find herself in Dev Sen’s refrain: “She keeps running and running.” Only in the final stanza is the girl able to find reprieve, live in the present, and allow the weight of her constant running to transform then dissipate:

Now the girl runs without a care,

Both arms held high above her head —

At last

She is chased

Only by her destination.

Here, Nabaneeta emphasizes that the poetics of self-making exist as a reaction to circumstance and the uncertainty of time. The girl as subject is a vehicle for existential unease. She is an example of Dev Sen’s ability to articulate the folds of living both physically and intellectually, as the self develops in response to simply being alive. Dev Sen shifts affect from the adverse to the generative, creating a sense of closure that is also echoed in the poem “First Confidence” that begins Acrobat’s penultimate section “Do I Know this Face?” The first-person poem follows the speaker through a “monsoon morning” where “curtains toss,” “every door flies open toward the past,” and the speaker wraps their “body in drenched hair.” This unsettled scene once again resolves in the present, in a moment that finds solace in material uncertainty and an embrace of unknowing:

Now, lifting my eyes, I stand tall

and, in this free and weightless light,

I say with confidence, for the first time —

I have forgotten all.

Throughout her life, Nabaneeta’s relationship with translation was complicated; she believed in both the value of translation and was aware of the material dangers it posed. She translated countless works from a multitude of languages such as English, Bengali, Chinese, Russian, Japanese, and Hebrew. However, she chose to compose her poetry almost strictly in Bengali and did not care to translate her own poems into English. As Nandana writes of this political choice, her mother “saw this dilemma as a crisis of loyalty, and of identity — not only because she belonged to a generation of writers who rejected the colonizers’ language, but even more critically, because she was deeply worried about the future of regional languages and literature in India.” This bifurcated logic deepens a sense of unease because it plainly transmits Nabaneeta’s desire to preserve and uphold tradition. Her efforts also reflect a nervous want to move forward, to keep time going. This stance is related to her hesitation to translate her own poetry, as Nandana points out, “she agonized over every syllable of every poem she wrote in Bangla, but once she completed a poem, she felt her work was done. ‘I would rather write a new poem,’ she would say, than revisit one through translation.”

This sentiment, however, is not completely unyielding, for Acrobat itself does contain a handful of poems that Nabaneeta composed in English, translated herself, and translated with her daughter. Additionally, as is acknowledged in the introduction, Nabaneeta believed that “good English translations of Indian literature are urgently needed today as lifesavers, to protect regional literature from being wiped out in the tsunami of globalized Indian literature in English.” Nandana’s translation of Acrobat, then, is a material necessity that achieves her mother’s standards in a compelling and artful way. The collection also goes a step further, as it is a testament to lives committed to the beauty of kinship and its enduring ability to inspire poetry. This is evident for a final time in the form of the collection’s last section, “Sacred Thread,” where you find the only poems that Nandana and Nabaneeta translated together, including the closing poem, “Return of the Dead,” that celebrates a lifelong commitment to India, literature, and family. “Receive me then, Kolkata, / I am your true love, your whole world,” it begins in declaration, and concludes with a singular sense of belonging:

Here I am, returned from the dead —

Yes, it’s me, your childhood sweetheart,

Your world of passion, your old flame,

Your very own

Nabaneeta

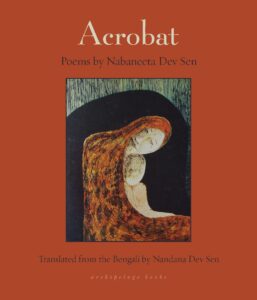

This intimacy between mother and daughter could only be prefaced by Acrobat’s cover art: a painting by Tagore called “Mother and Child” that features an Indian woman in an abstract, red saree who is hunched over and holding a small, faceless child. She bears a soft smile that is countervailed by her eye that looks off, away from the warm scene, as if to say what Nabaneeta starkly does at the start of a poem: “One day this child too will die.” Although somber, this message emphasizes Acrobat’s impulse to perform, in translation, a kind of kinship that embraces materiality and moves forward with the hope of keeping careful watch over a mother’s simple yet capacious verse.

Zachary Kinsella is a writer and musician from Dorset, Vermont. He completed his master’s in English from Clemson University in 2021 with a focus on the intersections of poetry, queer and affect theory, and phenomenology. In February 2020, he presented a paper on W.S. Merwin at the American Literature Association’s symposium “American Poetry.” He also has a forthcoming review of Nathan Snaza’s Animate Literacies in the Journal of Modern Literature.

This post may contain affiliate links.