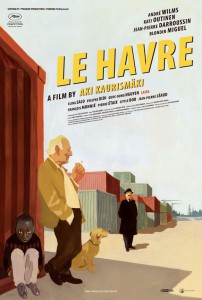

Le Havre (2011)

dir. Aki Kaurismäki

It’s no secret that 2011 was a big year for nostalgia in the movies. The silent pastiche The Artist garnered acclaim across the board, winning the Golden Globe for Best Comedy/Musical and the Oscar for Best Picture. Scorsese’s Hugo, I’m told, not only winks at the early cinema of the Lumière brothers but also casts Ben Kingsley as cinematic magician Georges Meliès.

The trend wasn’t just limited to Hollywood, either. A quick overview of the reviews for Finnish director Aki Kaurismäki’s film Le Havre reveals that cinematic hat-tipping extended beyond the mainstream. The critics didn’t fail to notice the many references embedded in Kaurismäki’s characters and landscape, from the Buster Keaton-inspired protagonist to a come-what-may proletariat reminiscent of certain French films of the 1930s and ’40s (notably Carné’s — though his poetic realism wasn’t exactly “rosy,” as one reviewer put it). The “nostalgia cinema” designation and its tidy “Hollywood” ending grossly complicate Le Havre, an impossible fairy tale firmly rooted in present-day France’s post-colonial, post-9/11 atmosphere of xenophobia.

The film consists of two overlapping stories: in one, the wife of a poor shoe-shiner (Marcel Marx) suddenly falls ill and is diagnosed with an unnamed fatal ailment. Ignorant of the seriousness of his wife’s disease, Marcel struggles to get by while she is in the hospital. The second intrigue begins shortly after the wife’s hospitalization, when Marcel becomes the protector of a young African refugee stranded in Le Havre and wanted by the police. While the former is a (forgive the cliché) timeless tale, the latter imposes a strict temporal framework, as it details an international crisis that is still unresolved today.

Over the past decade, thousands of asylum seekers have passed through northern France (in particular, the Nord-Pas-de-Calais coast) in an effort to cross the Channel into England. In 2009, Calais was the center of controversy after French Immigration Minister Eric Besson ordered the dismantling of “la Jungle,” a major makeshift migrant camp where hundreds of “sans papiers” (literally, “without papers”: asylum seekers and economic migrants from the Middle East) lived in overcrowded and squalid conditions with the hope of reaching England. Idrissa, the young refugee in Le Havre, is a sans papiers and as thus, is introduced in this context. Kaurismäki uses actual news footage from the September 2009 event, removing all doubt of the time period. Even today, Calais remains a major limbo spot for migrants: the Calais Migrant Solidarity organization gives the average number of migrants living there at around 300.

Over the past decade, thousands of asylum seekers have passed through northern France (in particular, the Nord-Pas-de-Calais coast) in an effort to cross the Channel into England. In 2009, Calais was the center of controversy after French Immigration Minister Eric Besson ordered the dismantling of “la Jungle,” a major makeshift migrant camp where hundreds of “sans papiers” (literally, “without papers”: asylum seekers and economic migrants from the Middle East) lived in overcrowded and squalid conditions with the hope of reaching England. Idrissa, the young refugee in Le Havre, is a sans papiers and as thus, is introduced in this context. Kaurismäki uses actual news footage from the September 2009 event, removing all doubt of the time period. Even today, Calais remains a major limbo spot for migrants: the Calais Migrant Solidarity organization gives the average number of migrants living there at around 300.

The film’s opening sequence establishes the curious mixture of the past and contemporary that colors the entire work. While introducing Marx and his colleague at work — staring at shoes in the train station — Kaurismäki abruptly interjects an old fashioned criminal-detective subplot (easily lifted from Jean-Pierre Melville’s famous gangster films) before trading in the noir for a Pagnol-like feel buttressed by sentimental, accordion-heavy background music.

The film’s frequent bar scenes, full of world-worn regulars and kitschy decor, coupled with the long shots of the harbor, bring to mind Marcel Pagnol’s iconic Marseille in the 1930s (though imagining Raimu in Normandy is probably as good as blasphemy). Furthermore, the film’s hopeful proletariat (the protagonist’s name last name is Marx!), lovable for its witty cynicism and collective spirit, mirrors the optimistic days of France’s Popular Front (again, early ’30s). Many characters are straight sketches from the past: the ostensibly austere, selectively kind-hearted Inspector Le Monet, for example, is derived directly from film noir and Melville.

The list continues, as Le Havre’s nostalgia is in the details. Jean-Pierre Léaud, known to most as Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel (The 400 Blows, Stolen Kisses, etc.), is cast as the prying neighbor who denounces Marcel to the police. To a certain degree, Léaud’s presence offers an automatic reference to the legendary directors of French cinema (albeit a different time than Carné’s), just as it did in Olivier Assayas’s Irma Vep (in which he played an aging French director remaking the silent classic Les Vampires). As for Marx’s wife, those familiar with classic French film will recognize that her name, Arletty, gives homage to the famous French actress who, with her unmistakable accent, was French film’s “working class” go-to heroine during the ’30s and ’40s. All these details proffer a familiar lightness that tempers even the darkest scenes and pervades the hour-and-a-half to come.

* * * *

In contrast with the structured familiarity and sentimental indicators of times past, Kaurismäki toys with the expected standard by punctuating and updating the landscape with outsiders. For example, the Finnish actress and Kaurismäki regular Kati Outinen plays the aforementioned role of Arletty. Her slow, accented French does little to belie her non-native status; Claire, the bar owner, overtly hints at her status as a foreigner and thus “non-French.” Marcel’s friend and co-worker, Chang, is another “outsider,” despite having lived in France for over a decade. Upon watching a news story on TV about refugees in the real-life Jungle in Calais, he admits to Marcel that he, like the refugees, technically “doesn’t exist” as a citizen. His papers give his identity as Chang, a Chinese immigrant, but he is in fact an illegal immigrant from Vietnam. His real name is never given, but he’s “gotten used” to being Chang.

Of course, the most important outsider is Idrissa, a boy from Gabon who travels clandestinely with a group of Africans hidden in a cargo container, destined for London. Due to a “computer error,” the container is unexpectedly stranded at the Le Havre dock for two days (after the discovery, a morbid question lingers: how long would they have been trapped otherwise?). When the officials open the container, Idrissa boldly escapes and eventually presents himself to Marcel Marx, who, with his neighbors, does all that he can to help the boy and deter the increasingly omnipresent Inspector Monet. Idrissa’s backstory as a refugee is common: his mother, whom he plans to join, is living in London and working in a laundry; his father is dead (under suspect conditions in Africa), and his grandfather was arrested with the other refugees. With the help of the grocer, the baker, the bar owner, and his friend Chang, Marcel raises the funds necessary to pay a skipper who will transport their dangerous “cargo” across the Channel to find a new life with his mother.

Kaurismäki’s deadpan humor makes Le Havre a little hard to take seriously, but all whimsy loses a little luster when paired with the blatant awareness of the discriminative politics and xenophobia that have defined French immigration legislation for the last decade. At times, Le Havre satirizes the Islamophobic, fear-mongering attitude of the press in a way that elicits ironic laughter from the audience. For example: as Marcel shines a man’s shoes, he glimpses a newspaper, whose front-page article details the recent runaway and his captured traveling companions. The headline reads, “Armed and Dangerous? Connections to Al Qaeda?” Below is a photo of the women and children sitting in the dark container, receiving help from the French Red Cross. At other times, Kaurismäki inserts harrowing images rather matter-of-factly, without overt commentary — such as the aforementioned scene in which the bar TV plays footage of the September 22, 2009 dismantling of la Jungle.

* * * *

The fact that Kaurismäki pays so many tributes in the film is tricky. The nostalgic trend in cinema is symptomatic of turbulent times and the desire for a unified cinema that espouses a national identity. Such was the aim of “Tradition of Quality” in France during the years following World Word II, characterized by bland literary adaptations and costume dramas (denounced in the 1950s by Francois Truffaut and other rising New Wavers behind the Cahiers du cinéma).

The fact that Kaurismäki pays so many tributes in the film is tricky. The nostalgic trend in cinema is symptomatic of turbulent times and the desire for a unified cinema that espouses a national identity. Such was the aim of “Tradition of Quality” in France during the years following World Word II, characterized by bland literary adaptations and costume dramas (denounced in the 1950s by Francois Truffaut and other rising New Wavers behind the Cahiers du cinéma).

The French suffered a similar identity crisis in the ’80s and ’90s, linked in particular to immigration. Obviously, the fact of Kaurismäki’s non-French status rejects this interpretation as he has no reason to idealize a French past — particularly given that such a past is a return to colonial France. The national history that includes Renoir, Carné, and Jean Gabin is not his, nor is even the present that includes Sarkozy and tough legislation on immigration his direct concern. Ultimately, however, the rosy, old-time charm never totally overrides the current situation. Even at its sweetest moments, the film is never pure escapism; the sugarcoated denouement doesn’t quite fit with the underlying reality, and for good reason.

While I won’t give the ending away, I will admit that things work out for all main characters. Traditional, mainstream cinema typically follows the Aristotelian principle of catharsis: after a film ends, the audience is purged of emotions — “emotionally spent,” Walter Kaufman suggests — thereby placated and ready to rejoin the world outside the theater. Aristotle, of course, was discussing tragedy, but Marxist theory has expanded from the idea of catharsis to a rejection of the emotional satisfaction elicited by mainstream film narratives (and institutionalized by the Hollywood happy ending), which benumbs the populace, removes desire for change, and re-inscribes a certain ideology.

Considering the political subtext of Le Havre, Kaurismäki’s extreme happy ending warrants consideration, as its effect does not entirely placate the audience. Kaurismäki offers his comedies’ endings with a twinkle in his eye, like a used car salesman handing over the keys to a “like new” vehicle whose true mileage is three times what’s reported. Something mischievous is afoot. Le Havre satisfies the immediate need for a tidy package, but only temporarily: the truth is, given all that we know we’ve moved past the possibility of a happy ending. What Kaurismäki suggests is a comic parody of one; and while initially appealing, upon further reflection it is as laughable as the feel-good Christmas scene that closes The Night of the Hunter. If this isn’t parody, it is a regressive “white savior” narrative, which is as problematic as it is unsatisfying on a greater scale (France still doesn’t know how to “solve” the migrant problem).

So what is the overall effect of Le Havre? Despite the reality of the migrant crisis, the film is still a comedy, and few moviegoers are deeply shaken by the time the credits roll. Without getting into a discussion of intentionality, it’s worth mentioning that Kaurismäki does reopen the debate about the situation, which has been largely absent from the news since 2009. In addition, he inspires us to ask what we really want from a film, and if being comfortable is good enough.

This post may contain affiliate links.