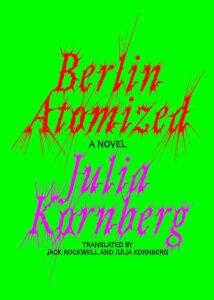

[Astra House; 2024]

Tr. from the Spanish by Jack Rockwell and Julia Kornberg

I finished Julia Kornberg’s debut novel Berlin Atomized shaking, knotted up in my living room chair, feet against one arm rest in an attempt at immobilization. When I stopped feeling paralyzed, I knocked on my roommate’s door and told her, “I just finished this book, and I don’t really feel okay. Can I just talk to you for a few minutes?” I wasn’t sure what to do with the feeling this book gave me.

Kornberg originally wrote the novel in the late 2010s as a series of short stories. In 2021, it was published in Argentina, where she grew up, as Atomizado Berlín. Jack Rockwell, who had previously helped translate one of Kornberg’s short stories, asked to translate the novel, and they agreed to collaborate on the English translation. Despite its conception more than five years ago and setting in a parallel present and speculative near future, Berlin Atomized feels current and urgent.

How would you feel on an island of meaningless “culture” surrounded by a mote of tragedy and war? For Nina Goldstein, the answer is mostly: bored. Her brother, Jeremías, feels too much, little of it good. Berlin Atomized alternates between the two siblings’ perspectives, both in first-person, making the transition from one to the other elusive, spilling their genetic and contextual overlap into the story itself. Their third sibling, Mateo, joined the military and died in Tel Aviv, forfeiting his narration. The novel follows the remaining siblings from childhood in Nordelta, a gated community in Buenos Aires, to Uruguay (together), Paris (Jere), and Berlin (Nina). In the section “Rich Kids Want to Die Too,” Nina exists in a state of derealization, repeating I am not asleep to herself. But when she breaks from her fugue of boredom and strikes up a relationship with a man she sort of likes, she bathes for six hours after they first have sex. She wants more from life but doesn’t want it to infect her. After merely being outside, she has “an absurd need to get the dirt off me.” Jere, on the other hand, dives into counter-culture as much as a rich kid can. He attends a public school, unlike his siblings, and goes to protests and metal concerts with his two friends, Tobi and Li. As Nina tells the reader later, “We Goldsteins had entered a limbo of bohemia from which we couldn’t escape.” What seems a lamentation becomes more observation when she cuts herself off: “Even if we wanted to—and I didn’t, I don’t.”

These are the happiest times of the Goldsteins’ lives, unfulfilling as they may be. But at the end of their childhood, their home, however their love and resentment tangles around it, does not want them. Nina doesn’t see it as her choice to leave Buenos Aires—rather, “the city expelled us.” Nina leaves for Berlin only after Buenos Aires makes it abundantly clear it has no kindness left for her, “after my guy friends began developing hideous addictions, my girlfriends dying at feminist marches—after the second time I was put in jail without explanation.” She does not leave specifically to find her new lover, Ossip, but because “I had just accepted that I should surrender myself to flight. I saw that, like everyone else, leaving was my inexorable destiny.”

In most literary fiction I have read about middle- to upper-class people flailing around in “modern society,” authors focus on technological advancements, the “online world,” how personal relationships and art and quotidian rituals have changed or turned dystopian. But few lean heavily, if at all, into political questions, or even much into the particularities of a culture, beyond it being “online” and peculiar. Kornberg trusts that her readers want and can handle more than that. My thesis advisor in college often told me to work on developing the milieu in my stories. The “life and times.” Berlin Atomized has a spectacularly dense, specific milieu. Nina and Jere aren’t just observing the peculiarities of their world; they’re living in it. They say things that I have to look up because I want to be in on the joke— “Montevideo is just like Buenos Aires if caffeine had never been invented and Maradona had never made that goal.” Nina calls Jere’s friends “Trotskyite wannabes,” whom she resents for taking on Kirchnerism simply because it has “come back into power and vogue.” Kornberg points out the uneasy conflation of art, culture, and politics, all under the umbrella of self-branding and aesthetics.

Kornberg’s humor, like her characters, is politically and artistically specific as it is cynical. When the siblings walk along the side of the highway, they ignore honking cars because “we both harbored a simmering death wish, so it didn’t really matter much to us.” They spend time “liquidating our days, feeling like gigantic teenagers every time we bought red wine instead of Klonopin.” Kornberg’s descriptions are inspired, unusual. Ossip has a nose “just a bit hooked, like Knausgaard if Knausgaard were twenty years younger and never went to the gym.” Every occurrence is shaped by Nina and Jere’s particular cultural reference points. When the Eiffel Tower falls in an explosion, Jere thinks it’s “like a model collapsing on the runway, breaking her bones in a precipitous fall. High heels in the air. Adieu, Jean Paul Gaultier.” This humor is not exactly hopeful, but it holds the reader fast for the majority of the novel until the end, when its rope unties and loses them in the sea of existential aimlessness that Kornberg has been filling under them.

We can’t use irony to cope with catastrophe forever. Humor can bond a reader to characters, but it can also put a certain distance between us and them, them and the trauma of their world, us and that trauma most of all. And Kornberg tells us No, you won’t get out of it that easily. You have to feel it, too. She pushes the reader down under the full force of Nina and Jere’s negative feelings. The boredom, first, and then the anguish. The impossibility of doing anything worthwhile. Whether this is the Goldsteins’ destiny or all of ours is unclear.

Those of us in the so-called “art world” might see the Goldsteins’ boredom and pose artistic creativity as an antidote—maybe art is the thing we all should be living for. But art, Nina believes, is politically futile, especially if it is made within the art world and in pursuit of that world’s admiration. The art promoted by large institutions falls in the laughable center of the “self-serious” and “weird for weird’s sake” Venn diagram: “rows of enormous phalluses composed entirely of casettes,” “perfectly symmetrical drawings drafted in menstrual blood,” “a series of selfie videos taken on [the artist’s] iPhone as he walked through Scandinavian cities dressed as a woman.” Art gets away with being lazy and performative because the performance is so well-branded. In Berlin, Atomized, Kornberg asks us to parse the difference between art and mere aesthetic. Photos in the media, Nina observes, tend to show “an aesthetic of suffering that could always remain just that: an aesthetic … beautiful photographs, made horrible by what they suggested. They were easily consumable and mimetic.” Nina does not consider this creativity, if art at all. When Ossip, whom she meets at an art festival where his work is displayed, asks her about her creative life, she says she has none. To the reader, she adds, “unless documenting everything about one’s own life, that collective mania that had shaken our last few years, had some artistic intelligence to it, and wasn’t just pathological.” Rather than a true culture, an artistic “scene,” these rich kids have performative aesthetics, nostalgic reenactments of more purposeful scenes that never belonged to them.

The more they hurt, the more authentic their performance feels. Kornberg brings us a translucent portrait of the tortured artist, an archetype Jeremías slips on like a tailored suit and which Nina fights but ultimately falls into even more. The Goldsteins’ emotional turmoil, and that of their friends, is real—rich kids want to die, too—but it’s also a part of their self-branding, their appeal to those outside of themselves. Jere tells us that his friend Tobi hated himself, hurt his ears with loud music, in the same breath as he says “Li and I admired him anyway, we liked him like that.” Nina describes Jere and Li as “so beautiful and so talented, so clearly doomed,” linking the fated tragedy to their charisma.

Jere especially wants to die. He hurts himself. He turns to prayer. Kornberg doesn’t serve the reader vivid descriptions of this pain to gawk at, although, to Nina, “his decline was fascinating.” This comment opens up an often unspoken, masochistic ideal of the art world: If one’s art is meant to be both serious and self-centered, they themself must be a bit of a tragedy. Jere clings to his guitar, writes music as if to mold his genuine depression into a shape we recognize as socially appealing, worthy of fascination if not love.

Nina, meanwhile, remains disillusioned about the importance of art. At her friend Angelíca’s urging, she agrees to join the New Resistance, a guerilla activist group that in part hopes to shock people out of their disaffectedness by disseminating gruesome images of global tragedies onto their phones. Whether taking these photos truly helps Nina regain a sense of purpose in art depends on who you ask. Ossip calls Nina’s photographs “emotional bulimia,” but Angi finds them brilliant, “an archive of her sadness.”

It’s hard to read the end of this book and feel anything but dread.“History repeats itself,” Kornberg writes. “First as a tragedy and then as a tragedy and then as a tragedy, and then again.” Angi asks of Nina, “Didn’t I want to change the course of history? When would we stop being melancholic about the state of the world and finally dare to do something to change it?” Maybe the idea that hope alone can save the world is powerful to some people. To me it’s thin, unconvincing, tears easily. think Kornberg could say the same. Berlin, Atomized is not a book you turn to for hope (and it’s certainly not a book I’d recommend reading while switching depression medications (mistakes were made there)). But it is a book I think we need more right now than we need a hopeful book, anyway. Kornberg demands her readers reckon with discomfort and decide, actively, what they will do. She doesn’t want those privileged enough to be bored right now to break from their stagnance because they are hopeful for a better world. She wants them to do so in spite of their hopelessness.

Of all the book’s characters, Angélica most strongly believes some sort of revolution is possible, and she hasn’t lost all belief in art either. This doesn’t look like optimism: “These days,” she tells us, “still filled with anger and war and the never ending defeat of the left, I am forced to cling to life.”

Forced. Who’s forcing her? Kornberg left me treading water, searching for a moral that would feel warm and comforting, a moral that did not exist. It would be easier to know how to feel about Berlin, Atomized if it ended with some clear-cut victory for the New Resistance. Some tangible improvement to any of the societies these characters have flitted between. But an easily digestible ending isn’t necessarily a good one. I have decided to hold onto Angi’s quote because, for some reason I can’t always articulate, I don’t want to die either. To proceed with enough anger, enough hurt, enough desperation to not care about hope, about the odds, about history repeating itself, is not the option I’d like to choose, but it is the best one I’m left with.

Erin Evans is a writer from Michigan, now living in New York. She studied Creative Writing and Literature at the University of Michigan, where she also worked as an arts writer and editor for The Michigan Daily. Her essays and criticism have appeared there and in Vestoj.

This post may contain affiliate links.