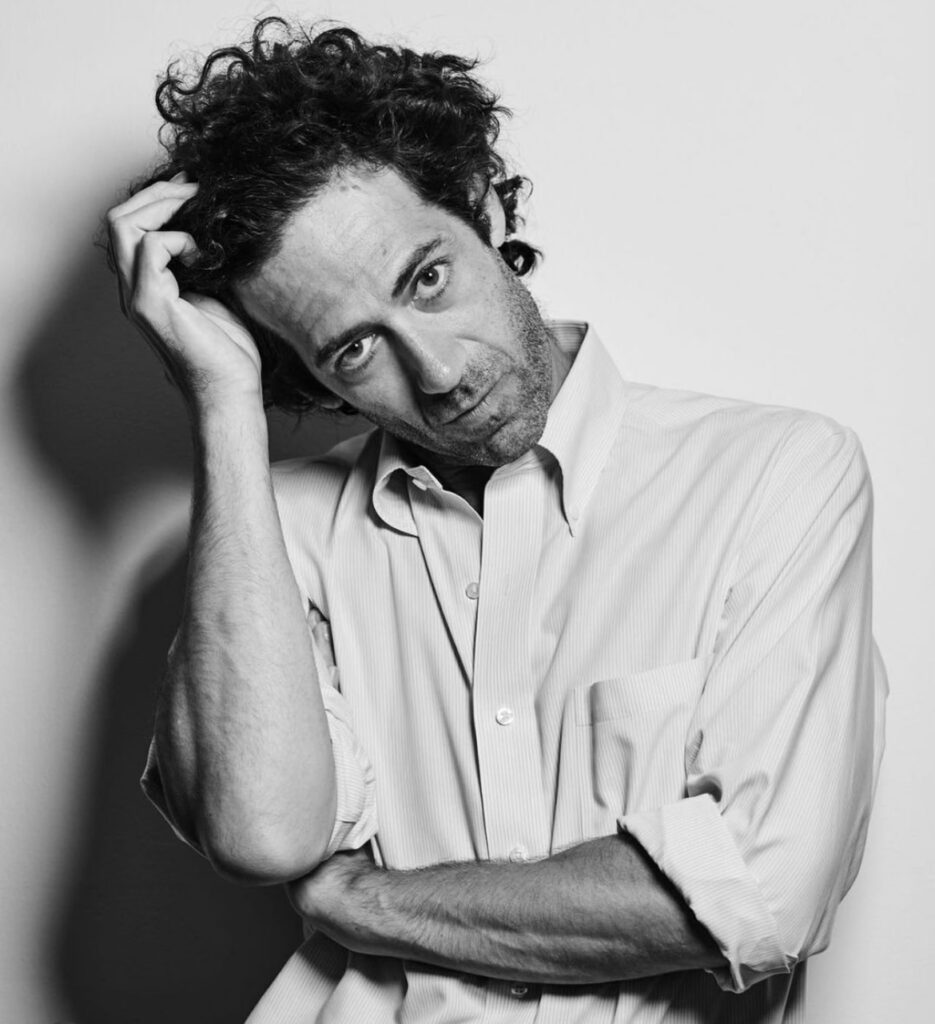

Julian Tepper is the author of four novels: Balls; Ark; Between the Records; and his most recent, Cooler Heads. I have been a huge fan of his work for over a decade. But with his latest novel discussed below, Cooler Heads (Rare Bird Books), we did that thing that writer friends do: we exchanged early drafts of our manuscripts, because we both were working on new novels. Sharing early work that isn’t quite “there” yet, isn’t ready to send out to publishers or even agents, is an act of trust, and vulnerability. A writer and the manuscript are in an emotionally raw stage. A draft is done, maybe even a second draft is done, after so many early drafts. The manuscript isn’t ready for submission, but the writer wants eyes on it. What followed was a long lunch, discussing our works in progress, and many follow up emails.

Now Cooler Heads is out in the world, in all its glory. It’s a phenomenally fast paced novel, about love and passion, about a couple and their child being born, about ambition and the arts in New York City. Told in the first person by Paul, a journalist who writes a newsletter called “Cursed Corners” about troubled building in New York City. He is in love with Celia, a Southern transplant to New York, a wildly ambitious and talented painter who is in an open marriage. What follows is a heartbreaking tale of their life together, which includes a realistic birth scene, a fantastic trip to an art residency in Poland, the politics of the art world, many descriptions of cursed corners that mirror life itself, and crystalline portraits of Paul’s mother who lives in a hotel and my favorite, Celia’s Southern husband Graham. And more. How can there be so much in a novel I read in two sittings? It’s a remarkable achievement, by a seasoned writer. It’s fun to read, yet emotionally intense. It’s also a blueprint on craft.

Paula Bomer: I read an early draft, and you read an early draft of my forthcoming novel, and having just finished reading your published novel, the actual novel out in the world, was so fascinating. The novel centers on family love, and the end of a family. And somehow, I want to connect the two things, the writing of your novel, the early draft of it and the solid, crystalline novel it turned into. It’s as if the writing of the novel, from the early draft into a finished body of the work mimics the splintering of a family into pieces, and the making of the pieces into distinct entities.

Julian Tepper: That’s a really interesting way of looking at it, Paula. I do like to think that each scene could stand alone as distinct entities. I want each scene to hit as hard as the next one—no filler, please. And so maybe a kind of self-centeredness attaches itself to each scene—the individual moment putting itself above the whole in the same way that individuals within a family so often do and thereby cause a fracture. Of course, in the case of the novel, I do hope it all holds together.

It absolutely holds together. And yet, the book starts with an already fractured existence, as the character Celia, with whom the narrator Paul is madly in love, is living with her husband Graham, in an open relationship. In this first chapter, the entire narrative gets rolling. It’s a first chapter that has such a light touch and yet all of the themes which are part and parcel to the storyline are set in motion. Open marriage, love, and then—boom—family. Celia is pregnant. She is ready to move in with Paul, just as he was about to give up on her.

I’m so glad to hear you say it was executed with a light touch. If you knew how many times that first chapter was re-written, I can assure you that the touch felt very heavy by the time I was turning the book in. On the other hand, part of that rewriting and getting all the themes in there and hopefully bringing that light touch—it is trial-and-error and the unconscious mind doing what it does. That is, it feels kind of like luck to me. I say to myself, “What if I write it like this? No. That’s not it. What about like that? No, no, no, no. What about this? Oh, well now that’s starting to work.” And on and on. And then the conclusion that something is now “working” is based on what? Gut feeling, I suppose. All that said, getting a first chapter to do what a first chapter must—this is the kind of stuff that keeps me up at night! So maybe it’s just the power of fear to bring good results from time to time.

“If you knew how many times that first chapter was re-written”—this is fascinating craft information. Often what feels so fluid in a work was really painstakingly reworked. The word “sprezzatura”—of work “without apparent effort”—comes to mind. I enjoy sentences and novels that show the effort and take effort to read. It’s its own thing. But that flow, that easiness of narration in Cooler Heads, like many fast paced novels, “page turners,” is actually often hard fought.

Celia is a painter and Paul is a writer. Celia is a transplant to NYC, a seeker who sees NYC as the place where artists go to “make it.” Paul is a native New Yorker. It’s not as if he takes for granted his position, but the hunger that Celia has—the possibilities that are available to her—are the stuff of dreams people like her aren’t afforded in their home states. In that way, I relate to her. But even a native New Yorker has to do the work, make the commitment and exhibit the talent. Paul has all these things. Paul writes a newsletter called “Cursed Corners” which has an audience. Celia says, “You have a voice . . . I want that, too.”

This is a subject that I, as a born-and-raised New Yorker, have so many strong feelings about: specifically, that experience of the person who comes to New York from elsewhere. I’m interested in that fresh energy, the thrill of being somewhere new, with every experience being your first experience in that place—and having that place be New York City. Could there be better? Especially with so many people having wound themselves up for a quarter-of-a-lifetime with the thought, “I have to get there!” I really used to envy the transplant, the new arrival. I wanted what they had, the opportunity to feel that I was in a new place. I would say that with age I’ve grown out of that feeling and have every bit of gratitude for all those pieces of my life that predate, say, age twenty-two, when I returned to my home city following four years of college.

And I always and still do envy the natives! To watch my sons grow up here was to see them have opportunities that I dreamt for them. But I insisted they leave for college. Fascinating that you once envied the transplant. It’s a bit traumatic! But yes, with wisdom comes appreciation and that is where you are.

The “Cursed Corners” in the book are scattered throughout the novel and serve an organic extension of the story – it is Paul’s day job as a writer, to find them and write about them. They also ground the novel, as all your novels do, into the love affair aspect with your home city, and how the changes, challenges, and serious problems of NYC are seen everywhere we go, everywhere we walk. There are reminders of things lost, which is the sort of purpose of Paul’s column. Oftentimes, they are lost out of greed, a landlord or developer wanting to make their fortune, and the foolishness of that sin. And so the columns also become beautifully metaphorical, the way they echo Paul’s personal life. Paul writes:

What circumstances create a cursed corner? In almost all cases, an original tenant has vacated location and a new tenant has attempted to insert itself—and its vision or perhaps lack of one—into that space.

When a family disintegrates, there are these empty spaces.

Thank you, Paula. It’s almost hard for me to talk about Cursed Corners because I get so excited. I like to think that they’re what sets the book apart from anything I’ve written previously. We have a story, we have characters, but then there is this whole other system at play that appeared from so many years of living in, going around, and thinking about New York. I have a whole book’s worth of Cursed Corners, dozens that didn’t make it into the novel. It’s an obsession, for sure. You’ve listed off many of the functions of the Cursed Corners, and I hesitate to name all the others because I feel like there’s this interpretative space there for readers to input personal meaning, and I don’t want to limit that. But one thing I will speak of here, one aspect of the Cursed Corner that gets directly at a family’s disintegration, has to do with the annihilation of the “good past.” As in, some good once occupied this commercial space—maybe it was a restaurant that was loved, a shop or venue that generated a whole art movement—and with its vacancy and the arrival of a new tenant, that history is almost always lost. And so in the case of the family, there are good years, aren’t there? A period when good things happened, right? Of course, yes. But with its disintegration, all that history goes away. It’s not remembered. Change is inevitable, but do we have to forget the good things that happened, too? Unfortunately, yes. Inevitably.

Well said. I love this response.

I was going to call this an “aside,” but the birth scene is really, really good. As you know, I love a good birth scene. Waylon is born, and Paul’s world changes. He now has his own family. Celia is no longer just his wife, she is the mother of his son. Graham remains in the picture, hopelessly devoted to Celia, now also becomes a babysitter. Paul is grateful and yet he realizes that it isn’t necessarily healthy for Graham. He has not moved on. How is it that some people exert so much power over another? Paul when talking to Graham about this aspect, confronts him with this disturbing truth, saying about his relationship with his wife that there may be “an imbalance of power.” Graham’s trajectory plays out perfectly, but when confronted with this by Paul, he says, “Generosity is what guides me in my life. It always has been. I like to give. If there was something you needed that I could give to you right now, I would.”

Here are two reactions to this very real thing: One, Graham is a Southern Christian, as was my father. When I was young and we were probably on a shopping trip for me, he said something to the effect of, “As you get older, it becomes more fun to give than to receive.” And yet, there is the children’s book The Giving Tree. Being generous can become a terrible curse. People will take advantage. People like to do that. In fact, a bit later in the novel, an art world mover and shaker is described as a “demented, sociopathic, hostile vampire fuck-suck piece of shit,” which I LOVED. They are not only characters in the movies. They exist.

Maybe we all require a degree of objectivity around giving, an outsider’s take. Like the tree in The Giving Tree—and it is a very apt example to pull in here—Graham becomes smaller and smaller through his acts of generosity, and for him this really is a problem. And yet neither the tree, nor Graham, have any sense of how their generous natures are hurting them, as they find personal happiness through giving. It is how they express love and create meaningful bonds with others. It’s sad and it’s funny, and it’s a subject that demands being written about. On another note, I also had no choice but to write about the transactional nature of most relationships in New York City. The character who delivers the line about the “demented, sociopathic, hostile vampire fuck-suck piece of shit” is almost toying with this very idea of generosity and its transactional nature in New York. After all, in that moment, she is using sympathy to try to get sex out of someone.

“The transactional nature of most relationships in New York City”! Wow. I think it might be everywhere. But NYC has its special, big city take on that human conundrum.

A counterpoint to this dilemma, the dilemma of “vultures,” another word you use in the novel, is this beautiful truth that fills Paul with hope and a different kind of love when he contemplates writing a book around his Cursed Corners:

This was the beauty of work, it was always there for you no matter what you lost. It was a safety net constructed over years through diligence and perseverance, and it would catch you at your worst times, suspend you in mid-air and then put you back on solid ground.

Researching and writing about Cursed Corners provides Paul with all the escapism he requires, this project in which he can distance himself from his own very real problems. That they’re about a kind of “vulture-ism” provides another advantage—he can feel like he is pointing out an evil and doing good by bringing attention to a serious problem. Which is how the Cursed Corners are framed at the outset: New York City is in crisis, as it has never seen so many empty storefronts in all its centuries, and because of this neighborhoods are suffering and therefore our citizens are, too. He is asking people to think about this, and, hopefully to do something about it.

And so, the work. You, like me, have a very strong relationship with your editor. He actually gets you, gets your process and puts the work in, too. This is special. All of your novels are very personal, in the vein of what was once referred to as “autobiographical fiction.” Roth, whose work we both love and admire if not worship, wrote that book The Facts due to all the outrage his fiction caused. But Cooler Heads is undoubtedly a work of fiction, and to circle back to craft, I feel like your editor not only understands what you are trying to accomplish, but helped you get there. Writing a novel requires a lot of time alone in your mind, alone with a story, but editors can help shape your story in ways that are profound. The changes I witnessed from reading an early version to this final, near perfect novel require a close reading, require feedback. Require a great editor, in many cases.

That is really kind, Paula. I feel very lucky. Having a close, long-lasting relationship with an editor. I’ve done three straight novels with Guy Intoci as my editor, Ark and Between the Records being the previous collaborations. I think of it as a dream realized. There are some important things that Guy understands about me: one, my aesthetic; two, that I’m a hundred times more interested in character than plot; and three, that I know that no one has the answer and that writing is its own experiment and we cannot determine whether the experiment has worked until we’ve given it a go. Meaning, we can talk and talk, but until I write it and determine whether the thing is alive and working, then who knows. And then it’s never personal and it’s never about being right or ego or anything like it. That is crucial. We both just want to have a very good book at the end.

This is what it’s all about, “a very good book in the end.”

Cooler Heads is a novel about great passion, great ambition, and the destruction of a family—all parts of the human existence that matter most in life. Is the title ironic? Is it what happens, the cooling off, the distance and vision necessary to make the heat of aliveness into a novel?

For me the title speaks to the act of suppressing the biggest, most difficult emotions—fear, sadness, anger—and the idea that those who are most adept at doing so can walk through life with the most calm, the most cool. Breaking down, flipping out, these are not the behaviors of those cooler heads, who maintain their poise no matter the circumstances. I won’t say more than that on the subject. Let the reader decide!

Paula Bomer’s latest novel, The Stalker, is forthcoming in May of 2025. She is the author of the novels Tante Eva and Nine Months, the story collections Inside Madeleine and Baby and other Stories, and the essay collection, Mystery and Mortality. Her work has appeared in Bomb Magazine, The Mississippi Review, Fiction Magazine, Los Angeles Review of Books, Green Mountain Review, The Literary Review, The Cut, Volume 1 Brooklyn, and elsewhere. She grew up in South Bend, Indiana and has lived for over 30 years in Brooklyn.

This post may contain affiliate links.