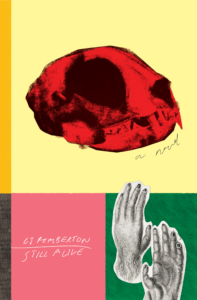

[Malarkey Books; 2024]

The question every restless idealist loathes: “When will you settle down?” Beneath these words is an implicit indictment of one’s perceived failures as measured against bourgeois imperatives—a stable career, an elegant home, a healthy marriage and well-adjusted kids.

The narrator of LJ Pemberton’s debut novel Still Alive—a young woman who goes by V, short for Virginia—is routinely confronted with this icy question by her mother. It’s not “will you settle down” but “when?” At this point in the story, V has reached her late twenties and lives hand-to-mouth in Brooklyn, a long way, physically and spiritually, from her hometown of Portland, Oregon. She has been searching for meaningful connection for quite some time, landing in the beds of one lover after another, “temping” and hating it in the so-called “gig economy,” and quietly harboring dreams of a writer’s life.

Years earlier, V asks her mother, “What did you imagine for your life when you were my age?” Her mother, evasive, simply utters, “That’s a cruel question.” She is divorced, drinks heavily, dates terrible men, and frequently inquires about V’s father, who has happily remarried and started a new family. Her son, V’s older brother, is off in India chasing immaterial salvation. So, if her mother doesn’t accept V as “unsettled,” it’s out of fear that V will end up a drop-out like her brother, or worse, like her: drunken and barely keeping it together, an exemplar of a life poorly spent.

Pemberton’s novel captures the wishy-washy ennui of twenty-somethings during the aughts, when Gen-X accusations of “selling out” still carried currency, when America was at war with at least two countries, thus presenting a tidy litmus test for young adults: you either endorsed or opposed the status quo. One might argue, as V does throughout the novel, that all these bourgeois standards are bunk, that the socio-political apparatus—capitalism itself—is corrupt and unfair. But it’s easier to make that claim than to wholeheartedly live by it without hypocrisy. As activists like to say, there’s a cop in our heads—or at least pushy parents. “I am hard on myself because I am accustomed to internalizing my mother’s casual judgment,” V laments. “Even when she is not around, I know the ways that she has given up believing I will make her proud.”

Still Alive is a circular novel. Painful scenes bob up from the depths of memory like bloated corpses after a shipwreck. They are gazed upon, scrutinized, sometimes mocked, and then they sink back down. The book opens with a gruesome scene: V, age seven, witnesses a fatal car crash in front of her house. It’s 1989, a “pre-hip Portland,” when V’s family was still together and “sitcom-solid,” or so she thought. In the crash, the driver’s head was severed, and it lies in the yard, bleeding and inexplicably implanting itself into V’s imagination forever. Like the best of novels, this one is nearly as much about death as it is about the living, specifically how the two are entwined. That V collects animal skulls—a bit of macabre kitsch—isn’t the half of it. “I began to wonder,” V considers, “if every heartache wasn’t just practice for the eternal separation between the living and the dead. As with any loss, it is not the dead who suffer, but the steady flaming fools left behind.”

From V’s childhood, Pemberton jumps to a post-9/11 reality in 2003. V is now in college and eager for kinship and love. Her best friend is an irreverent and delightful classmate named Leroy, a fellow free spirit who, for example, needs little convincing to take an overnight road trip to Boise for no other reason than a brief escape. One day, Leroy and V go to a basement punk show and she meets a girl named Lex. This chance encounter leads to a sticky affair—queer punk-rock puppy love. Much of the rest of the novel is an exploration of that on-again-off-again relationship: its delights and betrayals, the steamy bathroom sex and quotidian boredom, from Portland to New York to Los Angeles and back to the Pacific Northwest. “We bent time like tesseracts back then,” V reflects, looking back, “rolling around and through different places and ages like costumes we could try on and discard.”

If I were to categorize Still Alive, I’d call it a künstlerroman—a novel about an artist’s coming-of-age—but a sneaky one because one can forget that V is an aspiring writer at all. Her dreams are mentioned but ultimately take a back seat to her family drama and the push-pull of her whims as a bisexual woman. At some point V admits, “I am more a vampire of sensation than a lover or friend.” No doubt she is a glutton for sensory satisfaction, but often as a salve for the hardships she endures while attempting to maintain various relationships: familial, platonic, and sexual. As the critic Parul Sehgal describes the protagonist of Raven Leilani’s Luster—another novel in the contemporary künstlerroman canon—V “is neither heroic nor unduly tragic.” And that makes her a kind of everywoman of her generation.

It would be tempting, too, to frame the novel as an exercise in nostalgia. After all, the narrator writes from the vantage of the present, recounting formative moments along the jagged path into early middle age. But if nostalgia, according to Merriam-Webster, is “a wistful or excessively sentimental yearning for return to” the past, then this novel isn’t exactly that. We certainly do see fleeting joy in these pages—tender moments with friends and vivid queer erotica—but the past is mostly a painful or disappointing domain. What unfolds, then, is an impressionist interrogation of a valiant effort to forge a singular existence in an era of empty consumerism and vapid online life.

When one is dissatisfied, one dreams. One imagines a counterfactual life. V is no different than anyone else in this regard. She wonders aloud to Leroy what she might have done in another era, say a century ago. Perhaps she’d have become a sex worker, she says. These women were free from any societal expectations. They were outside that system altogether. This path is still an option in our time, of course, and V admits that she has considered it. “The quickest way to move capital from the surreally wealthy to the rest of us,” she says to Leroy. But that, too, is little more than a transitory thought. Leroy is a kind of refuge for V, a true friend, and at times her foil. He had been as idealistic as she was in youth, but he managed to find a place to call home, in Asheville, and settled into a simple life with a loving husband. His secret, in part, is his decision to eschew the popularity contest that is social media: “He reads. He talks to the man he loves, and when I visit, he talks to me.” Something like happiness is possible, the novel seems to suggest, but only after one removes all expectations of success or fame or glamor, and hunkers down with a loved one near the woods.

There is heartache and beauty all throughout this novel. Earnest turns of phrase butt against righteous indignation towards the raw deal we’ve been given as low-paid workers. Pemberton singles out the professional managerial class, the class of people under whom V is forced to sell her labor:

I held them in contempt for their unimaginative cosmologies. I despised them for their self-protective classism. They believed me theirs, by race, by class, by right, as someone safe, even as I held tight to the benefits of my invisibilities—access, ease, rent. The fuck else was I supposed to do? Get on board? I was not a true believer. From where I stood, the prize looked rotten. I saw too closely how money twisted the blessed into slaves of material maintenance, suspicious of their family members and friends and expecting always a kindness to come with an ask, and an ask to come with a mountain of obligation.

I keep thinking of Still Alive as a queer Fight Club (1996) for the millennial generation. Like that earlier Gen-X novel, Still Alive retains a critique of the empty promises of capitalism, one that centers queer women instead of macho men. In place of fist-fighting, we get fisting. Instead of glorifying “poverty tourism” (Pemberton’s phrase for that sabbatical from middle class before eventually re-entering the fold), Still Alive exhibits an ambivalence toward the norms V is expected to follow. V doesn’t drop out like her brother, or like the men in Fight Club; she sticks around and white-knuckles her way through her cognitive dissonance. She may critique the system, but she doesn’t mind a comfy little house, designer clothes, or a fling with a “petite and beautiful and bossy” movie producer in Hollywood. If Fight Club touted moralistic dogma and material deprivation as a path to liberation, Still Alive laughs in the face of such naïve confidence in easy solutions. For V, nothing brings total liberation. But in its absence, we can find its approximation in friendship, a chosen family, and love.

Jason Christian is a writer based in Atlanta, Georgia. His essays and criticism are published at Bright Wall/Dark Room, Gulf Coast, The Los Angeles Review of Books and elsewhere, and he co-hosts the Cold War Cinema podcast. Find more of his work at jasonchristianwrites.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.