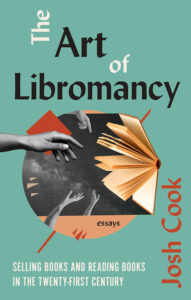

[Biblioasis, 2023]

In The Art of Libromancy, Josh Cook asks booksellers to live by their ideals. As a bookseller himself, at Porter Square Books in Massachusetts, he seeks to set an example for justice-based bookstores—justice for booksellers in their employment conditions, and justice as a motivation for bookselling. Cook’s ideal booksellers sell the books that they want to get out into the world, and they rely on their own storehouse of reading knowledge to go beyond bestsellers lists and media interviews. Cook’s ideal bookstore supports the interests of its community and offers a shared space. As I read, I wondered: isn’t this what a library offers? Libraries, too, are community spaces supporting multiple needs for their communities, including (among many other services) reading material that supports a wide range of interests at no cost, and in the best instances, gives people the opportunity to think and perhaps find their place in the world, regardless of which demographic factors define them to their benefit or detriment. Libraries, like bookstores, require a source of income to keep their operations running well and they both need a satisfied public to ensure that income. But, unlike bookstores, libraries only need to make ends meet—booksellers have the added burden of making a profit.

Across the essays in this book, most of which began as blog posts, Cook shares important ideas that he believes will help bookstores prosper, including ideas about how publishers can better support bookstores, the importance of agency for the on-the-floor booksellers, and the community role that a bookstore can fill. No one who frequents bookstores would argue with Cook’s assertion that bookstores and booksellers should raise awareness of new authors and perspectives. Cook does not advocate keeping books off the shelf, but he would like to see booksellers follow their consciences in deciding which books to highlight and which to tuck away out of prominent view. A bookstore is a private enterprise, one that can highlight and sell what it wants—its responsibility is to itself and, if the owner and staff are interested in more than just the profit margin, to their community. What reader wouldn’t love going into a bookstore where the staff remember them from their previous visits and pay attention to their interests, who know where everything is, and who know enough about the publishing world to be able to help uncover the book you read about but forgot to write down?

Cook describes three types of bookstores: the conservative bookstore, the radical bookstore, and the progressive bookstore. The conservative bookstore has an “amoral” approach. The staff put the books on the shelves and their primary motivation is sales—selling any and all books. The authors and publishers, regardless of their perspectives, are the voice of the store. The radical bookstore is designed around an ideology, whether promoting a certain religious perspective, environmental concern, the perspectives of a certain demographic, or a political viewpoint. Cook admits that there is a place for the “radical bookstore,” but he is arguing in favor of what he calls the progressive bookstore. In this bookstore, the booksellers take an active approach to promoting books they want to see read.

Something here doesn’t sit quite right with me. Cook prides himself on being able to sell the books he wants people to read. I’m sure I would love walking through Porter Square Books, but I think I would also feel oppressed if the bookseller was pushing Ellman’s Ducks, Newburyport on me when what I’m really looking for is a particular translation of the Iliad or the latest Donna Leon detective novel. I might like big books, but I might not like that big book. I like seeing a book displayed invitingly, and I might pick up Ellman’s hefty volume from a display table and peruse it on my own, but I don’t know that I would welcome a bookseller setting out to persuade me that I want to read it.

How does all this compare with libraries? Whether academic or public, libraries do not set out to support a particular perspective or voice. Librarians might have favorite books, but they aren’t going to persuade someone to read them. Instead, the librarian works to get the reader to the book they have in mind or are hoping to discover. Cook might see this approach as falling within the sphere of the amoral bookstore. And, of course, there will be librarians who have a strong idea of what they think people should be reading, but this is contrary to the way most librarians carry out their work, and it is, in fact, contrary to the American Library Association’s professional code of ethics. The code consists of nine values and includes the responsibility to resist efforts to censor books, to protect a library user’s privacy, to refrain from promoting one’s private interests at the expense of library users, to distinguish between personal convictions and professional duties, and to affirm the inherent rights and dignity of every person. You can imagine how some of these values might be quite hard to live up to with pressures coming from across the political spectrum. Librarians have criticized themselves for defining their approach as neutral, claiming that there is no neutrality. There is validity to this but, at the same time, if there is no neutrality, there can be no universally safe place—the space will be hostile to someone. I believe it is an impossible challenge to create a space and a collection where everyone feels welcomed.

We are in a disturbingly precarious position with free speech in the US. Attempts to ban books have risen and in recent months we have seen legislators and donors use free speech to successfully pressure university presidents to resign. Which free speech gets defended and which free speech is stifled? How much does power or status determine who makes the decisions? Does one person or one group of people get to decide which books are or are not available in a library or bookstore?

S. R. Ranganathan, an influential early twentieth-century librarian and mathematician, established five laws of library science. These are still valid today and might apply equally to bookstores as they do to libraries. They are:

- Books are for use.

- Every person his or her book.

- Every book (or document) its reader.

- Save the time of the reader.

- A library (or a bookstore?) is a growing organism.

Cook might describe the second law as “amoral” because there is no suggestion that there is a right or wrong book for any one person. But this law calls us to respect the intellect and diversity of desires and needs of readers. Cook’s wish to have the bookseller take the initiative with the customers can mean more than sharing an individual passion or set of beliefs if it leads to understanding the reader’s interests and through that understanding, helping them to the book they have in mind and making sure they can be more independent the next time around. This success and independence of the reader, student, community member is what the librarian strives for—every person their book, and every book its reader. The librarian or bookseller diminishes the reader’s agency if they begin their interaction with what they think the reader needs. Intentionally or not, they elevate their interests over those of the reader, and simultaneously lessen the reader’s chances for true, joyful discovery.

Of course, what the bookseller displays most prominently is going to affect who walks in the door. In the 1980s, I was never going to walk into a bookstore that prominently displayed the autobiography of Oliver North, a national security council staff member turned born again Christian who was involved in the Iran-Contra scandal. His book, front and center, was a sure sign to me that this bookstore was not the place where I would find community or a congenial place to pursue my own personal or intellectual interests. A library of that period may have displayed recently published autobiographies and included Ollie’s contribution to the genre—one among many. In that scenario, it is up to the reader to decide to pick it up or to ignore it. Librarians are all about discovery and access—we don’t make the decision for the reader. We want to get books into readers’ hands through guiding them in the different methods available for them to discover and identify what they want and need.

The book reviewer lies somewhere between the bookseller and the librarian. They know what they like, and they look for it in the books they read. Their job is to express an opinion and to make a judgement. They have developed a certain way of reading and created, consciously or through happenstance, a particular reading path that they communicate to their readers. Readers may agree or disagree. What they read in a review may help the reader to decide for or against the book. The interesting thing is that the very quality a reviewer highlights to recommend a book may be the very quality that turns the reader away, and vice versa. I used to write for a book review section of a journal intended for librarians. I think that the books I was excited about were outnumbered by those I didn’t find compelling. The books I didn’t like I reviewed more ambiguously, because I knew that my perspective was never going to be universal. My dislike of a book did not mean that it would not be a good read for someone else. Of the books I was reviewing, I rarely came across something that I thought had no business being in a library. I was aware that my own reading tastes did not match everyone’s preferences or even the preferences of most readers.

Where does the bookseller fit into a world of likes and dislikes, beliefs, causes, and missions? Cook would like the bookstore owner (and the publishers) to resist political opportunism and to avoid flagrant misrepresentation of truth, to mind their conscience rather than a non-differentiated drive for profit. Reeling from the multiple traumas of Trumpian politics, the January 6th insurrection, and the social unrest around Covid restrictions, Cook takes a close look at free speech, differentiating free speech from “absolute free speech.” He explores whether providing an environment for free speech also means a moral necessity to provide a platform for ideas that are flagrantly not true. Sharing opposing viewpoints through thoughtful debate can lead to change and compromise. It is hard to engage meaningfully with obvious falsehoods. Leo Strauss, among other thinkers, warned that to make a false statement true, one need only repeat it over and over again until it is accepted. Cook asks that bookstores, owners and booksellers, not be complicit with this repetition.

This brings us back to Cook’s belief in the power of the bookseller to use a variety of methods to advocate for the voices they want to elevate, to bring new voices to the attention of readers, highlight ideas they are passionate about. Cook imagines the bookstore as neighbor. He feels strongly that the bookstore can do what it takes to survive and at the same time, make decisions that improve the neighborhood and that even seep out to improve the world outside its neighborhood. It makes sense to empower booksellers who are also readers to provide insight into what to carry and promote. As independent businesses, bookstores can make their choices and readers can choose the bookstore that best meets their needs. I think this is where the library and the bookstore, the bookseller and the librarian serve different purposes. The library should be a place where every reader has their book and they are supported in the exploration for and discovery of that book. Ranganathan’s law can be adapted a bit for bookstores—every bookstore its readers and every reader their bookstore.

Rebecca Stuhr is an associate university librarian at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries in Philadelphia. Her academic background is in literature and music performance and her career as a librarian has centered on collections, outreach, and engagement. She has reviewed fiction and literary studies for several library review journals.

This post may contain affiliate links.