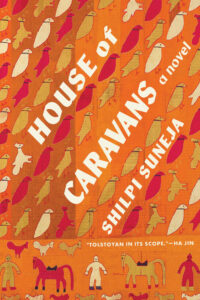

[Milkweed Editions; 2023]

Choose this, or that; live here, or there; love this person, or that one: false choices on offer by the specter of Authority. Shilpi Suneja’s debut novel, House of Caravans, follows three generations of a family resisting empire, as well as the choices empire foists upon them. One timeline in this intergenerational saga follows the years of 1943–47, the twilight of the British Raj, as anti-colonial resistance grows and the Muslim League demands their own independent state of Pakistan. The novel’s other timeline roots itself in August 2002, as Karan, older brother to Ila and part of the family’s third generation, travels from New York to India. He returns because his grandfather Barre Nanu has died, but also to escape the post-9/11, violent antagonisms alive in the City of Dreams. Suneja’s debut novel asks what it means to both belong to and resist categories of geography, religion, caste, and time.

House of Caravans also reminds us again and again that belonging has never been reducible to a simple choosing of sides.* Inter-religious, inter-racial, and economic relationships abound within the novel. And these intimacies are unraveled—often violently—when they come up against the broad sweep of history. Barre and Chhote Nanu are brothers who happen to live in Lahore, a majority Muslim city, though they themselves happen to be Hindu. Chhote Nanu falls in love with a woman named Nigar Jaan, who happens to be a Muslim woman of both Indian and English descent. Barre Nanu owns a cloth business and employs Muslim weavers to make uniforms for the British Empire. These entanglements—which electrify the entire novel—between colonial subject and colonizer, between Hindus and Muslims, between Pakistan and India, make legible the awful violence of Partition and the British colonial rule that preceded it.

No one is simply one thing, no identity so easily delineated into a neat box of religion or geography. But these entanglements encounter, sometimes fatally, a language and logic of belonging. As the frenzied violence of Partition bubbles, Barre Nanu stands in his shop with a Muslim friend and employee of his. Barre Nanu wants to believe that “Lahore belonged to Lahoris, Muslims and Hindus” and wants his friend Moin Bhai to agree. But Moin Bhai can’t. “It is not up to me, bhaijaan,” he says. “It’s not up to any of us. We are too small to matter. I only want peace. If that is achieved by you staying, you should stay. But if you have to move, who am I to say anything?” It is hard, amidst such violent reckonings—amidst a Partition of two countries that would claim the lives of a million people—to disagree with him. Later, Barre Nanu’s shop is burned to the ground, and he has to flee Lahore.

Even so, Moin Bhai demonstrates the power of individuals to change the course of history: he saves Barre Nanu from death. Suspecting his friend may be trapped inside his burning shop, Moin Bhai runs from his home to the shop with a spare burka in hand. He instructs Barre Nanu to pose as a Muslim woman, then finally hides him in his own home. Moin Bhai’s act of bravery gives Barre Nanu a new life after the fire, just as Barre Nanu himself had given Moin Bhai “a new life, a new skill” by hiring him in his cloth shop. Caught in the tentacles of circumstance, individual people perhaps are not too small to matter. We can save each other, even if the saving is predicated upon a simple piece of cloth wrapped around a head.

In New York City, along the 2002 timeline, difference and belonging boils down to simple appearances, too. Karan takes a Muslim friend of his named Meelad to the Hindu temple. Meelad wears a beard, which immediately marks him as both a threat and a target—an inversion of Barre Nanu’s burka, which led him to safety. “Bold choice, ciruvan, to keep a beard these days,” the head priest says. His comment strikes at the heart of the post-9/11 contradiction, where the perception of Muslims as a threat becomes the excuse to commit violence against them. The Hindu priest pulls Karan aside to tell him, “It might not be wise to bring your friend here. Or for you to keep a friend like him. Their mullahs preach jihad.” And the skepticism goes both ways. When Meelad and Karan eat at the Islamic Center of Flushing the next evening, Karan’s Hindi name is met with skepticism. The imam tells him, “You are welcome to eat here, Karan. But it would be best if you don’t participate in the worship.” The logic of belonging, which leads to the burning of Barre Nanu’s shop, the killing—during Partition—of a million people, the forced migration of tens of millions, is revealed as a bloody battle of appearances, a question of beards and burkas.

So, how to resist strict categories of belonging? Ila, the younger sister of the youngest generation, is the novel’s clearest theorist of resistance. She argues, along with Ambedkar—world-class administrator, anti-caste thinker, drafter of India’s Constitution—that people should “cut ties with your co-caste people to nip the power enclaves in the bud. All marriages should defy caste and religious divides. No more same-caste and same-religion alliances.” What Ila advocates for is the exact kind of entanglement and transgression that her family has been pursuing for generations. And because the two timelines of 2002 and 1943–47 are interwoven, Ila’s arguments appear alongside the actions of her mother Bebe, who marries and has a child with a Muslim man; Chhote Nanu, who falls in love with Nigar Jaan; and Barre Nanu, who has a child with a Muslim woman, that child being Bebe herself. This synchronicity honors the history of such transgressions and imbues that history with the urgency of the present. But the darker side of this effect is to reveal, in almost claustrophobic fashion, how little has changed in the way of religion and caste. When Karan is reunited with his long-lost father, who is Muslim, Karan learns that he has been living just “two lanes down” for Karan’s whole life. Two lanes but a whole world away, segregated by religion; Karan’s street is Hindi, his father’s is Muslim. And the continued danger associated with transgression, with entangled living, is clear: as Karan and his father talk for the first time, they are interrupted by the sound of shattering glass outside, as a procession of supporters for the Hindu party announces through a megaphone: “Muslim friends, you belong in Pakistan.”

Ila claims in a conversation with her brother Karan that “there is no such thing as India. It only exists in the dreams of foreigners like Columbus or Dickens or whomever.” And yet, the juxtaposition of timelines in House of Caravans complicates her argument. The novel reflects a closed circle of tragedy, a prison with no way out, where characters hold onto these categories for dear life, or death. And the closed circle reveals how claims to national identity will always be a dead-end, a snake eating its tail. If one’s safety and prosperity is built upon the exclusion and precarity of another, then that safety will always be short-lived, crumbling on a dead and cracked foundation.

The very structure of Suneja’s novel shows us that entanglement and transgression are the way out. Though the procession threatens violence, Karan and his father go outside, cross the neighborhood line, and return to Bebe’s home on the Hindu side of the neighborhood. Karan looks at his father as they walk and realizes that their neighborhood was created by “a million little decisions to coexist. To carry the weight of a smile, to negotiate small spaces and tight corners.” And the logic of that kind of living, of coexistence in close quarters, is love. “Only love operated that way,” Karan thinks. “Hate shot like a spear, but love spread as a cloud.”

Love spreads across the sky like a cloud, irrespective of geography, its logic itself transgressive. “Maps had cruel hearts,” Karan thinks at the end of the novel. He wonders instead what living might be like “if only we could make our home in a season, point to a season instead of an address and say, this is where we live.” Karan situates love, liberation, and freedom alongside a temporal rather than geographical dimension, thereby refusing the “India” of white, foreign men’s dreams. Geography, after all, is what tears people apart throughout the novel, where people make claims to belonging based on religion or caste. Karan refuses the false binary, seeking a capacious sense of belonging that excludes or silences no one. And as each generation of his family has done before, he makes a commitment to transgress, to entangle himself. He decides to go to Pakistan, to Lahore, where Barre Nanu and Chhote Nanu were born and raised and were forced to flee. In Lahore, Karan hopes to reclaim not a geography but a history, the memories of his grandfather, his great-grandmother. Reclaiming this timeline is not only a historical liberation but an act of love. Karan knows what he is up against. That same logic of belonging might delay their visas, “or [the visas] might be denied entirely.” Still, he “had to try. [He] had to make the first move.” The circular tragedy Suneja draws in this intricate debut is perhaps not a circle at all, but a spring, ready to burst as soon as we allow ourselves the freedom to love across borders, rooted not in geography but in time.

Gus O’Connor is a writer currently based in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

*After Bruce Robbins’s Criticism and Politics: “Politics has never been reducible to a simple taking of sides.”

This post may contain affiliate links.