[Pilot Press; 2023]

John Wieners ends his 1960 letter to Barbara Guest from inside psychiatric incarceration with an appeal to togetherness: “Pray for my freedom and we shall be kind enough to find release in each other’s arms again.” Included in a new collection of Wieners’s work, Solitary Pleasure: Selected Poems, Journals, and Ephemera, this letter accentuates solitude rendered by Wieners’s poetry as something different from aloneness. Earlier in the letter, he asks if Guest will be a part of “the New Measure”—the third issue of Wieners’s journal Measure—where he also publishes poems by Helen Adam, Jack Spicer, Larry Eigner, among other figures of post-war American poetry. His writing emerged from a need to be with those from whom he was often separated. Even in moments of enforced separation from society, memories of Wieners’s friends, lovers, calls for their work, and hopes for their reunion echo in the poet’s mind and on the page. With a thorough presentation of the contexts that surrounded Wieners’s work, a figure of the poet emerges in Solitary Pleasure as one often isolated from—but not lacking in love for or influence from—his friends, compatriots, and communities.

Wieners was active in the gay liberation, anti-war, and mental patients’ liberation movements and experienced five psychiatric incarcerations between 1960 and 1972. Born in Milton, Massachusetts in 1934, he studied under Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, and Robert Duncan at Black Mountain College between 1955–1956. After brief stints in San Francisco, New York City, and in Boston working as a department store subscriptions editor, Wieners enrolled in SUNY Buffalo’s graduate department, where Olson was a professor. In 1970, he moved back to Boston, where he continued to publish poetry and involve himself in political organizing and activism. He lived on Beacon Hill until his death in 2002.

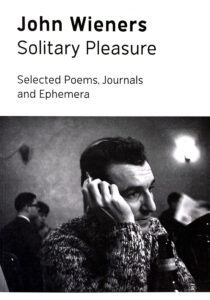

Solitary Pleasure includes three sections: a selection of “classics” and “deep cuts” from 1952–1970; a reprint of Wieners’s Asylum Poems, written in the summer of 1969 from inside Central Islip State Hospital; and a selection of ephemera, letters, journals, and previously unpublished materials. The collection is edited by Richard Porter and includes an instructive introduction by Nat Raha titled, “Types of solitariness (against the asylum).” Raha introduces “John ‘Jackie’ (occasionally ‘Jacqueline’) Wieners” as “a working-class, gay/bisexual, Mad poet with femme and sometimes trans sensibilities.” Wieners was in a psychiatric hospital, undergoing conversion therapy and writing Asylum Poems, while the Stonewall Riots were happening. “Times Square,” the shortest poem from that pamphlet, reads just three lines, “a furtive queen / hurrying across a deserted thoroughfare / at dawn.” Poets, artists, and scholars like CAConrad, Michael Seth Stewart, Robert Dewhurst, and Joshua Beckman have given new life to his work in recent years, but Solitary Pleasure stands out as a collection that centers Wieners’s charming poetic spirit in the face of sexual and medical marginalization.

The imagination breathes deeply and urgently in Solitary Pleasure. Many pieces dwell in the confined space of the self but invoke friends, lovers, other poets, and figments of the imagination. The poem “Memory” states, “Poetry is a desperate act / the last-minute decision / against self-annihilation.” More playfully, Wieners’s journal entry from Wednesday, the 26th reads, “I hope to get to the Poetry Center while I am in the ‘white and glittering’ city . . . feeling somehow devoid of thought today. I would rather go off and read Pound’s poetry in a corner, or listen to Bizet.” This entry then becomes a page-long “story running over and over again in my mind concerning a man who rides the swan boats. These hold the same fixation for him as alcohol or sex would to another.” Wieners’s writing makes music out of getting lost. Winding, circuitous routes map his speakers’ thoughts, but his subject matter is not solely imaginary. The poem “Charles Olson” plays at being a letter to Wieners’s friend and mentor about a visit to a beach. Its tender depiction of time with friends, “the 3 / of them slept around me, wrote poems about it, their breath- / ing. It was enough,” reveals his exact attention to emotion. On this note, Robert Creeley calls Wieners, “the greatest poet of emotion,” and says that his poems, “had nothing else in mind but their own fact.”

The collection’s second section, “Asylum Poems,” has a voice replete with peculiarities and an idiosyncratic sense of time and measure. Written while Wieners was in forced psychiatric incarceration, the pamphlet confronts readers with the reality of the mental hospital as a disciplinary technology wielded against poor people, drug addicts, and sexual minorities. The poem “Private Estates” concludes, “No, the wild tulip shall outlast the prison wall / no matter what grows within,” a stirring invocation of beauty in the face of institutionalized violence. Raha discusses in the introduction the “regimented and excessive use” of insulin shock treatments that Wieners underwent and other forms of conversion therapy in place at the time, including electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Wieners said these treatments destroyed his memory. His poems, at times dwelling in a remembered past, nonetheless convey an amnesiac quality, describing suprasensory imaginings inside what feels like a permanent and undifferentiated present.

Formally, the poems’ spare use of end and internal rhymes—occasionally at the cost of sense—project the poems into a realm of fantasy, memory, and childlike daydream. Part 2 of “The Dark Brew,” the opening piece in “Asylum Poems,” playfully uses rhyme to evoke its reverie:

Ah there the haven lies in some sweet vision of your collapsing purple / amethyst eyes? / within a face not mine to surmise, ring with outshooting apple blossoms / Oh, who knows the look of false surprise.

Here, Wieners’s typically fragmentary, angular lines resolve into melodious, sing-song lyrics. These qualities and the inconsistent capitalization and punctuation recall something of Emily Dickinson’s queer grammar. In “Removed Place,” a haunting depiction of forced isolation, Wieners asks, “When the shadows enlarge, will one / enter it or stay where / he is now. What will one do, how.” The smallness of the poems crystallizes the claustrophobia instilled in their oblique images and stark interrogations.

Wieners’s life in Boston alongside fellow poets and lunatics Stephen Jonas and Jack Spicer is also legible in the works collected in Solitary Pleasure. Jack Spicer only lived in Boston for a short time but notes of that poet’s “uncomfortable music” ring in Asylum Poems. Wieners’s poem “High Noon” reimagines characters from Arthurian legend to articulate queerness: “Another silver Iseult / joins svelte Tristan / down a vault of tears.” Later, in “Melancholy,” Wieners returns to Tristan’s and Iseult’s dalliance and associates the speaker of the poem with Iseult. Following five couplets in third person, the poem’s final lines, “sturdy lass I’ll be for there, / and faint-hearted song you’ll whisper,” are directed to a masculine Tristan. Spicer’s Holy Grail performs similar allusions. Pilot Press has also recently released a new edition of Spicer’s posthumously published collection, A Book of Music, showing the press’ commitment to republishing out-of-print and hard to access works of midcentury queer poetry.

The Boston poet Stephen Jonas was also plagued by solitariness throughout his life, but his poems perform a different alchemy than Wieners’s. Collected in City Lights’ A Stephen Jonas Reader, Jonas’s poem “For John Wieners 1/6/60” describes his friend’s style as, “you . . . / sound / like a black iris by Kline / a broken telephone / (old kind with horizontals / and forks receiver.” The date in the title suggests this poem was written close to one of Wieners’s lengthy psychiatric incarcerations in 1960, elucidating the later lines, “why / hell noe / suffer there for me to / suffer. / whats? / if this music hits you hit / back.” Both poets struggled through isolation and addiction. They both shared an interest in magick and the occult, and used Tarot in their poetic practices; however, their poetries reveal two different relationships with solitude. Wieners’s poetry carefully measures out the space allotted to their solitary musings, whereas Jonas’s frantic line breaks and propulsive exclamations refuse to stew in their loneliness. Both their poetries are surrounded by imagined voices and presumed interlocutors, but Wieners’s perform an obtuse and unflattering zero-ing in; they’re microscopic and minute, while Jonas’s sprawl, jibe, and fall diagonally down the page like a clattering of hallucinations.

Solitary Pleasure’s final section of miscellanea includes scanned images of the Summer 1973 issue of the Boston gay newspaper Fag Rag, showing some of John Wieners’s contributions. A small poem, tucked into the gutter of the reprint, titled “The Loneliness,” begins, “It is so sad / It is so lonely / I felt younger after doing him, / and when I looked in the mirror / my hair was rumpled.” Solitary Pleasure brings together pieces of writing that emanate queer loneliness and longing, allowing the desperate, the embarrassing, and the delusional intrusions of a solitary mind into the art of the poem. His writing retains a lightness and charm during their occasionally depressive musings. A review in Fag Rag praises Wieners’s writing, “John brings a light purity, passion and love out of a ‘camp’ sensibility” and says, “the immense quality of love (care) in John’s commitment to people, life, the world, everything around him is everywhere evident.” Rather than a self articulated by its limits, Wieners presents a self made manifest in its desire for the other.

This new collection, while highlighting the singular voice of one of America’s preeminent queer poets, contains documents of John Wieners’s enduring multiplicity. His careful interrogation of self leads readers into a web of friends, lovers, and poets who touched his life, facing outward towards the world, unafraid and uncompromising despite the violence repeatedly inflicted on him. His struggles were collective even as his writing emerged from isolation. When asked in a 1974 interview with Robert van Haberg whom he writes for, Wieners responded, “for the poetical, the people . . . Not for myself, merely.”

Joe Rupprecht is a poet living in Oakland, CA. His work can be found in Dream Pop Press, Spoon River Poetry Review, The Poetry Project Newsletter, The Cackling Kettle, Heavy Feather Review, Petrichor, SORTES, and elsewhere. He tweets @heterofobe.

This post may contain affiliate links.