With the publication of You Shall See the Beautiful Things (Acre Books, May 2023), Michigan-based author Steve Amick returns with his third novel, inventing a narrative style all his own. This imaginative, exuberant tale re-tells the famous fantastical verse of Eugene Field’s “Wynken, Blynken, and Nod.” At the onset of the narrative, the reader meets the three distinctive characters—Wynken van Winkel, an irreverent opium addict gone AWOL; Ned Nodder, a narcoleptic fisherman; and Luuk Blenkin, an impressionable young wannabe singer—as they move between large bodies of water and land, waking life and dreams, reality and unreality. Part fairy tale, part nocturne, part literary sleight of hand, Amick’s expansive historical narrative delights and challenges the reader in the very best way. “Every page is filled with marvelous revelations about the nature of the world and about being human,” praised Bonnie Jo Campbell, author of Mothers, Tell Your Daughters: Stories. “Here, despite the weight of colonialism, war, and financial and family struggles, folks with open hearts can still find magic and goodness, can still live lives ‘mostly full of awe.’”

Though Amick and I are both native Michiganders, we met at a small liberal arts college, St. Lawrence University, in the remote town of Canton, New York, in the eighties. Though we didn’t know each other well, Amick played in a popular college band called The Angry Neighbors with some of my mutual friends, who frequently performed at the local haunt called The Hoot Owl and the basements of fraternities. Many years later, Amick and I reconnected when I published my debut novel, The Elephant of Belfast, in April 2021. Now I live in Austin, Texas, and Amick spends a good deal of time at his recently built cottage (which includes a bathtub with a view of the falling snow during the winter months and where the author does a lot of his writing) in Manistique in the Upper Peninsula. During the month of November, we corresponded via email for the following interview about the dazzling You Shall See the Beautiful Things—the inspiration for this singular novel, his daily writing process, the interplay of music and writing, and the importance and appreciation of large bodies of water.

S. Kirk Walsh: What was the initial inspiration for You Shall See the Beautiful Things?

Steve Amick: A literal fever dream. Later, my doctor decided I had an early case of the H1N1 swine flu, which became a pandemic a little later that year, in 2009. I had the shakes and chills and was trying to ride it out lying on the stone hearth in front of a roaring fire. I write every day, even the day my son, Huck, was born and the day I got married. It’s often crap or nonsense, but at least I show up. So, I was scribbling in my notebook, with my face on the floor, and it may have been a need to feel comforted or reassured that led me to essentially a lullaby. I suspect I had a little glimmer of fear that I was really sick, that it could even be fatal.

I started thinking about nursery rhymes, at first, considering whether there were some that hadn’t been reinterpreted in a way that invests them with more reality or gravitas, and I was drowsy and nodding in and out, which probably was how I landed on “Wynken, Blynken and Nod,” and this whole idea came to me and I scrawled out two or three pages of the basic idea. Not knowing anything about herring fishing, or the Dutch, etc. Not even really recalling all the parts of the poem. But the idea was there—take each line of the poem and have it shape the story, thematically, by the phrases in the line, regardless of chronology. Don’t make it a literal translation of the poem, just use each line as a jumping-off point. The whole complicated construction was there. Obviously, I had a raging fever and was delirious. But then, when I got better, I found it in my notebook, and it didn’t seem THAT crazy.

When did you first discover the children’s story “Wynken, Blynken, and Nod” by poet and writer Eugene Field? Do you remember the first time that you read it?

I’m not sure. I don’t think we had a Field book at home, though the N. C. Wyeth illustrations now look very familiar. And my grandmother had a book with the Calico Cat in it—another Field verse—so maybe she had the whole collection at her place. . . . But what I really recall is a cartoon version, possibly Disney’s Silly Symphony version, which I definitely first saw on Captain Kangaroo with Bob Keeshan. He had this weird little TV screen behind his counter, and he’d occasionally show something pre-packaged, as filler. I remember very clearly watching the cartoon version on his show.

What about the role of punctuation in the narrative? How does it define your trio of characters?

In terms of defining the characters, first, it wouldn’t be my practice, generally, to have the three characters speaking in first person. That just adds a level of psychological filtering and unreality that I find problematic and usually contrived. But in this case, I wanted the rhythms to feel like the poem, too, so that cut into my ability to have all three characters have really distinctive diction. I did that with The Lake, the River & the Other Lake—gave each character such a distinctive voice that even though it was in third person, I was told by many readers that you could open it up and know straight away whose section you were in, just based on the voice of the section. I knew with this book I also wanted you to know which of the three men was the star of each little section. But I also wanted the language to be slightly stylized, so that it had some of the same rhythms as the Field poem, and the Edward Lear poem, and to be sort of rhapsodic about the night and the sea and all that, even feel a little otherworldly.

Yet the characters are very different personalities, so I cheated that distinction some with the punctuation. Ned Nodder, who has the sleeping disorders, but is also very agreeable—lots of “nodding”—his passages are stuffed with ellipses. He’s a narcoleptic. The nineteen-year-old wannabe troubadour, Luuk, is very scattered. He basically has ADD, so his passages—again, though written in third person, they represent him—are just a mess of disjointed sentences, cut by em dashes. And then Wyn, who makes sly comments and asides, but also keeps things close to the chest, speaks out of the side of his mouth, in a way, so half of his stuff is muted behind brackets. It’s a way to let the reader in while still indicating he’s not really letting others in.

The dingbats at the start of each section were the brainchild of the editor, Nicola Mason, and her designer, Barbara Bourgoyne. It was a way to further ID each section without resorting to the names. Wyn, who’s a wanderer, has sections marked with a compass star. Ned Nodder, the “old man,” is a man in the moon, tying him to not only the moon in the story but to sleep, which he has such medical problems with. And then Luuk is a dark cloud, for his worries and concerns, but it’s also moving, caught on the wind—the constant shifting of his thoughts and concerns and ultimately, his restlessness.

The third typographical “trick,” I guess, is the headers. I think this is lost on Kindles, and so I wouldn’t advise reading it that way, but it was important to me that the line from the poem that informs each section be constantly visible as a header on each page.

Could you talk a little bit about the process of writing this novel—how you lost the file and then started writing it again several years later?

I worked on it on and off for a couple years, backburnered from some other projects, and then in 2013, my computer crashed like the king of all crashes—nothing was salvageable. And I hadn’t backed it up. I had maybe forty to seventy pages of a Word doc, and I assumed I must have certainly at least printed them out, but I couldn’t find them. I stopped worrying about it and figured I’d find it one day. All I had was the sweat-soaked few pages from my notebook, notes from the original idea.

Then in March 2017 we had a storm that knocked out most of the Midwest power for most of a week and I tried to think of something I could work on on notepads with candlelight and no real need to look up stuff on the computer, and I remembered the “Dutch book” and found the old notebook—just the three pages of initial notes—and started over from scratch. And then when the power was restored, I moved into the bathtub—I have a tub desk I built—and finished the whole thing in the dark, soaking in water. I think it made a difference. It certainly allowed me to let loose of the constraints that normally would tell me it was too weird or it wouldn’t work. It was very dreamlike, the whole experience. A candlelit tub is like a time machine—darkness can be a form of time travel, I find. All those modern trappings get shed away.

Could you talk about the intersection of research and writing with this novel?

It required research to keep going, and to finish it, but not to get it started. I tend to write with big gaping holes where I know something is happening, vaguely, but I can’t quite see it yet, so I can get going pretty easily with very little information.

The book got set in 1889 just because that’s also the year of the poem, and because of that, once I had a time frame, and started learning about what was happening then and the biggest discovery, for me, was the Aceh War, in Sumatra. I was bowled over by the similarities to our own more recent military conflicts, including a lot of the same type of aftermaths.

And what was one of your most surprising resources?

One thing that’s fantastic is that the local painter from the era of the story, Henrik Mesdag, painted this massive panorama, within that same decade. It took years, but it’s a 360-degree canvas of Scheveningen Beach, with all the bomschuitten, the herring boats, on the beach, and the boardwalk that’s in the book, the Strandweg, and the big solitary hotel, The Kurhaus, and then back to the church spires and taller buildings to the east, in the heart of the Hague. And it’s now on display right where it was painted, in a circular building. And once I saw that, it became effortless to transport myself to that place and time.

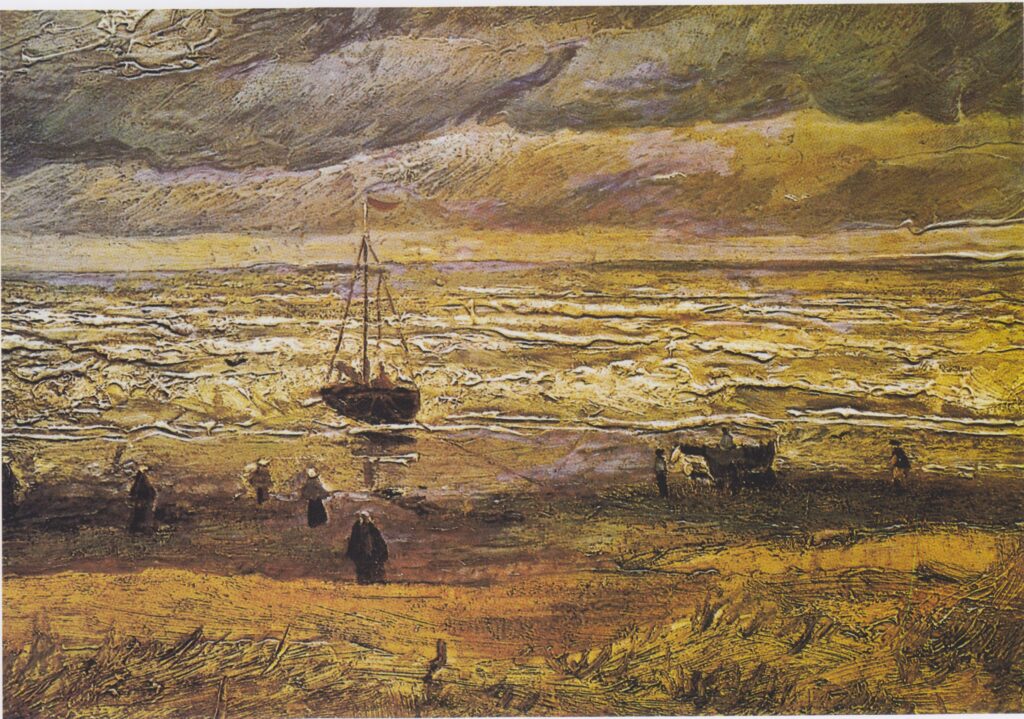

The paintings from that era, mostly of the beach there, were very helpful to get the massive exertion it must have taken to operate those huge clumsy fishing boats. The stolen Van Gogh painting of Scheveningen Beach is one of those. Fortunately, the image still exists online, and you get a sense of the dark storms coming in off the sea and what the herring men were up against.

There are a couple websites that are dictionaries of Dutch language oaths and idioms—not the common Berlitz stuff, but weird figures of speech and insults, like klootzaken, which technically means “testicles,” but is used more like “assholes/dicks.” Someone who is a klootzak is just a real dick. I used that.

The Clovelly picarooner! That’s a real sailboat, unique to the fishing village of Clovelly in Devon, England. I had to dig online but finally found a diagram of one. And the videos of these things skimming along, trailed by dolphins, are just breathtaking. All this stuff was vetted later, of course, by actual individuals, especially the Dutch language. But it was fun discovering stuff and not feeling a ton of pressure to include it, so I could just use it if it spoke to me.

Did the landscape and water of Northern Michigan influence this book?

That’s always been a muse for me, in general. This book really stands out from everything else I write in that it doesn’t directly connect to Michigan—well, not overtly. Not seemingly. But both Michigan and the Netherlands are very water-based lands—meaning not just the Great Lakes, but the more I learn about my home state, the more I’m aware of how enmeshed in riparian tributaries we are. That’s very Dutch, the way the water is all connected throughout the landscape. But I think I did draw on my lifetime of standing on the edge of big water and wanting to slip into it. (I also am drawn to heights, so the combination is perfect for this book.) There are these studies that show most people react psychologically to moving bodies of water—some people more than others. I’m certainly one of those who are calmed by it. I become reflective around it, even if it’s too cold to go in. Growing up, my mom considered me her “water boy,” among the siblings. It not only calms me but enlivens me. Focuses my mind. And the lake cottage has always been where I get a lot of work done. The lake is such a spiritual place for me, that when my siblings got greedy and decided to sell the old family place, I was just brutally devastated. I’ve built a new place way up in the Upper Peninsula, on Lake Michigan, and I’m starting to feel normal again, but my wife said it was like a part of me died when I suddenly didn’t have that water in my life.

Anyway, that’s all due to the water-centric nature of our state. And because I’ve never actually been to the Netherlands, the water aspect of the place was something I felt I could really connect to, so that I could see it clearly as well. And I do think the water there also affects their national personality—all those dams and dykes and concerns about the encroaching sea. It must.

How does being a musician inform—or shape—your fiction writing? And this particular novel in terms of the form of a “nocturne”?

I know that when I write songs, I tend to see the construction of them in terms of shapes, representing verse, chorus, bridge, etc.—an unconscious visual sense of organization, and it’s very much the same with fiction, especially stories. I’m not saying I make plot outlines, but a sense of the structure appears in my head as I’m working on it and it’s shape-based in that same way. In this book, at the risk of using that trite jazz metaphor, it is a little like that in the construction, in that its built on just riffing on small phrases, like when you compose a piece that’s built around variations on a small musical phrase.

As for the nocturne, maybe my insistence that that’s what this was, a bit of apologia out of fear that it might not be “about” enough—fulfilling the expectations of form for a novel. But even with the musical form of the nocturne, in a way, to me, it doesn’t end up being so much about the night itself as about how we feel at night. I write at night almost exclusively and I actually don’t sleep till dawn, and some of that is the seclusion. You go stand out in the yard and look at the moon and it could be any year, pretty much. And so, in a musical nocturne, that’s the sort of thing I hear. Fears, isolation, emotion—some positive as well as a sense of loneliness. I think a nocturne is really about visiting these slightly dark thoughts and the conduit to doing it is nighttime.

Are there any authors, or particular books, that you feel like this novel is in conversation with?

To be honest, in a weird way, it’s sort of in conversation with Edward Lear’s poem, “The Owl & the Pussy-cat,” which isn’t really an answer because they don’t explicitly fish, and in a way that’s cheating, because this poem is also referred to in the text, though the story isn’t following each line of it as it is with the Field poem. But the owl and the pussy-cat do sail way off to the land where the Bong tree grows, which is an actual tree, but sure sounds like Sumatra, doesn’t it?

S. Kirk Walsh is the author of The Elephant of Belfast. Her essays, book reviews, and interviews have been published in The New York Times Book Review, Texas Highways, Longreads, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and other publications.

This post may contain affiliate links.