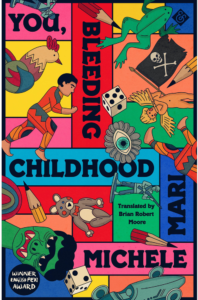

[And Other Stories; 2023]

Tr. from the Italian by Brian Robert Moore

In his house in the country, he still had all of his old childhood beds, lined up in the same room like an allegory of the ages of man—and should he not have conserved as sacred the first works he’d read? Were they not perhaps a document—proof!—of his childhood and, at the same time, of his anguished struggle to never leave that childhood behind, while the world, seemingly out for blood, had been plotting all along to tear it away from him, bludgeoning him with fears, with horrendous itches, with ambiguous intellectual conquests (The Epic Reawakening! The Way of Man!), blindly doling out blows?

Here, in a nutshell, are the landscape and mood of You, Bleeding Childhood, the first book by acclaimed Italian author Michele Mari to be translated into English. This collection of autofictional short stories is a heartfelt tribute to childhood. Celebrating the enchantment of those first toys and books, the collection is imbued with a sense of wonder and adventure, threatened at every corner by the harshness of adulthood and the looming fear that soon it will all be lost.

The collection of stories features a boy, Michelino, who spends endless summers in a countryside villa near Lake Maggiore with his grandparents. He is an introvert who likes to draw and assemble enormous jigsaw puzzles. Instead of going out to play with the children of the overly friendly and loud Baldi family, he prefers spending hours indoors, reading comics, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century adventure books, and Urania sci-fi paperbacks—a wide collection that calls to mind Yambo’s library in The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana by Umberto Eco.

With a few masterful strokes, some of the stories introduce the author’s father, the industrial designer and artist Enzo Mari. As an intimidating figure who is mostly in the background, he nonetheless instills in the protagonist an excruciating—and therefore comical—sense of guilt for losing or getting rid of some of his beloved toys over the years. “If you have twenty toys and you hold on to eighteen, you’re already toast. A certain pocketknife with a mother-of-pearl handle, a single red enamel magnet, as soon as you push them aside, however lightheartedly (‘Stay here for a bit,’ you say affectionately, as you tuck them away in a drawer), that’s it, you’re toast. You’ve become a squanderer,” he says to his mortified adult son in “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.”

The mother, children’s book illustrator Iela Mari, appears in “Jigsawed Greens” and “War Songs.” In the former, she teaches her son how to puzzle with method, embarking on a six-year-long “school of rigor” that, practiced with consistency, morphs the act of puzzling into “an animalistic source of pleasure.” For Iela, the only puzzles that are worth completing are pictorial, with the added benefit of indirectly teaching art history to Michelino, while photographic subjects are considered close to abominations. Five thousand pieces are a minimum for the two skilled puzzlers, who rapidly climb to new heights reaching 12,000 piecers. Immediate disassembly after completion of each puzzle is a must as a reminder of the complete gratuitousness of the whole operation, like a Buddhist practice that purifies and elevates the spirit of the practitioners. In “War Songs,” we learn that Iela used to sing the songs of the Alpini, the Italian mountain infantry corps, to the narrator when he was a child, inspiring his already lively imagination with images of mountains and heroic suffering; most importantly, he is also haunted by the body of a dead captain cut into five pieces, which will intrigue him for years to come.

Among the most vivid portraits of You, Bleeding Childhood, it’s impossible not to mention the delicate presence of Flora, a neighbor celebrated in the longest and final story of the collection, “Eurydice Had a Dog.” The old lady lives in a cottage that seems suspended in time and owns a seemingly immortal dog called Tabù. Michelino finds peace and comfort in visiting her and cuddling the little mutt. Staying with them is magical, but of course annoying disruptions to the idyll abound.

City life, on the other hand, is much more complicated, particularly when it entails facing off threatening classmates or hanging out at the playground. As the narrator in “The Horror of Playgrounds,” which shows poor Michelino dealing with the insidiousness of this space, says:

There is an area, right beneath the knees of young boys, that encapsulates the horror of playgrounds: there, where the skin is grayer and thicker, almost cooked from rubbing against the grass; there, where the grime has consubstantiated with the dermis. In those livid strips of hide are united all the disjointed undertakings of premature virility, the enrollment in organized mini-mobsterism, and the disgusting logic of the street.

The playground is crowded with “gangs of aggressors” prone to spitting all over the place and strangely socializing moms that, nonetheless, are a “guarantee of order and legality.”

All the stories—eleven from the original collection Tu, sanguinosa infanzia (1997) and two from Euridice aveva un cane (1993), which were added at the end of this English edition—organically converge to illustrate the many facets of the author’s childhood through a skillful alternation of literary genres, ranging from horror to suspense, comedy to adventure. The collection is not only tinged with melancholy due to the passing of time and the inevitable losses that come with it, but also enlivened by an irresistible sense of humor that elevates self-mockery to an art. It is hilarious reading about the author’s obsession with preserving his “sacred things” to the point of even hiding them away, fearing that his future child will want to play with them one day (“Comic Strips”).

In You, Bleeding Childhood, the multitalented Mari (novelist, poet, essayist, academic, translator, cartoonist) puts on full display his style that is simultaneously rich, experimental, literary, and playful, reminiscent of the technique of some of the greatest Italian writers of the twentieth century: Carlo Emilio Gadda, Giorgio Manganelli, Paolo Landolfi, and Alberto Arbasino. Metaliterature triumphs in “The Covers of Urania,” an inspired ode to sci-fi books of the 1950s and the 1960s, and “Eight Writers,” which reunites Mari’s favorite adventure book authors, including Daniel Defoe and Joseph Conrad, in a memorable dialogue. Last but not least, “The Black Arrow” celebrates the art of literary translation. Michelino is excited because his father shows up one day unexpectedly in the country and has a present for him. There is no greater joy than this surprise until the boy realizes that Enzo brought him a book that he had already read. He is so afraid of disappointing him that he doesn’t dare to tell him the truth. On the other hand, he feels terribly guilty for lying. When all seems lost, he has a sudden epiphany. The two books have the same title because they both originate from Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel, but are in fact two different Italian translations of the book. By comparing the beginning of the two editions, the ingenious nine-year-old reassures himself that all is good now, while readers delve into the pleasure of semantic analysis and recognize translation as a creative act.

Needless to say, this collection is a tour de force for translator Brian Robert Moore, who cleverly renders the baroque style of the original and, when needed, collaborated with the author himself “to keep elements of anglophone literature legible and coherent when translated back into English.” The result is convincing and exquisite. It speaks emotionally and intellectually to the readers, bringing us back to both beloved and scary times of our childhood while surprising us with the inventiveness of its language. From cover to cover, this book is a marvelous way to introduce Michele Mari to the English-speaking world.

Michela Martini is a literary translator from English into Italian and from Italian into English. Her translations have appeared in numerous journals and volumes, including the Literary Review, Poetry International, Gradiva, Catamaran Literary Reader, Chicago Quarterly Review, Journal of Italian Translation, Italian Poetry Review, and The FSG Book of 20th-Century Italian Poetry. She splits her time between Italy and California, where she co-founded and directed the Dante Alighieri Society of Santa Cruz.

This post may contain affiliate links.