[Duke University Press; 2023]

In February 2007 Britney Spears shaved her head at a salon in the valley. Frantic paparazzi pressed their lens against the salon’s windows to snap the now iconic photos of Spears wielding electric clippers. I first encountered these images on the pages of a gossip mag at work. Between classes at the university, I worked part-time at a Target Portrait Studio in Atlanta, snapping photos of kids and pets in their Sunday best. Company policy banned us from reading books or doing schoolwork during downtime, but we could read magazines the store sold. Books intimidated customers who might hesitate to interrupt us if we looked busy. Every day after I clocked in, I’d grab an armful of periodicals from the metal racks, Vogue and Architectural Digest tucked under my arm alongside Us Weekly and Star. In my red kiosk, I flipped through spreads of blue and white Nantucket cottages and exposés of celebrity affairs. With time I stopped thumbing the Conde Nast rags altogether, and instead, consumed a steady diet of tabloids, hits of scandal and exposure that helped me make it through my shifts. That spring, I immersed myself in the world of celebrity DUIs, drug scandals, and disheveled street snaps. At the time, I believed exposure was a net positive. Exposure broke down barriers between people with and without power and money.

It was while reading one of these tabloids that I discovered a truth about myself. The article was titled “My Escape from a Sex Cult,” a first-person narrative penned by a former member of the cult Children of God, also known as The Family. The author described cramped rooms in foreign locales, wine-soaked sheets, forced bible memorization, and years of routine sexual abuse by David Berg, the group’s founder, and Karen Zerby, the future leader. The language the author used to describe the group struck me: The houses where members lived were called “colonies”; the women who earned money for the individual colonies through sex work, “Queens”; and the group’s relentless proselytizing, “fishing for souls.” All were phrases my mother had used to describe what she referred to as her “commune life.” The stories she told throughout my childhood about her time at the commune were pleasant: She lived in a tent. She learned how to cook with wheat germ. She birthed me at home with the help of other women in the group. Nothing about her stories screamed sex cult. So I dialed her number. I coached and coaxed. She eventually confessed: “So what? I was in the group, but it’s not what you think. There were bad times but many more good times.”

Sixteen years later, my mother’s story about her “cult years” remains the same. “My time with them was happy. Better than my life before,” she says. Steeped in the early 2000s culture of personal essays and celebrity exposés, her stories of “good times” did not satisfy me. I spent the next decade researching The Family. I interviewed her and other former members, eventually writing a string of essays about the group. Through my research, I discovered extensive documentation of abuse, though members’ experiences varied. My mother’s version of events annoyed me. I wanted the truth—by which I meant the dirt—not only about her time with The Family but also about whatever life she led before joining that made life within its confines seem dreamy. Because I believed I was entitled to know everything about my mother’s traumatic past, I never thought to question what else I was missing by failing to listen and absorb her story as her story.

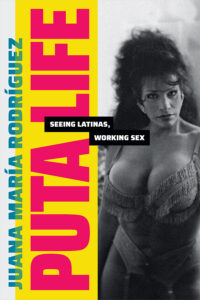

I had taken it for granted that my impulse to know was pure. Not until I read Juana María Rodríguez’s newest book, Puta Life: Seeing Latinas, Working Sex, did I begin to reevaluate my mother’s approach to storytelling as well as my own desire to uncover her past. Rodríguez, a Cuban-American professor of Ethnic and Gender Studies, writes about the intersections of race, sexuality, and violence with an electrifying blend of vulnerability and explicitness. Roving between the archive and the street, Rodríguez brilliantly charts the creation of the figure of the puta in the public imagination. Puta Lifa is also an unforgettable testament to the power of self-representation. It changed not only how but also why I write about history, trauma, and sex work.

As a word, puta has legs. The term traverses linguistic and geographical barriers, and its meaning is always in flux, changing as it circulates. Inherited from old Spanish, puta’s origins in Latin are unknown. Its most accepted translation is the English word whore, and it continues to be used as a slur to shame people who practice rebellious forms of sexual expression, particularly women of color. By weaving together archival documents with interviews, memoirs, and personal experience, Rodríguez explores the disparate meanings and representations of the slur throughout time. Beginning in the archives, Rodríguez traces how the puta came to be seen as a public figure in the first place, someone whose movements required surveillance and scrutiny.

Rodríguez opens with one of the earliest photographic records of sex work in the Americas, Registro de mujeres publicas de la Ciudad de Mexico, de acuerdo con la Lefilacion de V.M.El Emperador (Registry of public women in accordance with the regulations issued by V.M. the Emperor). The Registro was created in the early 1860s as a public health project to prevent the spread of syphilis. According to Rodríguez, the Registro “instantiated a new biopolitical project of sexual surveillance, control, and regulation.” One new law required women working as prostitutes in Mexico to submit their pictures for inclusion in the Registro.

Each page of the Registro showcases four women’s pictures and biographies. The details of each person’s life were limited to name, age, address, place of origin, and profession, along with a record of the brothels that employed her. Although the Registro was designed to track and surveil prostitutes, Rodríguez is most interested in what the document can never reveal: the daily nuances of these women’s lives. In the two-page spread included in Puta Life, one of the women’s photos has been removed. “The blank lines below the initial image serve as the end of her visual imprisonment by the state,” Rodríguez writes. “I imagine a public health worker or curious state official finding the Registro and recognizing the face of his wife, sister, mother, grandmother, or perhaps treasured mistress pressed within these pages.” Here, Rodríguez imagines alongside the archive, allowing herself to wonder about all that is not contained in the official record, all that she cannot know.

Throughout Puta Life, Rodríguez stresses the limits of representation, performing the tension between knowing and unknowing. As she reminds us, opacity can be a way to “resist the move to know, comprehend, and capture the Other.” This gesture of imagining alongside the archive creates space for the viewer to acknowledge their gaze and desires. Rodríguez’s methodological engagement is inspired in part by two questions posed by scholar Saidiya Hartman about working with archives: “How does one revisit the scene of subjection without replicating the grammar of violence” and “How can narrative embody life in words and at the same time respect what we cannot know?” In her engagement with the Registro, Rodríguez performs a powerful gesture of care by modeling how we can do more than see these women’s faces and read about their lives, we can also sense them. Sensing requires us to attune ourselves to the archive’s fissures.

Photographers are obsessed with sex workers. Their images are everywhere in photography archives, found in every genre from studio portraiture to street photography. In a way, the history of sex work contains within it the history of the medium. Drawing a throughline between the nineteenth-century state registries of sex workers and the rise of street photography, Rodríguez highlights how the invention of photography helped create and maintain the visual figure of the puta in the public imagination at the same time it birthed a public that believed itself entitled to consuming images of puta life. Visual media like photography teach us how to identify sex workers, not as people, but as a type of human subject. Through her interventions in the archive, Rodríguez reveals how “the [new] technology of photographic capture was used as a system of surveillance intended to control racialized, class, and gendered access to the space of the public.”

Like the tabloid shots of celebrities I devoured in the early aughts, candid photos of sex workers are meant to capture something authentic about an experience or a place. “These supposedly candid images of women working the street position them as the natural inhabitants of cosmopolitan urban life, visually establishing the relationship between the sex worker and the street,” writes Rodríguez. Similar to the photos in the registry, these street shots create a visual impression of a type. They simultaneously produce and reinforce our ideas of what a sex worker looks like. The images also invite the public to look and assess.

Although street photography is believed to capture authenticity, candid images often reveal more about the photographer and the viewer than the subject fixed in the frame. Rodríguez reminds us that the image before us may reveal little about its subject. What we want to see is likely to be a reflection of our cultural training, context, and desires. When we consume glossy images of pop stars having mental breakdowns in 7-Eleven parking lots, we are enacting the cultural training from a dominator society that has taught us that we have a right to objectify and scrutinize women. When I pressured my mom to detail traumas from her youth, I was unwittingly acting out the misogynistic cultural belief that mothers exist solely to serve their children’s needs. I was also nursing a desire to know her that was rooted in curiosity and love. As I read Puta Life, I increasingly asked myself the same question: If representation does not necessarily reveal something authentic about the subject, what else might it reveal?

In the second part of the book, the puta speaks for herself. Rodríguez treats us to a deep reading of a classic puta memoir Vanessa del Rio: Fifty Years of Slightly Slutty Behavior. One of the most celebrated porn actresses of the 70s and 80s and the first breakthrough adult actor of color, del Rio forever changed the look and feel of adult entertainment. Her multimedia memoir blends pornographic imagery with horrifying and exciting life stories. Del Rio’s self-representation allows us not only to learn about her life but also to sense her. We get more than bald facts. We linger inside her unique worldview.

In one of the most trenchant passages in the book, Rodríguez dissects a disturbing scene of coercive sex in del Rio’s memoir. Del Rio describes having sex with a state trooper to get her boyfriend out of jail. As Rodríguez notes, del Rio’s cinematic narration of state-authorized rape is cinematic and foregrounds del Rio’s agency amidst violation. Del Rio tells us that she has an orgasm during her time with the cop, a fact she hides from him. She doesn’t want to give him the satisfaction. Here, del Rio’s orgasm is an act of revenge. She’s stealing pleasure. She’s taking back what belongs to her.

Where some might read del Rio’s framing as protective bravado or the eroticization of violence, Rodríguez sees agency. For her, del Rio offers a model for “transforming experiences of pain and violence and making them something else.” By authoring her own life story, del Rio offers readers an alternative puta cosmology where violence and abuse exist alongside joy and paradox. “Del Rio’s account of herself,” writes Rodríguez, “exposes the ways the experiences of racialized female subjects who are not white, middle class, or ‘respectable’ are made illegible within feminist frameworks that fail to account for the possibility of pleasure in the sexual lives of those who are constituted by violence.” This legibility is crucial because, as Rodríguez observes, “Latinas come to sexuality through multifarious forms of violence brought about through colonization, enslavement, migration, in the wounds of public and private patriarchy.”

Narratives of abuse and misery are ubiquitous in the puta archives. Less so are accounts of friendship, family, and daily life. In the closing chapters of Puta Life, Rodríguez explores our collective compulsion towards producing and consuming trauma narratives. Building upon her practice of imagining alongside the archive, Rodríguez asks us to consider what we miss when we focus on tragedy. How does our obsession with narratives of despair obscure moments of pleasure that also shape sex workers’ lives?

As I read Puta Life, I found myself unconsciously replicating some of Rodríguez’s imaginative work during phone conversations with my mom. I started wondering about everything I’d missed in my quest to expose the truth of our shared intergenerational trauma. Now when I listen to her stories, I imagine what other things she is revealing to me about herself. How can I use my unknowingness as a guide? Perhaps the greatest pleasure of reading Puta Life was watching its lessons manifest in my life in real time.

Throughout Puta Life, Rodríguez shows us what we can learn from engaging with the life narratives of sex workers. Their stories “offer working models for how others have navigated the circumstances that the inherited social order has provided.” For Rodríguez, the multimedia graphic text Sexile/Sexilio by Adela Vázquez and illustrator Jaime Cortez is a testament to the power of life writing. Like del Rio’s Fifty Years of Slightly Slutty Behavior, Sexile/Sexilio is an as-told-to autobiography, with Cortez serving as both illustrator and transcriber. Assigned male at birth in Cuba, Adela moved to the US and worked only briefly as a sex worker before becoming a sexual health educator in San Francisco. On her queer journey from adolescence to adulthood, Adela shares several moments of heartbreak, abuse, and trauma. “Like del Rio recounting her rape at the hands of the police,” writes Rodríguez, “Adela narrates these scenes not through the language of victimization and sexual abuse but through the lens of power and revenge.” Rodríguez encourages us to ask what we might learn from the puta’s rescripting of misogynistic violence. What can they teach us about surviving in a racist, misogynistic, transphobic world? As I read Puta Life before bed each night, I fell asleep wondering how I might likewise reinterpret my mother’s narrative silences, glosses, and good times within the framework of survival and desire.

Puta Life is a rigorous and nuanced contribution to affirming sex workers’ lives. This is reason alone to read it. But I cherish Puta Life because it offered me a new way of sensing my mother’s painful past and my own history of abuse beyond exposure. Above all, Puta Life gifted me with a deep respect for all I can never know about other women’s lives.

Elizabeth Hall is the author of the book I HAVE DEVOTED MY LIFE TO THE CLITORIS, a Lambda Literary Award finalist. You can find her on instagram at @badmoodbaby

This post may contain affiliate links.