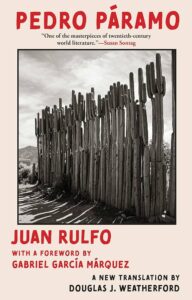

[Serpent’s Tail (UK) / Grove Press (US); 2023]

Tr. from the Spanish by Douglas J. Weatherford

To write about Pedro Páramo both critically and coherently is easier said than done. As Douglas J. Weatherford puts it in his translator’s note, “[The book] defies comprehension, with confusion and fragmentation becoming central to Rulfo’s unstable fictional world.” Juan Rulfo’s only novel defies logic. It is out to evade readers, to tease them for their attempts at understanding. Uncertainties, red herrings, and anxieties abound, all of which give Pedro Páramo its particular flavor. To remove these qualities, to replace the winding, erratic narrative in favor of clarity and chronology would be to transform the text beyond recognition.

While helping Carlos Velo with a film adaption of Pedro Páramo, Gabriel Garcia Marquez was presented with Velo’s attempt to chronologize the story. Velo had divided the temporal segments and organized them into sequential order. It struck Garcia Marquez as “flat and disjointed,” though seeing the story laid out thus only furthered his appreciation for Rulfo’s craft, his “secret carpentry.”

Looking through the book again, I return to the following quote from Garcia Marquez’s introduction: “I could recite the entire book front to back and vice versa without a single appreciable error, I could tell you on which page of my edition each scene could be found, and there wasn’t a single aspect of its characters’ personalities which I wasn’t deeply familiar with.” At first, this statement reeked of pretension to me. After my second reading, I checked the notes I had taken. Among the usual questions and pointers, the end papers were filled with nearly a page-by-page breakdown of the novel’s events and characters, both principal and secondary. So often does Pedro Páramo feel incomprehensible that what I had taken for pretension now seems like a prerequisite to understanding the text at all.

The book opens with Juan Preciado, our narrator, laying out his motivations:

I came to Comala because I was told my father lived here, a man named Pedro Páramo. That’s what my mother told me. And I promised her I’d come see him as soon as she died. I squeezed her hands as a sign I would. After all, she was near death, and I was of a mind to promise her anything. “Don’t fail to visit him,” she urged. “Some call him one thing, some another. I’m sure he’d love to meet you.” That’s why I couldn’t refuse her, and after agreeing so many times I just kept at it until I had to struggle to free my hands from hers, which were now without life.

Susan Sontag was right to declare that “we know we are in the hands of a master storyteller” from the beginning. It is a gripping opening that grabs the reader’s attention immediately. It is also deceptively simple. On subsequent readings, you can only look upon it as painfully ironic.

Following his mother’s emotional plea, Juan admits that he never expected to keep his promise; it would be hard to blame him, given how emotionally taxing the journey would be. However, recently Juan has found a “new world swirling around [his] head,” crowded with hopes and expectations for his father; as traumatic as the trip might be, he is urged on by the enigma of an unknown father and his mother’s dying wish. Juan sets out for the flaming town of Comala. “Many of those who die there and go to Hell come back to fetch their blankets.” Within the first few pages, a mule driver informs Juan that Pedro Páramo—“bitterness incarnate”—has been dead for years. Dolores’s dying wish will remain unfulfilled. The story we were expecting has already been ruled out. Now what?

Rulfo’s next move is to chronicle the life of Pedro Páramo himself, though these details are dished out sparingly. The eponymous Pedro is the son of Don Lucas, from whom he inherits the ranches that sustain the people of Comala. Although his father sees nothing but a barren future for his useless son, Pedro shows himself to be a fierce and destructive force, intent on ruling with an iron fist. To shirk his debts to the Preciado family, he decides to marry Dolores. The marriage doesn’t last long, ending when Pedro banishes Dolores over some trifling matter. This is a relatively tame entry in the book of Don Pedro’s atrocities, whose son, Don Miguel, is an equal scourge on Comala. Under their rule, it is a town of widows, unsanctified corpses, and illegitimate children. Even when faced with the depths of suffering himself, Don Pedro takes his frustrations out on the people of Comala. Following the death of his childhood love, Pedro crosses his arms and allows the town to rot.

Ostensibly, what is chronicled here is the false start of Juan Preciado and the story of Pedro Páramo. It is not only an attempt to paint a picture of the hopes and desires the latter has destroyed, but also an effort to reveal how he found himself in such depths of bitterness and disillusionment. It is not these events alone, however, that earn Pedro Páramo its stripes.

By the time Juan arrives, Comala is a far cry from what it was in Don Pedro’s day. After running into a few stragglers who knew his parents, Juan discovers that Comala is a literal ghost town; its streets are peopled with lost souls. Too poor to be absolved by the town’s priest before death, they are doomed to amble the streets, stuck between life and death: “This place is so full of spirits, a constant movement of restless souls who died without forgiveness and who have no chance of finding it.” Through the murmurings of these lost souls, we find out more about Don Pedro, as well as the countless others left roaming the town eternally. The extent of misery on display here is immense; these unearthly ramblings are full of regret and disappointment. As Susan Sontag puts it, “Being dead, they have nothing to express except their essence.” Juan is eventually so overwhelmed by these murmurings that they kill him. He wakes up in his grave, cradling Dorotea, an old woman from Don Pedro’s time, in his arms. He claims he must have suffocated to death, though Dorotea is quick to disregard this assertion. As a reader, the tumult of voices is often difficult to navigate. They drag us away from a traditional narrative and bombard us with their suffering. Having lived her whole life yearning for a son who never came, Dorotea seems to have finally satisfied her desire for motherhood. “For me Juan, Heaven is right here where I am now.” Curled up in the arms of her surrogate child, Dorotea is the only character throughout the novel who seems content.

The events that make up Pedro Páramo are ordered so as to be deliberately obscure. More often than not, characters die before they are introduced, and there are U-turns that dissuade attempts at chronologizing the story. Juan Preciado remains nameless for some forty pages, and the voices of the dead overlap so often that it requires close reading to prevent confusion. It is nearly impossible to know in which direction the story will move. During my second reading, I kept thinking about Carlos Velo cutting up the temporal fragments of Pedro Páramo. I imagined them all spread out on a table in no particular order. That image is how I remember the text; the events of this story are more like locations in space than points in time. Everything occurs, as Rulfo himself said, “in a simultaneous time which is a no-time.” It is a strange privilege to look down on a story through this eternalistic lens, one that few other authors can offer us.

The novel’s series of individual yet connected events is not random—this is not, after all, The Unfortunates by B.S Johnson. There is a secret logic to Pedro Páramo’s progression that a simple chronological tale wouldn’t afford. Hopelessness and unsatisfied desire run through the lives presented to us, and these themes are only heightened by the structure of events. We are usually introduced to a character’s ghost before their living days; we can only approach their past ambitions and hopes with guilt, knowing they will come to nothing. This story also has no real resolution. Ultimately, Pedro Páramo is killed by an illegitimate son, but we have known of his death from the opening pages. It offers no solace and only heightens the numbness that permeates the novel.

Beyond the confusion, Pedro Páramo focuses on the inevitable sadness life throws our way. The afflictions are suffocating, though so frequent and unavoidable that fatalism—not hope—feels like the only valid response. Consequently, Rulfo never lingers on a misfortune for long. Why would he when there are too many to count? As is made clear to Juan early on in the novel, “Hope? You pay dearly for that.”

Colm McKenna is a second-hand bookseller based in Paris, France. His reviews have appeared in The Latin American Review of Books and Dispatches Magazine.

This post may contain affiliate links.