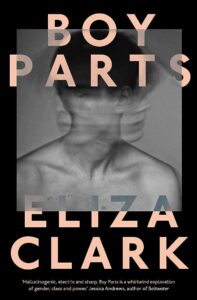

This spring, Eliza Clark was placed on the 2023 Granta Best of Young British Novelists list. The Granta list has become a barometer of the literary climate, signaling great titles coming from the listed authors. Clark’s second novel, Penance, was recently published, and she has a collection of short stories slated for a 2024 release (She’s Always Hungry). Her debut novel, Boy Parts, is now enjoying a second wave of fame with the adaptation at London’s Soho Theatre during fall 2023. This incendiary novel presents an innovative subversion of the male gaze in a dark comedy packaging, as well as poignant class commentary about northern England, through the eyes of an unreliable narrator.

Its gorgeous and talented narrator, Irina, takes fetish photography of average men she scouts—or, in her own words, “hunts”—on the streets of Newcastle. She styles male figures according to her preferences, profiting from the abuse of her subjects. Clark does not, however, stop at the metaphor of a toxic photographer’s female gaze. Boy Parts aims to be more than a straightforward observation on gender power dynamics.

By placing herself at risk during her photoshoots, Irina has us question how much it matters that she pushes the boundaries of consent and privacy. After all, one of her models attempted to rape her after a party. Irina becomes angry at the prospect of seeming vulnerable. Eddie from Tesco, a model with whom she grows to have a strange fascination, reminds her:

You want to think you’re not like other women, but you are, you know. You’re still . . . that’s still how the rest of the world, how men are going to see you. Like, I know you hate labels, but you like . . . You live in a woman’s body. You’re vulnerable. No matter what you think, you’re vulnerable . . .

Most of the time, however, Irina reminds us how vulnerable her subjects are. They are portrayed as naïve for trusting her. She asks the reader: “What about any of that read as safe, sane or consensual?” Still, she pushes the boundary further. Because Irina is an unreliable narrator, we cannot know how much she fights back against this presupposed vulnerability. We ascertain that she is hungry to be seen as a threat. “Do I have to smash a glass over the head of every single man I come into contact with, just so I leave a fucking mark?” She reveals to us what she is willing to do to achieve the perfect photograph, harming one of her models, whom she, in an eerie motherly manner, calls “my boy.” This revelation adds a chilling layer to Irina’s character, suggesting that she may get away with anything. It raises questions about the true extent of her agency and the boundaries she will cross in pursuit of her art. The reader is left wondering if her actions stem from a genuine desire for recognition or if they are driven by deeper psychological motives.

Indeed, Clark does give us a look into Irina’s past trauma. She does a wonderful job of making us sympathize with Irina at the start of the novel despite her arrogance. Going through her old photography, Irina also reviews her mental album of memories. Through little snippets in chapters, she shows us that hurt people do, in fact, hurt people. Asking herself where she acquired a taste for violence, she wonders how much agency she has had throughout various abusive encounters during her life. “Was it my idea to have him hurt me, or did he just let me think it was?”

Irina is so dangerously confident in herself that we cannot help but want more, though her actions raise ethical dilemmas and blur the line between reality and fantasy. Even when she hurts the men she photographs, they are mesmerized by her and persistently fail to ascribe any real gravity to her violence. Clark explores how consent can be manipulated or coerced. Irina has all her models sign a consent form before the photoshoots but continues to push and push until she is seen as a legitimate threat. She is frustrated that no one feels threatened. The question of whether she is really doing these things or if she is only imagining them turns her into an unreliable narrator who dissociates from reality. Irina is a great example of the “halo effect,” when people deemed beautiful by societal standards tend to give off positive impressions despite their behavior. She even confesses a horrific crime to a man in a restaurant, and he laughs it off as one of her quirks.

Irina is a toxic and abusive narcissist, but she—mostly—manages it with such coolness and a magnetism that is reflected in her interactions with others. Moreover, she provides such blunt and funny digs at men and razor-sharp commentary on class within England and on drug culture that the reader cannot help but fall for Irina’s one-liners and confidence. One of the characters asks her, and by extension the reader, to consider if all this female rage is pointed in the right direction. Where does the hate come from, and where should it go? “She asked me if I hated men, or if I liked men and hated that I liked them so much,” Irina tells us. The observations Clark’s male characters make about the world they live in can seem caricature-like, but in fact closely resemble statements many readers would have heard before: “I did a gender studies module in uni and im aware that men are trash.” Irina’s friendships also reflect troubling power dynamics. Her ex-lover and closest friend, Flo, is also mesmerized by her, writing obsessive Tumblr blogs about their relationship. Irina reads the “secret” blog and manipulates Flo to see just how far her love reaches. Furthermore, when her friend, Finch, asks for feedback on their photography, Irina does not hold back:

As you suspected, the heavy praise you received for these photographs was likely to be motivated by performative allyship. While technically competent, you rely heavily on your trans shtick and yeah top surgery is brutal, but I feel like it’s very obvious for you.

Clark also uses the novel to criticize the perception of northern women in southern England, complicating the perception of Irina’s cruel personality. Irina maintains that “Geordie girls [from Tyneside] are up there with Irish girls and Scottish girls; the black women of white women, you know?” The most poignant scenes are when Irina’s art overshadows a London nepo baby who is meant to share the same room with her during an exhibition, outlining how there is “still this entitled, still this generic, still this wealth of privilege and connections filling a void where there should be talent.” Later, Irina manages to get the boy’s uncle to buy all her photography and even joins him for dinner. He keeps asking her about what living in the north is like and why she would choose to stay there over London. He incessantly asks whether she prefers to be a big fish in a small pond and if they even have restaurants as classy as the one they are currently in “over there.” It is important to point out that Irina does have access to university education, even obtaining a master’s degree. Clark highlights how Irina is not the diverse voice in photography the man makes her out to be.

Clark’s ability to capture regionalisms—with all the connotations they carry—on the page is remarkable enough, but I particularly enjoyed the audiobook, which Clark narrates herself. Unlike many authors whose readings can be disappointing, Clark showcases her narrative skill in spoken word, as well. Most importantly, her own accent illustrates how she imagined Irina to speak.

As much as I have tried to do justice here to the novel and its wit, I must allude to a now-viral Goodreads review which brought me to the novel—“american psycho but for hot girls,” reads the five-star review by “cass.” While we could dismiss the commentary as funny but irrelevant, I do think it points to Boy Parts filling a need in the literary market for narratives about twisted women, both for unhinged female stories and a feminism which is not straightforward and neatly packaged in a “nice girl” wrapping. Instead, in the era of “I support women’s rights but mostly women’s wrongs” humor, Boy Parts serves us a delicious portion of transgressive female rage fiction, which goes beyond using violence for shock value.

Michaela Králová is a research assistant at Trinity College Dublin, focusing on queer identities, translation, and Ukrainian theatre. Originally from Prague, Czech Republic, she works as a translator, theatre-maker, and writer. Updates on her work can be found at @MaKrlov2 on Twitter.

This post may contain affiliate links.