[Mad Creek Books; 2023]

In my experience, literary translation is a labor of love. To successfully bring a novel, a poem, a short story, or a song (the list of possible media goes on) into another language, the translator really needs to know what the source text is about. Not just what each word means and how these words fit together according to rules of grammar and syntax, but also how each of these lines, paragraphs, and pages work together to pierce the heart of the reader. If the translator cannot sense the life pulsing within the source text, their work will remain the original’s moribund replica, no better, dare I say it, than an AI-generated translation.

Like any loving relationship, literary translation exacts both feeling and a hefty time investment. The translator will spend many a long hour with the source text, getting to know it and finding out exactly what brings it to life before the work of writing can begin. Their response, the translation, will be fine-tuned and polished, over and over again, until it comes that much closer to harmonizing with the original. Only love, it seems to me, can make it right.

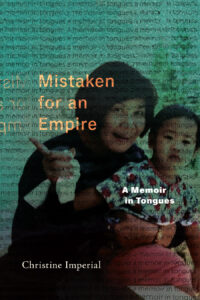

In Mistaken for an Empire: a Memoir in Tongues, the Filipino-American writer and scholar Christine Imperial questions her ability to translate a text she has every reason to hate: Rudyard Kipling’s poem “The White Man’s Burden.” A celebration of the American conquest of the Philippines, the poem became a by-word for the ideology of racialized imperialism upon its initial publication in 1899. In her memoir, Imperial asks how to bring the poem into Tagalog, one of the languages spoken by the people Kipling describes as “Half-devil and half child.” The riddle at the core of the memoir remains unsolved, the translation unfinished. Imperial admits that she skips passages in the poem that she doesn’t understand (such as Kipling’s reference to the Book of Exodus). Still, this conceit draws the reader into Imperial’s beautifully nebulous sense of self, her thoughts on belonging across languages, borders, and relationships.

Imperial does not translate “The White Man’s Burden” to “honor Kipling’s poem” or to make it available to a wider audience. Its audience is plenty wide: after all, Imperial herself had to study the poem in elementary school English class in Manila. Rather, she hopes that the task of translation will help her to improve her Tagalog, which is far weaker than her English. The limited scope of the author’s Tagalog is a recurring theme in the work and an obvious source of pain for its author. As a child, Imperial moved back and forth between the Philippines and California, and never quite managed to get a firm grasp of Tagalog, one of the two official languages of the Philippines (the other is English). Language problems give rise to feelings of in-betweenness. In her elementary school, Imperial was known as the girl who couldn’t speak Tagalog. In the United States, her Filipino accent is unmistakable. Even within her family circle, she is alternatively teased and praised for her American aura, her limited ability to speak Tagalog with anyone except the maids.

As this quip suggests, Imperial comes from a privileged milieu: She grew up with servants, her American passport allows her to travel and inhabit different countries with relative ease, and her linguistic dexterity has proven crucial to her emergence as a new talent in the English-language poetry scene. She discusses these advantages thoughtfully in the memoir, carefully drawing out and examining her unique set of privileges by contrasting her situation and outlook with those of others. Her grandmother, or lola, once lived in the United States and now finds it impossible to return, even for a short visit; she is always denied a visa, probably because she once had a Green Card and gave it up to return to the Philippines. We also encounter the incredulous voices of Filipinos and Americans alike who question Imperial’s position. By acknowledging the freedom she enjoys in so many domains of her life—this is, after all, what we’re really talking about with the word “privilege”—Imperial deepens, rather than muddles, our understanding of her placelessness. “Where do you call home?” the world seems to ask her. In over 238 pages, Imperial finds herself unable or unwilling to decide. But the question is there, itself a privilege. Because of her inherited gifts, Imperial is free to choose from inwardly and outwardly imposed markers of identity and to construct a literary domain of her own.

And freedom is the work’s prevailing stylistic principle. Billed as a memoir, the book is hardly recognizable as such. Imperial eschews a cohesive narrative about her experiences growing up as a dual citizen of the United States and the Philippines. Instead, she offers a constellation of poetry, prose, translation drafts in Tagalog, images, and ephemera that suggest her endlessly unsettled place in the world. Of all the work’s textual and visual forms, Imperial’s use of outside materials was most intriguing to me. By reference or direct quotation, she reflects on Filipino advertisements for skin whitening cream, American political cartoons from the turn of the nineteenth century, YouTube videos about Filipino table etiquette, trash TV shows like 90 Day Fiancé, contemporary news, clickbait articles on hospitality and happiness in the Philippines, text conversations with her lola, and insights from scholars of history, literature, and cultural studies. These snippets of other texts piqued my curiosity and led me to some very absorbing Google searches. They’re crucial to Imperial’s narrative thread, as well, revealing glimpses of her web of references. So many products of culture—high, low, public, intimate, past, and present—influence her self-composition, how she presents to others, and what Kipling’s words mean to her.

The choice to call the work a memoir, then, might reflect the author’s skepticism of the life writing genre. As she points out, personal narratives of belonging are in vogue, so much so that there “has been an influx of Filipino American poets writing about their identity.” But Imperial is afraid to give in to trends, so her book sets aside the tried and true formula. If the reader picks up Mistaken for an Empire expecting a familiar, multigenerational family saga about migration and inheritance, their assumptions will prove mistaken, and, in their error, they may wonder: When memoirs dwell on past injustices, do they instill us with a false sense of progress and moral superiority? What do people actually know about the lives of their ancestors and why should they (or anyone) care? Why must every critically-acclaimed family memoir include a quote from Barthes or Sontag? Although I am an avid reader of life writing, I still believe such questions are worth asking and am grateful to Imperial for prompting them.

I must admit that I found allusions to Imperial’s doomed relationship with her ex-girlfriend, Peyton, to be jarringly prosaic and, well, generic. Peyton, who makes the first of her brief appearances midway through the book, comes across as a no’goodun, if not a downright racist. She is described as white, “flat-nosed,” tall, and unfaithful. Her lines of dialogue reported in the book reveal her vanity, her self-serving ideals of racialized beauty, and her disinterest in literature; her only purpose in the work seems to be to undermine Imperial’s confidence as an artist and a human being. Whatever brought these two together is hushed up, a silence that need not be broken. At least, not until Imperial is able to view this romance as she sees her parents’ and grandparents’ (equally doomed) love stories: with compassion and distance.

Because of the text’s fluidity of genre and structure, it contains many other unsolved mysteries. Most obviously, Imperial never spells out exactly what is going on with her family and what led them to their present lives. Certain intrigues are suggested: how lola attained a Green Card; who her lolo, or grandfather, was; why her parents split up, why they moved to the United States, and why they returned to the Philippines. Each of these life events would provide fodder for a novel, a popular streaming series, another sort of life writing. And maybe they will, in the hands of a different author, one more interested in interpersonal drama or a universalizing social message than the poetic, hyper-individualized traces of non-belonging.

In a recent interview with Sarah Sophia Yanni about the memoir, Imperial notes that the process of translating Kipling’s poem came to serve as a leitmotif and an associative prompt, helping her to connect and generate the material. I have little doubt that Imperial could have written this work without such a keen focus on “The White Man’s Burden,” which, as we probably all agree, reads like a laundry list of imperialist values in the form of doggerel. Imperial herself admits to Yanni, “In Kipling’s poem, there’s no sense of love. It’s love for empire, but it’s very clinical and capitalistic.” I would say that Imperial is really translating something much murkier and more elusive: her perceptions, her guilt, her love for her family. And it is because of that love that her translation succeeds.

Jess Jensen Mitchell is a translator and PhD student at Harvard University, where she is writing her dissertation on contemporary Polish literature.

This post may contain affiliate links.