This essay was first made available last month, exclusively for our Patreon supporters. If you want to support Full Stop’s original literary criticism, please consider becoming a Patreon supporter.

When I first picked up The Stories of Breece D’J Pancake as a teenager, I was only aware that Pancake, like me, was from West Virginia, that he’d written these twelve stories when he was young, and that it was his only book. I didn’t know that Joyce Carol Oates had compared him to Hemingway. I didn’t know that his name showed up alongside Flannery O’Connor and James Dickey as a “Southern Gothic” writer, or alongside Tobias Wolff and Raymond Carver as a practitioner of “dirty realism.” As far as I knew, he was a local cult figure you had to encounter in the depths of the college library—a less prominent West Virginia writer than the historical novelist Denise Giardina, whom we read in school, or Homer Hickam, whose boyhood self was portrayed by Jake Gyllenhall in a Hollywood movie the same year I first read Pancake.

Pancake’s stories felt—and still feel—like private revelations. The inner lives of the truck drivers, boatmen, filling station employees, coal miners, and farmers who populate them feel so relatable, so human, yet at the same time bleak and inchoate. Their desires are often straightforward, but their ability to express or fulfill them remains beyond reach. Paragraph by paragraph, Pancake pries into the heart of his characters’ cruelty, regret, resentment, and tenderness with such unflinching determination that it’s startling. There’s something simultaneously confrontational and evasive about his writing. The characters feel stuck in place even as the narrative cuts freely back and forth in geological and historical time. Occasionally, the point of view shifts for a moment from the narrator into the coolly apprising eyes of a bobcat, a fox, a possum. In a way, the stories do something similar, observing with brutal impassivity the meanness and stunted hope of their characters.

The first and probably the best story of the collection, “Trilobites,” begins as its narrator, Colly, contemplates a hill that he’s contemplated many times before. He thinks about how it will always be there, “at least for as long as it matters.” As for himself, he’s not so sure. His father died while sinking a fencepost, the sorghum crop is full of blight, and his mother is trying to convince him to move with her to Akron, Ohio. Colly reflects, “I was born in this country and I have never very much wanted to leave.” The hill gets to simply exist in its place, but for Colly, whether he sticks around or ends up moving away, the prospect of leaving will always hang like a shadow over his pride of place. It hangs over the rest of the story too, along with the shadow of an airplane that Colly remembers from a time when he tried to run away; he “honest to god thought it was a pterodactyl,” and when he realized it was an airplane he was so mad he went home. His ex-girlfriend Ginny doesn’t understand—she’s moved away to Florida anyway. Nor does the reader understand at the surface level why the pterodactyl-airplane makes him angry, or why that anger spurs him to go back home. But for anyone who’s from a place that’s in some way difficult to be from, or hasn’t left home despite having every reason to, this passage, among so many others in the stories, resonates with the unbearable push and pull of home, the shadow of elsewhere, and the contradictory emotions it all stirs up. It’s a very West Virginia feeling to love your home but be unable to avoid thinking about leaving it. Or to have left and be unable to stop thinking about going back.

Breece Pancake himself left West Virginia after growing up in Milton, Cabell County, and graduating from Marshall University in Huntington in 1974. He spent the next—and last—five years of his life in Virginia. He first taught English at two military academies, then entered the MFA program at the University of Virginia under the tutelage of John Casey. He felt out of place among the Southern society kids at UVA and, rather than attempting to fit in, leaned into an unvarnished transmontane identity. As he wrote in a letter to his mother Helen, “Mother, I’m not going to go Ivy League.” He clomped around the halls of UVA in cowboy boots, took trips home in his Volkswagen Fastback, went hunting and fishing, bragged about getting in fights in bars, and showed off his gun collection. He also worked hard on his writing and made a reputation for himself as a precocious talent. His first publication, “Trilobites,” appeared in The Atlantic in 1977. A fine career as a writer looked set to open up for him. Privately, though, Pancake was a frustrated soul who wore his twenty-six years like an oppressive weight. On Palm Sunday 1979, after a strange incident in which he wandered—perhaps sleepwalked—into a neighbor’s house and scared her, he carried his shotgun out to a tree behind his rented cottage in Charlottesville and took his life. Helen later wrote in a letter to one of his advisors at UVA, “He saw too much dishonesty and evil in this world and he couldn’t cope.”

The twelve stories Pancake finished before he died were published as The Stories of Breece D’J Pancake in 1983. The book made an impression that was, if not massive, both indelible and sustained. He was by no means the regional secret I thought him to be when I first read him twenty-some years ago, and he’s become even less of one since. A 2004 biography (A Room Forever by Thomas E. Douglas) and articles in The New Yorker, Oxford American, The Believer, and The Mississippi Review, among others, considered and reconsidered Pancake’s legacy, paving the way for a new publication of the stories in 2020 under the title The Collected Breece D’J Pancake, which includes unfinished fragments of two novels and a selection of letters. In another letter to his mother he wrote, “I’m going to come back to West Virginia when this is over. There’s something ancient and deeply rooted in my soul. I like to think that I have left my ghost up one of those hollows, and I’ll never really be able to leave for good until I find it.” Perhaps the stories—stark as a gleam of moonlight, hard as an unseasonable frost—are his ghost.

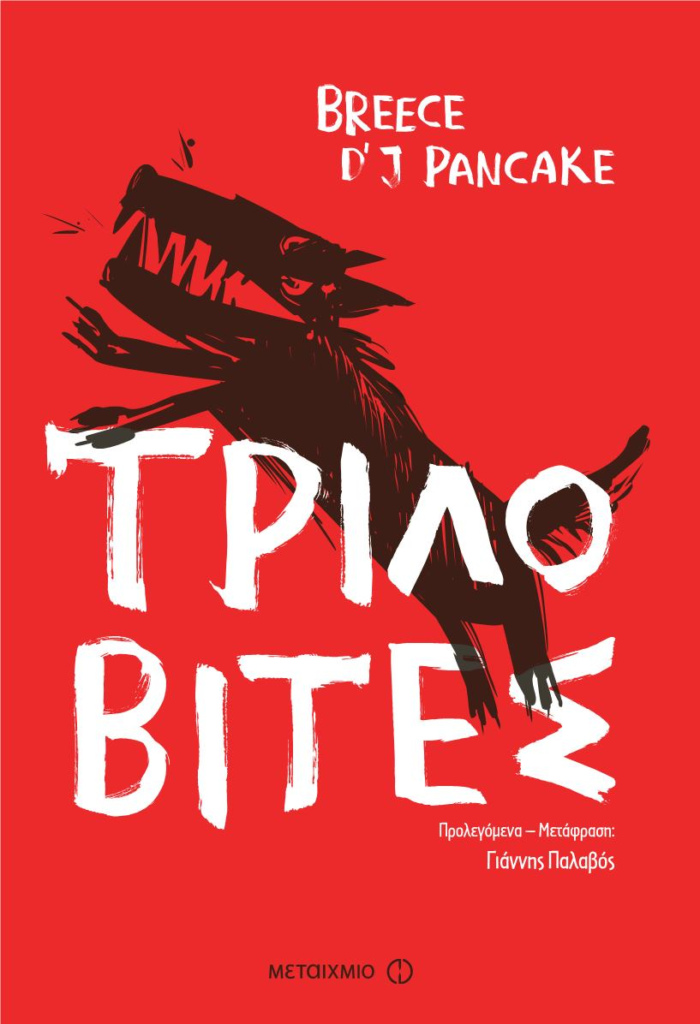

During the years that the literary world’s interest in Breece Pancake gathered pace, I left and returned to West Virginia over and over, always finding something to draw me away, despite, like Colly in “Trilobites,” never very much wanting to leave. I eventually ended up in Athens, Greece. One day, in a bookstore near the city center, I came across Pancake’s name on the red spine of a book. The title was Τριλοβίτες, Trilobites. I blinked. It seemed like some sort of rip in space-time, these stories that for me cleaved so tightly to my home far away, appearing here, in a different alphabet entirely. I flipped the book open to the first story, and there was Colly’s reflection that I’d first read in high school: “Γεννήθηκα σ’ αυτά τα χώματα και δεν μου πέρασε ποτέ απ’ το μυαλό να τα εγκαταλείψω.” I was born on this soil and it never crossed my mind to leave it. The translator was somebody named Giannis Palavos.

I was curious about how Palavos had rendered Pancake’s unruly language in Greek, so, armed with a dictionary and my mediocre knowledge of the language, I dove in. Phrases like “Don’t that beat all,” “Hell’s bells, I don’t know,” and “get all drunked up” pepper Pancake’s dialogue, along with eye-dialect spellings like “figger,” “eberbody,” and “when’d ya git yer…” In his translator’s introduction, Palavos says that rather than rendering the vernacular in some particular dialect of rural Greece, he preferred to use simple modern Greek. “Hell’s bells, I don’t know” is rendered “Τρέχα γύρευε, πού τα ξέρω” and “get all drunked up” is “γίνω ντίρλα.” Both are slangy phrases, but it’s slang that any Greek speaker from Thessaloniki to Heraklion would find familiar, and the spellings are standard. Most importantly, the idioms Palavos selected preserve the blunt informality of the original.

The next level of Pancake’s vernacular is more arcane and inventive. Who in this century has heard of “St. Vitus’ dance” (an autoimmune disorder that causes limbs to jerk) or “jake-leg” (Prohibition-era lower-limb paralysis from drinking contaminated Jamaica Ginger patent medicine)? Does anyone still know that “mackerel-snapper” is a derogatory term for a Catholic? Even “chippie” (prostitute) and “sinker” (doughnut) would elude nine out of ten readers today without ample context clues. The writing really gets going in phrases like “Chester got a case of rabbit” (meaning something like “shied away”), “anytime you get to feelin’ froggy, just hop on over to your uncle Skeevy” (trash talking, as in “any time, any place”), and “How many ya reckon’d walk out if I’s to dump the water Monday?” (a coal miner thinking about calling a strike).

With these phrases we get into the way Pancake is perceived as a regional writer. Most people who’ve written about him assume that he drew from a lexicon of uniquely West Virginian regionalisms, but I don’t think that gives him enough credit. Some of his colorful phrases can be traced to antiquated usages or youth argot of the 70s. Most of them, however, seem to appear in print for the first time in his stories, including “a case of rabbit,” “feelin’ froggy,” and “dump the water.” Their sound and feel, as he intended, reflect a working-class West Virginia demotic. He might have picked up some of these phrases from people he knew in Milton and Huntington, but my guess is many of them are Pancake’s own inventions, and that he was participating in the great country tradition of coining lively phraseologies.

Palavos’s translations of these more idiosyncratic phrases follow his rubric for the country vernacular: Stick with simple modern Greek. Thus the “dump the water” sentence becomes “Αμα τη Δευτέρα μπουκάρω στην τρύπα κι αρχίσω φασαρίες, πόσοι λες να πάρουν το μέρος μου;” which can be retranslated: “If on Monday I barge into the hole and start a fuss, how many do you say will take my side?” Perhaps there’s something lost in not pausing to wonder over an oblique phrase like “dump the water,” but on balance it seems like a good choice to err on the side of clarity. In the meta-analysis, a real head-scratcher of a phrase could make the reader of a translation wonder what the sentence was like in the original. As far as I could tell, plugging away at Τριλοβίτες, Palavos had done an impressive job of teasing through Pancake’s thicket of language and turning it into Greek that retained much of the same feel. Perhaps it was slightly softer than the original, but the sentences still had the stark, bitten-off feel that was so arresting.

I recently met up with Palavos for coffee at Kypseli Square in Athens. “Bald guy in the corner,” he texted me just before the appointed hour. He was tall and rangy, with an obliging manner and curious eyes. He’s a writer himself, and one of his own collections, Joke, won the Greek National Book Award for Short Stories in 2013. He’s translated William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, Jack London, Wallace Stegner, Ambrose Bierce, Donald Justice, Edgar Lee Masters, and Tobias Wolff, as well as various European poets. His prodigious literary enthusiasm was immediately apparent. As soon as we introduced ourselves, he recommended Argyris Chionis, a poet who’d grown up in the Athens neighborhood where I live, and began enthusing about Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio and “Greek Summer” by Jacque LaCarriere.

It was a roommate, Palavos told me, who’d discovered Pancake by way of an article in The Believer, and had hunted down a copy of The Stories to give him as a gift. He loved them and decided to translate them simply because he thought it was a shame no one else had. It certainly wasn’t for the money—830 euros for seven months of work. During those months he played Phil Ochs, Pancake’s favorite songwriter, on repeat. He trawled obscure internet forums to study how people talk about car parts and mining tools in Greek. He went through cycles of trial and error over and over.

Translating was Palavos’s way to keep in touch with language when he wasn’t pursuing his own writing. Crafting stories, or as he put it, “downloading them from your brain and heart,” he only did with difficulty. He hadn’t written anything of his own in a year and a half, since his collection The Child came out. He wasn’t sure what it would take to “go back to that place”—he referenced feeling more emotionally stable now, and so he didn’t feel like he needed to go to that place of downloading stories to the page. But he did need to be in touch with language. He viewed translation as a handcraft, meticulously solving a puzzle with repeated efforts. “You can learn so much. You should try it,” he encouraged me. I got the impression of a dogged technician, restless to keep tinkering. It reminded me of a quote from García Márquez’s translator Gregory Rabassa: “The translator, we should know, is a writer too. As a matter of fact he could be called the ideal writer because all he has to do is write; plot, theme, characters, and all the other essentials have already been provided, so he can just sit down and write his ass off.”

“I hope you didn’t find too many big mistakes,” he said. I hadn’t even found a small one, not that that’s why I’d read his translation. It had been a joy to witness, sentence-by-sentence, the care he’d taken in re-crafting stories that still felt, despite the increasing recognition of Pancake’s work, like secret West Virginian lore. I loved encountering favorite moments with a new Greek feel, such as when a character says to his prize bull, “Yessir, you look downright elegant,” which had become “Α, ρε μπαγάσα, για γαμπρός είσαι.” Roughly, “Ah, you rogue, you’re fit to be a bridegroom.” In a few places, Palavos’s translation even had the unexpected benefit of helping me understand a passage better. An example from “The Mark” was when one character says of another, “Boy, she was ripe the day he left.” I wasn’t certain whether it meant that she was sad or angry, and I realized that on previous readings I may have simply left that doubt unresolved. Palavos translated “ripe” with a Greek idiom that means “the herrings were crying for her,” or in other words: wretched, miserable, forlorn—not angry. I took another look at the original passage and saw that he was right.

Palavos told me a little about his background. He grew up in Velventos, a farming village in northern Greece. His mother worked as a seamstress and his father drove trucks and excavators for the coal mines in Ptolemaida. Palavos, like Pancake, is a peculiar surname—it means “crazy,” and that had made people laugh for as long as he could remember. He never felt like he fit in as a farmer and didn’t want to end up living his whole life in the village. His facility with language served as a way out, but once he found himself in artsy circles at university in Thessaloniki and later in Athens, he didn’t feel entirely at home in those circumstances either.

“I pretend to be this bookish person, but inside I know I’m hollow,” he told me. To explain what he meant, he referred to a friend who is a poet and opera singer. Her parents are a painter and a sound technician for the Athens Concert Hall. She was reading Dostoyevsky at fourteen, while at that age Palavos was watching Degrassi High and MacGyver, playing Nintendo and basketball, and collecting peaches in the orchard. Whereas his poet/singer friend fully belonged to the world of arts and culture, he felt not just like a latecomer, but an imposter. It made things even worse that, as time went on, the family money and class connections of his avowedly anti-bourgeois university friends revealed themselves. Palavos became increasingly aware of having a class inferiority complex. He’d been raised with a mentality that, in his words, blocked him from asking very much from life. Reflecting on this became motivation to dive ever deeper into literature, even though it still felt like a facade. When Joke won the National Book Award, he worried that the people lavishing praise on him would read it a second time and realize that it wasn’t actually any good. It took years for the feeling of being a cultural imposter to begin to recede. Perhaps it would never go away completely.

Breece Pancake’s hometown of Milton was, like Velventos, a small farming town situated a short drive from the coalfields. Pancake’s mother was a librarian and his father worked at a Union Carbide chemical factory. When he arrived at the University of Virginia, he found himself surrounded by upper-class Southerners. According to his advisor John Casey, being there was an experience in “status degradation.” “Breece didn’t know how good he was; he didn’t know how much he knew; he didn’t know that he was a swan instead of an ugly duckling. This difficulty subsided for Breece, but there was always some outsider bleakness to his daily life.” Another of his advisers, James Alan McPherson, characterized him as a “constitutional nonconformist” whose refusal to assimilate with the preppy in-crowd left him lonely.

The renaissance of interest in Pancake has inspired a lot of commentary about his lifestyle and class identity. People love to repeat stories that he kept squirrel meat in his fridge and ate roadkill, leaping to the conclusion that he “was reduced” to doing these things out of poverty. I think this assumption says more about received stereotypes than about Pancake. You don’t have to be poor for squirrel meat to seem like the makings of a good stew. As for fresh roadkill, if you’re up for skinning and cleaning it, then it’s an opportunity. Nevertheless, I have little doubt that Pancake himself was aware of how eating squirrel meat and roadkill would seem not only pitiable but also exotic to private school kids from Atlanta and Charlotte. I imagine that he took pleasure in scandalizing their preppy sensibilities by playing up what seemed rough and wild to them. The first time he met McPherson he asked him whether he drank beer, played pinball, owned guns, or hunted and fished. To others, he bragged about getting in fights at bars. Even if it’s true that Pancake didn’t know how good he was and how much he knew, whatever inferiority complex he had didn’t keep him from reacting to condescension with defiance.

The assumptions of the Pancake commentariat regarding his social class cut both ways. Several of the articles about him attempt a kind of gotcha journalism by pointing out a mismatch between the persona that he cultivated in Charlottesville and his background. The piece that Palavos’s roommate saw in The Believer, for example, emphasizes Pancake’s middle-class upbringing in contrast with the “lowdown and impoverished” characters he writes about. It declares, “Pancake disguised himself as part of the underclass so he could slip in among them and write about them.” It goes so far as to compare him to the disgraced New York Times reporter Jayson Blair, who filed stories “from” West Virginia without ever actually going there, concluding with the backhanded compliment, “The only difference is that Pancake got it right.”

This take gets it wrong in two ways. Firstly, Milton is a small town. Pancake’s neighbors, classmates, and the parents of his friends would have been people who resembled the characters he wrote about. They weren’t some sort of monolith apart, to be infiltrated for purposes of participant observation. As his distant cousin, the also-brilliant writer Ann Pancake, observes, “Growing up in Appalachia most often means growing up immersed in working-class culture, regardless of one’s own class position, and . . . merely stepping outside the region’s borders means an automatic class drop for most Appalachian natives.” No matter the fact that his parents had steady jobs and a solid, two-story house, class boundaries for young people are much more fluid anyway. In one of the stories, a character looks up at barn rafters where someone has daubed carpenter bee holes with axle grease to keep them from coming back—this is the kind of thing one knows from having been in barns. In Charlottesville, Pancake had enough money to rent a small house and buy gas for regular trips home. He didn’t have enough to attend the University of Iowa’s graduate program when they didn’t offer him funding. I don’t think that says much about whom or what he ought to know.

In any case, the generalization of Pancake’s characters as “impoverished” is an exaggeration. This is the second way the Believer article gets it wrong. It’s true that he wrote the stories at a time when the economic prospects of West Virginia’s small farms and coal mines were on the wane. An overarching sense of limited opportunities is rightfully present—a feeling of being blocked from asking very much from life. But if we read closely, we see that pretty much all the major characters in the stories either have steady jobs or are still teenagers, in some cases both. Colly’s mother wants to sell the farm not out of financial desperation, but because her husband has died and she wants to move closer to her family in Akron. Colly has fine options if he goes with her—college or a job at the Goodrich factory. Reva and Tyler, in “The Mark,” have a prize bull and board a tenant who helps them on the farm; Tyler’s brother owns a new Buick. The coal miners in “Hollow,” assuming it’s set around 1975, are making eight or ten bucks an hour, more than four times minimum wage—the equivalent of around $45/hour today. That’s good money. Ottie from “In the Dry” has a good job driving a truck, and the Gerlock family is outright well-off; their cars are “big eight-grand jobs.” There are a few destitute characters scattered through the stories, like the tramp chasing his newspapers in “A Room Forever.” But the only one that actually turns on financial hardship is “First Day of Winter,” in which Hollis’s family farm is failing and his brother Jake, a successful parson, refuses to take in their parents.

The grimness in Pancake’s stories and the fact that they’re set in Appalachia may connote, for some readers, the feel of poverty. That’s a serious misreading that denies their true reach. It’s not poverty that embitters the characters. The tragedies that strike them, the cruelty they show one another, and the regrets and self-sabotaging thoughts that torment them are features of human life that can surface anywhere, among any class of people. In Pancake’s voice, this bleak outlook on human nature manifests in a richly specific working-class West Virginian setting, but it has the ability to resonate anywhere. The narrator of “A Room Forever” pretty much sums it up when he reflects, “Nothing ever goes just the way it should.”

Palavos and I talked for long enough that we switched from coffee to beer (he quipped, of being Greek, “We have five thousand years riding on our shoulders and all we want to do is drink a beer”). At a certain point he looked at his phone and asked, “How do you say απορροφητήρας?” I knew what he was referring to, but couldn’t for the life of me think of the most common term for it. Vent hood? Range hood? Kitchen extractor fan? Stove vent? Nothing sounded normal. Maybe there were regional variations, like soda/pop/cola? A real-time translation puzzle. I thought of the hours he must spend second-guessing decisions on little matters like this. In any case, he said, he was very sorry for the interruption but he had to call his girlfriend because apparently their απορροφητήρας had caught on fire. “Let’s hope she’s alive.” After a short call, he reported, “She’s alive, at least. She’s cooking pastitsio, so…” and shrugged in a way that conveyed, even if everything was going to shit, there was at least going to be something good to eat.

“Let’s hope she’s alive” was a joke, but in it was a hint of sensitivity to the possibility of tragedy. I sensed the same thing when he talked about why he’d never gotten a driver’s license. Even as a teenager, when all his peers were starting to drive, he imagined how awful it would be to cause an accident and hurt or kill someone. Pancake’s story “In the Dry” vividly describes the long-term emotional aftermath of a car wreck that paralyzed one of the characters, and I imagined it having special resonance for Palavos. Only now, at the age of forty, had he hesitantly started to take driving lessons.

This trait of sensitivity to the possibility of tragedy reminded me of a feeling I get while reading Pancake’s stories: a compulsion, almost a duty, to contemplate terrible things. Teenage prostitution, callous violence against animals, vicious grudges between people who need each other’s support the most. These elements aren’t there just to be “gritty” in an aesthetic way. The stories challenge the reader to admit they know about the cruelty and despair that exist in the world, to bear witness to them, and to acknowledge that our reasons for continuing on nonetheless will always be imperfect. Pancake can’t look away, and he uses the power of his hard words to compel his reader not to either.

Part of the raw germ of his perspective can be found, perhaps, in a long, outraged letter he wrote to his mother after a trip to Mexico where he saw fathers selling their daughters into prostitution. Helen told a reporter, “He came back and said there was just no point to living. . . . He said, ‘You all reared me too well.’ Maybe he meant we should have told him such things existed in the world.” That outrage, that mortification, metamorphosed through his writing into a kind of bitter but clear-eyed mourning. The characters and language in Pancake’s stories are relentlessly unsentimental, but lurking within every story is a soft heart grieving for the world. Even, almost imperceptibly, flickering with hope, like at the end of “In the Dry” when Ottie leaves the despair and false piety of the Gerlock family behind. As he walks back to his truck, he “knows that what turned them all will spin them forever.” Implied is the idea that he doesn’t have to be mired in their dead-end cycle. The gears “—ten through forward—strain to whine into another night.” They make “an awful noise,” but at least they have the promise of moving him away from the suffocating past.

The admiration that Pancake’s twelve stories have continued to attract is well-deserved, but what people think they know about him sometimes threatens to suffocate his legacy. The fixation on whether he was too hillbilly or too middle-class, the sticky idea that his stories revolve around poverty, the perception of his characters as stand-ins for the “dregs” of society—these errant framings pop up with dismaying regularity in articles about him, sometimes coming off as some sort of West Virginia–stereotype free association rather than literary criticism. Even the usual comparisons to the “dirty realist” authors like Carver and Wolff, as complimentary as they are, can feel limiting, as if the only praiseworthy element of Pancake’s stories is their aesthetic feel. Likewise, lumping Pancake in with the Southern Gothic writers is an ill-fitting box simply because West Virginia isn’t the South and so doesn’t share the historical valences underpinning that genre.

My conversation with Palavos, however, showed me that not all comparisons needed to feel limiting or incorrect. He told me that he thought Pancake wrote in the tradition of Ivo Andric, Bruno Schulz, and Amos Oz—writers rooted in particular rural or small-town settings, who created stories with universal appeal. This felt right. Pancake’s stories are as inextricably identified with their setting in the small valley towns and folded hills of southern West Virginia as Schulz’s are with Eastern European Jewish neighborhoods or Oz’s with the kibbutz. I particularly loved the comparison with Andric, the Nobel Prize–winning author of The Bridge on the Drina, for whom leaving and returning home was a lifelong occupation. Born in Bosnia to Catholic Croat parents, he had a long diplomatic and political career, but throughout the time he spent in Zagreb, Belgrade, Vienna, Berlin, and numerous other European cities, he insisted on maintaining contact with the small Bosnian towns where he’d grown up. They were the well of his creative work; he never wrote about anywhere else. As his fame grew, so too did jealousy between the different claimants on his identity amid a shifting political landscape—Croat, Serb, Catholic, Bosnian—but in his books all the characters have the fullness and foibles of real people, irrespective of the community they’re from. It felt like a real compliment to compare Pancake to a writer of such alert fidelity to human experience and such faith that his hinterland home was the right place to look for it.

Palavos summed up his admiration of Pancake this way:

He transformed his suffering and his weakness and his inferiority complex into painfully real stories of what it means to be alive—part helplessness, part hope, part beauty, part effort to create meaning despite the fact that death will claim everything. You guys are lucky over there in West Virginia to have a writer like Pancake.

These words, and my entire conversation with Palavos, led me to let down guards I didn’t know I had up. Not for a moment did I feel the intrusion of an irrelevant stereotype or stifling comparison. Perhaps, without realizing it, a part of me had begun to wish Pancake’s fame had never grown beyond the depths of the library where I found him, to wish his brutal brilliance was a secret known only within the state borders. But to encounter someone whose admiration of his stories was both deeply perceptive and unencumbered by any of the cultural baggage I’d grown tired of . . . that was freeing.

Eventually, inevitably, we slid into talk of homesickness. Palavos talked about missing the north of Greece—the woods, the lower prices, larger portions in the tavernas, rain, snow, and fog. “Where I grew up is the only region in the country that has no geographical or cultural connection to the sea,” he said, “and that shows in the people’s mentality.” Stranger to blue water, I thought. Years before, I had passed not too far from his village on a road trip. I remembered rounded mountains socked in by heavy gray clouds. Rockier than the ridges of West Virginia, but similar enough to tickle something deeply rooted in my soul.

It was felicitous that Palavos’s background seemed to position him so well to connect with the ghost of Pancake through his stories and translate not just the puzzle of their words but their underlying spirit. Not because the two men were particularly alike—Pancake was reportedly brash and loud in public, Palavos soft-spoken and self-deprecating—but because they both felt driven to leave their backwater towns only to grapple elsewhere with feeling inferior or like an impostor, and often be thinking about home. At root, that’s what lends the best of Pancake’s stories their unique charge: the specter of leaving. I could sense it just as strongly in the Greek translation and eventually I had the thought that, despite being on their face a difficult prospect to translate well—so colloquial, so rooted in a particular place—this quality of concern with leaving home predisposed them to exist beautifully in another language. A regional literature, finding itself far away, reaching back toward home.

Gabriel Rogers is a woodworker and essayist from West Virginia. He studied nonfiction writing in West Virginia Wesleyan’s MFA program. His essays have appeared in Still, The Waking, Kestrel, and Hairstreak Butterfly Review. He lives in Athens, Greece.

This post may contain affiliate links.