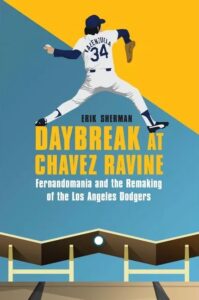

[University of Nebraska Press; 2023]

At a time when Esquire magazine is publishing 2,500-word lamentations on the disappearance of sports books, Erik Sherman’s Daybreak at Chavez Ravine is a rare and worthy project. Rare, Jordan Teicher argues in Esquire, because reporters tasked with conjuring endless hot takes and instant analyses have neither the time nor the resources for sprawling stories that become books. With venues like Sports Illustrated and The Sporting News reducing their frequency or shuttering print runs entirely, there’s little hope of reviving the once proud tradition that gave us Moneyball, Wait Till Next Year, and Ball Four—classics still being read decades after their publication.

The American baseball historian Erik Sherman wants to swim against this tide. Sherman started out writing for Community Life Newspaper in Westwood, New Jersey as a teenager in the 1980s. He later became a stringer for the Bergen Record and authored his first sports book in 1995. Sherman’s newest work—Daybreak at Chavez Ravine: Fernandomania and the Remaking of the Los Angeles Dodgers—follows the career of the great Mexican pitcher Fernando Valenzuela, particularly his near instant rise to stardom as a rookie in 1981. According to Sherman, Valenzuela almost single-handedly “helped to unite a racially divided city simmering with anti-Mexican sentiment,” and “forever changed the Dodger Stadium landscape, creating multiple generations of Mexican American fans.” It’s the kind of layered premise perfectly suited to the sports book form.

Daybreak gets off to a rocky start when Sherman reveals that Valenzuela, who has never cooperated on a book or movie about his life, doesn’t grant Sherman any interviews. Undeterred, the author cites Gay Talese’s seminal New Journalism essay “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold” (also originally published in Esquire) as inspiration to persevere. Talese, sent to interview Sinatra, was famously rebuffed by the Chairman’s people and had to craft an essay without speaking directly to ’Ol Blue Eyes. The result is one of the finest magazine articles of the twentieth century.

Sherman hopes to offer a similarly evocative portrayal by interviewing “those in and around” Fernando’s inner circle. Success is then declared, as Sherman claims in the preface that his book captures “a truth about the man that wasn’t known by even his biggest fans.” Except that the depiction of Valenzuela in Daybreak at Chavez Ravine is exactly what you’d get talking to his biggest fans: He’s a down-to-earth guy, an incredible pitcher, and an inspiration to millions of Mexicans both in this country and back home. Heartwarming, yes, but not a portrayal that has anyone clamoring for more.

To fill twenty chapters requires endless repetition. Valenzuela is described as an “icon” or “iconic” twelve times; “humble” on eight occasions; “quiet,” sixteen; “shy,” another sixteen. I enjoy repetition, up to a point. This goes way past that point. Sherman diligently recounts the press conferences, magazine covers, White House appearances, and attendance spikes to illustrate the sheer magnitude of Fernandomania. I get it, it was big. As for the man behind it all, we learn that Valenzeula liked to tap people on the shoulder, only to disappear once they turned to look. Hilarious stuff. I’m not sure what’s sadder—Fernando’s version of pranking, or the suggestion that this detail suggests a secret, mischievous side of the man.

Valenzuela did usher in massive changes to the Dodger Stadium landscape, and the about-face of Latinx fans toward their local team offers the most potential intrigue in this book. Three short, early chapters are devoted to the history of the Latinx community’s clashes with Los Angeles institutions, including the forced eviction of more than 1,800 Mexican American families from Chavez Ravine (so named for Julian Chavez, the area’s first landowner back in the 1840s) largely by eminent domain seizure. Residents were told the area would be used for a public housing project—Elysian Park Heights—to which they would someday be able to return. It never happened. By way of explanation, Sherman writes only that the “initiative would eventually be canceled amid the Red Scare hysteria brought on by McCarthyism.”

The elided history goes something like this. In 1953, the newly elected Los Angeles mayor Norris Poulson opposed public housing as “un-American.” With the backing of a group called Citizens Against Socialist Housing (CASH), he set out to undo the city’s contract to build Elysian Park Heights. Proponents of the project met with immense hostility. Frank Wilkinson, the assistant director of the Los Angeles City Housing Authority and one of the main supporters behind Elysian Park Heights, faced questioning by the House Un-American Activities Committee. He was then fired and sentenced to a year in jail for contempt of congress. Still, the 1958 referendum to trade 352 acres of Chavez Ravine to the Dodgers and their owner Walter O’Malley only passed by three percent of the vote. Dodger Stadium opened for business in April 1962.

How did one pitcher reverse all these ill feelings to win over LA’s Latino population? Could Fernandomania have been even bigger without such a sordid past to overcome? Did the younger generation simply view the Battle of Chavez Ravine as ancient history?

Sherman leaves these questions unanswered. If Mexican American baseball fans had any ambivalence about flocking to this place, we don’t hear much about it. Instead, Sherman seems to assume that Fernandomania was powerful enough to wipe away the past entirely—an especially odd assumption, considering Sherman does tell us that the Mexican American labor leader Cesar Chavez “refused to ever set foot” in Dodger Stadium. Strange, then, that Sherman refers to Valenzuela in the opening pages as a “reflection” of Chavez. The two men may have both been heroes to the Mexican people, but it’s a disservice to lump them together based on that fact alone.

If we’re not diving further into Latino perspectives on this history, then what’s left to write about? Not much, it turns out. Daybreak at Chavez Ravine quickly devolves into a collection of meandering stories, many of which are only tangentially related to Fernandomania, LA, or even baseball. Some barely qualify as stories: like when Dodger manager Tommy Lasorda got into a car, put a song on the radio, fell asleep, and was recognized by another driver. That’s it. That’s the anecdote. “He’s got his head back, and people were driving next to us and going, Oh my God! That’s Tommy Lasorda! You could read their lips. It was like, Oh my goodness!”

Sports figures are known for talking in clichés, and saying nothing while doing it, but the beauty of writing a book is you get to leave things out! Do we really need one of Fernando’s teammates saying, “I would hate to attempt to put into words what he meant to Mexico”? This quote might create sympathy for an author trying and failing to accomplish that very task, but it serves little other purpose.

I can’t help thinking Sherman could’ve done more with the resources at his disposal. Take, for example, this excerpt from Ben McGrath’s 2007 New Yorker profile of the mercurial Red Sox superstar Manny Ramirez:

When I asked his teammate David Ortiz, himself a borderline folk hero, how he would describe Ramirez, he replied, ‘As a crazy motherfucker.’ Then he pointed at my notebook and said, “You can write it down just like that: ‘David Ortiz says Manny is a crazy motherfucker.'”

You won’t find any descriptors like these in Daybreak.

The author Michael Lewis says it “irritates” him “immensely” that he hasn’t found another sports story worthy of deeper exploration like Moneyball or The Blind Side. He writes in the afterword to the former, “As always happens when the material is strong, the story became telescoped in the writing. I felt compelled to jettison everything that didn’t have to do with putting together a baseball team.” In Daybreak, the opposite happens. No story emerges from the material, so Sherman is compelled to include every quote from every bit player. We’re left with a collection of fireside tales, interesting only to the people telling them.

If you go searching for a story and come up empty, do you still write the book? I don’t know. But I have the nagging sense that if Sherman had interviewed a lot more fans and fewer ex-players, coaches, and managers, there may well have been a story to find.

Matt Matros lives in Brooklyn, NY with his wife and son. His work has previously appeared in Electric Literature, Chicago Review of Books, Heavy Feather Review, Necessary Fiction, the Washington Post, the Ploughshares blog, and The Westchester Review, among other places.

This post may contain affiliate links.