[Tender Buttons Press; 2023]

Telaraña—Spanish for spider’s web—comes from the Latin root tela meaning web, warp, or loom. Lucía Hinojosa Gaxiola’s debut collection, The Telaraña Circuit, operates through webbed logics; one articulated thread causes another thread in the expansive network to tremble with multiplied resonance. Gaxiola expertly weaves sound, image, and word in a rigorous investigation of history, memory, and language.

The text is hybrid, multimedia, and multimodal, encompassing Spanish and English, handwriting and typewriting, language and image, leaves and stones. The section “Cavity as Emanation” serves as a poetic statement that reveals Gaxiola’s framework and methodology. She writes, “This book is dedicated to women archeologists, to the meticulous, sensuous act of unearthing as a curious listening, where methods of excavation transform into a haptic process involving affection, care, re-cognition.” She goes on to describe the archeological research conducted by her aunt, Margarita Gaxiola González, which became, for Gaxiola, “a map of intimacy” and “a generative symbol of fragmented memory.”

Gaxiola is a connoisseur of the fragment. She unearths, brushes off, arranges, and presents pieces of language like slivers of pottery sifted from the ground. She writes, “I’ve gathered here residual traces of performances, ephemeral actions, notes, experiments, and poems from the last few years.” In this way, she becomes an archeologist of her own creative process, which she overlays onto her aunt’s research by experimenting with poetry as form of fieldwork that might tap into the decaying matter of familial memory. At the end of the opening poetic statement, Gaxiola writes, “While paying attention to the practice of memory and its inscriptions . . . the notion of borders, bodies, and limitations develop into a process of frictioning.” Though friction might cause irritation, it can also produce generative energy, the heat of a struck match.

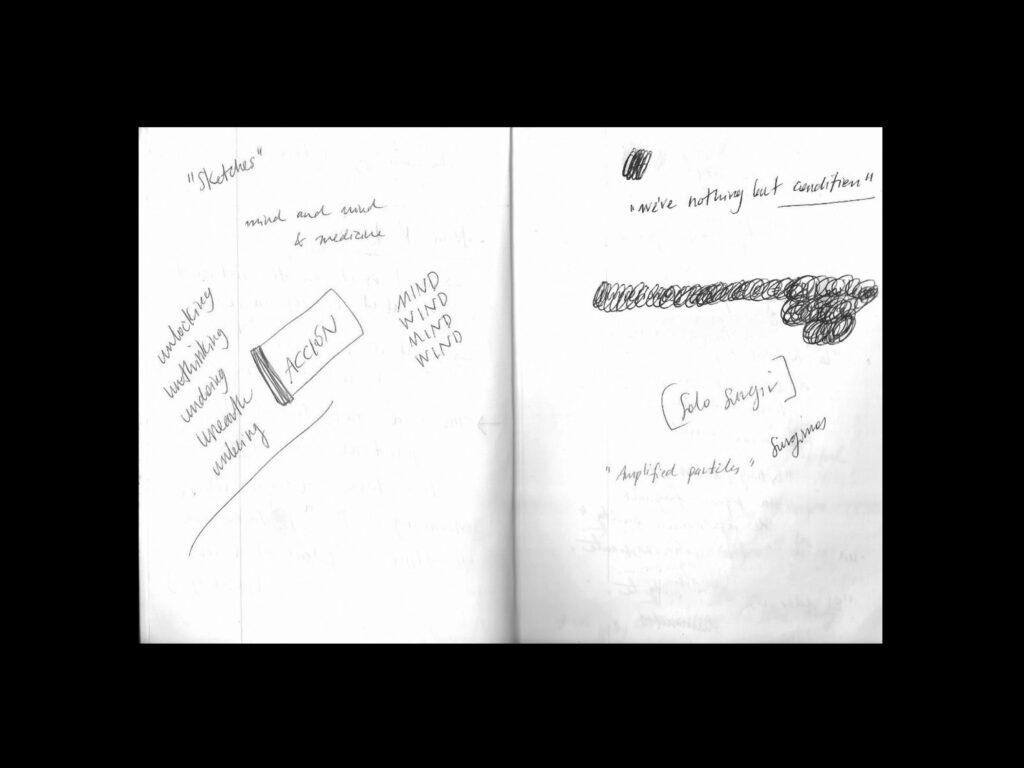

It is fitting that the poems in the collection are inflected by scans of handwritten notebook pages. One early page lists atmospheric sounds (“waves of the sea,” “distant cars”); the next muses on punctuation in language as musical notation. Gaxiola is priming the reader to apprehend the text as a score that ultimately requires sonic activation from page to air. The presence of handwriting establishes textual intimacy; the idiosyncratic motion of a writer’s hand on the page conveys the particular rhythms and kinetics of their thought process. The hand is the funnel through which thoughts pour into the container of the notebook via the ancient psycho-technologies of mark-making. As Gaxiola asks: “Is language a limb, a vibration?”

In shape, the titular poem’s stanzas mimic the diagrammatic images of pottery shards that are interspersed with the text: wide on top and tapering into points. The language, without capitalization or punctuation, runs together, “waiting for your perception” to extract meaning. Buried within this poem is a definition: “the telaraña circuit is a radio impulse connect or broadcast while doing / something else a traveler with a broken bag gathering fragments in / transit i thought you were coming but i am always late trying to unpack / the chorus the second stanza the last wordimage trying to translate the / mechanism into micro-prophecy.” In other words, when one tunes into the frequencies of this “telaraña circuit,” one polishes one’s antennae, seeking to distill symbols from the living text of the world.

A major challenge of archeology is the tension between excavation and preservation. Unearthing and handling fragments can lead to their further erosion. Similarly, with poetic language, sometimes the act of analysis and interpretation can lead to the erosion of meaning; the initial thrill of significance may crumble beneath the sustained pressure of explanation. However, The Telaraña Circuit demonstrates new practices of reading or listening that avoid the pitfalls of overt sense-making.

In the next section, “Toponym,” fragments are scored with slashes to separate words and phrases. At points, the letters stretch apart to test the limits of words: “d e s c e n d e r / p a r a / a s c e n d e r” (descend to ascend) echoes down the page. Archaeology and poetry are both practices of communing with an underworld. Gaxiola writes, “es un video para las sombras / para los insectos / para las moléculas de dios / para los futuros en potencia // para nadie” (it’s a video for the shadows / for the insects / for the molecules of god / for potential futures // for no one). What does it mean to create art not only for humanity but for the immaterial dimensions of our world?

In “Infinity Scrolling,” Gaxiola further physicalizes language by incorporating a typewriter, a mechanical tool that exists between the modes of handwritten and computer processed text. Metabolized through this machine, language shatters, scatters, and stutters. Unfastened from the rigid line imposed by word processing software, words and letters become sinuous and sinewy, taking on more organic formations. On one page, “dissolve” explodes from within, turning into a flurry of s’s that follow an oblique downward path toward “solve” in the lower right-hand corner. This material approach to language loosens the bonds of the constituent parts and allows underlying meaning to surface.

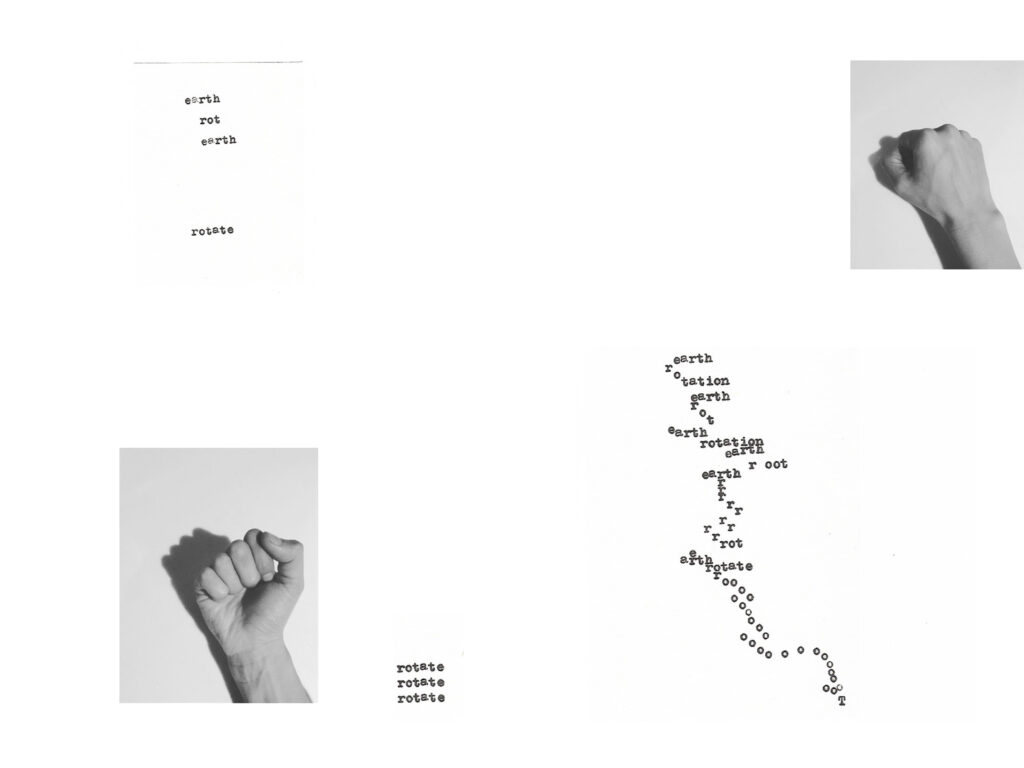

The title of this section plays on the infinitely regenerating and backfilling “feed” of social media, which is designed to be navigated via fingertip. This concept is accentuated by black and white photographs of a hand and its shadow in various states of flex: fingers outstretched and curved; a gently closed fist. Gaxiola draws attention to how language is an extension of the body and the world. She notes that “words are / raw / like / meat they / smell and / can also / ROT” and “this / paper is a / field but / everything is a field.” The field—a landscape continually unfolding beyond the horizon—is the real-world infinity scroll.

The metamorphosis of language continues and intensifies in “Decompositions.” A single sentence, “we become as we erode,” recurs across five pages. The words expand and contract, finally atomizing into a mist of individual letters, another example of language literalizing meaning on the page. This creates an impression like a murmuration of starlings or a cloud of gnats, something living and multitudinous.

The poem “Mantra” adheres to an earlier exhortation to “keep mining / the hidden / elements of things” by probing the intersection between language and body:

accepting

the doctrine

that the

microcosm

of the

human body

contains all

the particles

of the

macrocosm

/ this poem

reveals the

minerals of

vowels / or

the vowels

of minerals

/ containing

the number

of elemental

particles in

the human

body /

What follows is a list, in Spanish, of each element present within the human body and its corresponding percentage of body composition by mass (such as “oxígeno 65%”). On the facing page is a list of the vowels in the name of each element (such as “oíeo”). As the former list counts down to increasingly minute quantities, the latter list condenses scientific language into the pure non-denotative sound of open-mouthed incantation: “óoo,” “auiio,” “aioio.”

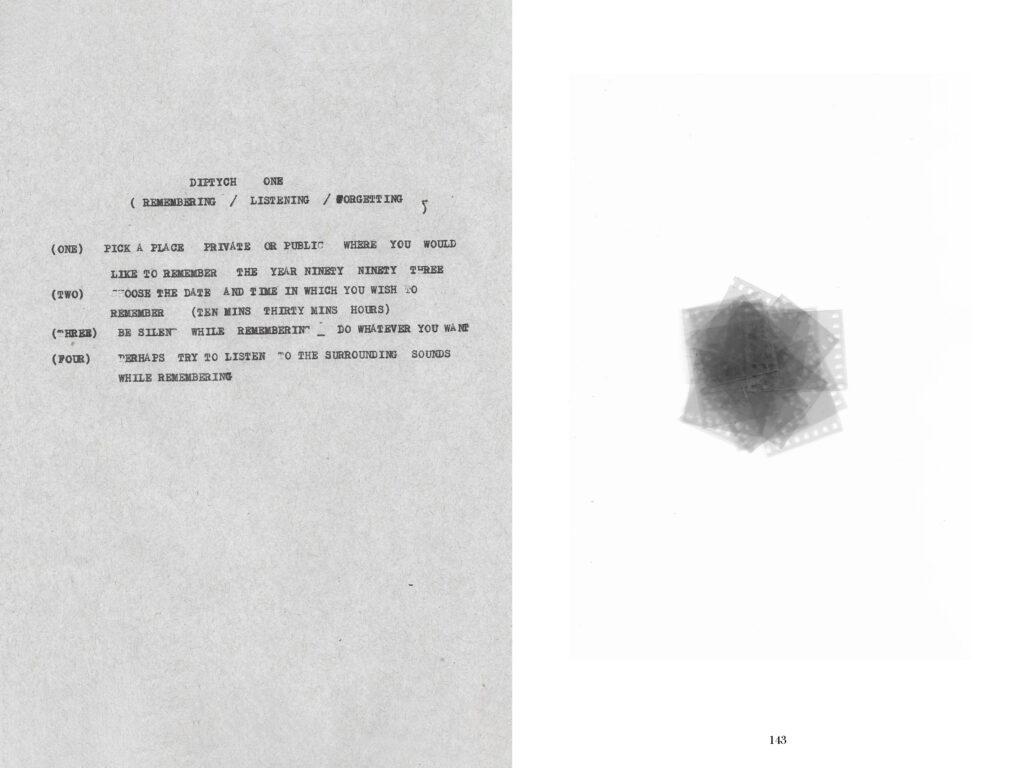

The closing section of The Telaraña Circuit, “Olvidar 1993,” presents some notes and film negatives from a series of rituals that Gaxiola performed with family photographs. She poured water over the negatives and then gave this water to the plants in her studio until she “was surrounded with disembodied images that were alive.” Through this procedure, Gaxiola resurrected captured memories and integrated them into a natural cycle of life and death in hopes that “an archive might record its own decay.” She later invited family members to “silently remember the images that had disappeared while [she] recorded the sounds surrounding their silence.” A few of the negatives are scanned so that the images are visible, giving the reader a glimpse into a specific past. Many more of the negatives appear on the page as imageless shadows. Into these perforated, opaque frames, each reader might project their own eroded memories, the silences and gaps that too deserve regard.

In the endnotes, the reader can see how the fragments, traces, and residues collected in this book have already existed in the world as performances, installations, and collaborations. As Gaxiola stated in a discussion on “Publishing-in-Transit” hosted by The Brooklyn Rail, “All the process that happens is also the poem.” The form of the book is capacious enough to hold the many unfurling tendrils of process. And under the sign of process, preoccupations of legibility and illegibility fall away in favor of “the question that must remain open like a / note that never / ends.” To read The Telaraña Circuit is to accept an invitation to listen deeply to the vibration of “the tectonic shifts of language.” Gaxiola’s “poetics of friction” highlights the edges of things—words, bodies, memories, countries—and the points of contact which may be smoothed or remain jagged.

Clare Lilliston is a writer and editor based in Seattle, WA. Clare received an MFA in creative writing from Mills College, where they were a Community Engagement Fellow, and a BA in literary arts from The Evergreen State College. Clare’s reviews of small press poetry books have appeared in BOMB Magazine, Cleveland Review of Books, and Full Stop, and their poems are published or forthcoming in exquisites; Bombay Gin; Action, Spectacle; The Tiny; sPARKLE & bLINK; Mary: A Journal of New Writing; and The Encyclopedia Project.

This post may contain affiliate links.