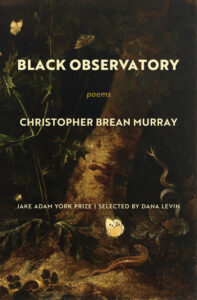

[Milkweed Editions; 2023]

Christopher Brean Murray’s poetry collection Black Observatory draws readers into situations and landscapes both familiar and disorienting. Readers attend a poetry reading, find the point where a path becomes visible, spend time near the seashore and at professional conferences, even venture into an abandoned cabin in the wilderness. A mixture of flash fiction-like prose poems and sensory-laden verse, the collection itself is the black observatory. Certainly, a mysterious place—a black observatory—exists within the collection. It is a disjointed place where scientists behave like ghosts, but the idea of a black observatory also captures the nature of Murray’s commentary in these poems. At points it feels like Black Observatory borrows the connotation of “black” used in “black humor,” engaging humor as a way to deal with the absurdity lurking within many basic and not-so-basic aspects of life.

Many of the poems have a gothic feel, with abandoned camps that resemble horror movie sets, mysterious structures in out of the way places, and a variety of hauntings. The eponymous poem appears near the end of the collection, with the title having been repeated in two other poems—“The Haunted Coppice” and “Salvaged Travelogue.” Examining that “black observatory” is a revealing way to analyze the collection.

The “Haunted Coppice” begins with a familiar image of a fading trailhead, drawing the reader into the space where nature and a manmade environment merge:

At the end of the dead-end lane

clogged with burr-shagged tangles

and pricker-studded stems, within earshot

of the trickling rivulet that probes the margins

of the warehouse district, one encounters

the inauguration of a path.

Heading down this path, we learn the speaker “strolled that track many times in my youth.” Readers likely explored similar paths. As the poem continues, the clear imagery gives way to questions, accurately capturing how artifacts of imagination outlive observations of reality in our memories. The speaker accurately recalls inventing “frightening myths” with friends:

One tale followed

the exploits of a deceased soldier who wandered

the forest in search of his misplaced sidearm.

But when trying to reconstruct the landscape from memory, details fade:

Didn’t that trail

lead to the black observatory that hummed

like a power station beside a secret landing strip?

didn’t an estuary appear through the foliage,

it’s cobalt waters cleaved by a white yacht’s hull?

In “Haunted Coppice,” the black observatory is a dimly remembered location shrouded in mystery. The observatory is similarly described in “Salvaged Travelogue,” where the lines run together without grammar and the imagery feels even more disjointed than in “Haunted Coppice”:

The trail led to the swimming pool in the woods

It continued to the black observatory

The rain was over there we were getting wet

The dog barked an hour slid a thermos just can’t vanish

The ranger in the distance appeared to be praying.

Like “Haunted Coppice,” “Salvaged Travelogue” features indistinct places accessed through rain, unexplained events (a thermos just can’t vanish), and a tension between reality and imagination that continues the gothic presence punctuating the collection.

The poem “Black Observatory” follows “Salvaged Travelogue.” This prose poem hews closely to flash fiction and composes an eerie account of the speaker’s visit to the location foreshadowed in previous poems. It begins:

A man disappeared around the side of the observatory. I followed

but he was gone. I found only a propane tank and a rusted gardening

tool. Through the fence and hedgerow, I glimpsed a copper-colored

sedan parked across the street. Its engine started, and it sped away.

This scene feels like a fraction of a spy novel or an episode of “Stranger Things,” with heavy, unknowable things happening in curious environments. This poem makes it clear that the black observatory is, in fact, an astronomical observatory, but it is ill kept and the subject of its observations remains unknown:

The birds built a nest in the telescope, but the

astronomer set out poison. He wasn’t in the pool when I arrived.

A white ball bobbed on it surface like a moon. Was he sending

messages with lasers to the inhabitants of other planets? Was he

scanning the heavens with the telescope, hoping a comet would shoot

through his retina into the star-smeared void of his mind?

Describing the astronomer’s mind as a void is a contradiction; shouldn’t a scientist engaged in research have a mind full of thoughts and theories? If he is sending messages to aliens, wouldn’t those messages fill his mind and wouldn’t he be sharing the contents of those thoughts with the extraterrestrials? Everything in this poem, as in many others in the collection, feels hypothetical, theories about theories.

Not all of Murray’s poems adhere to such dark atmosphere and hypothetical uncertainty. Other poems toy with uncertainty in more familiar or playful ways, such as the first poem, “The Welsh Scythe.” The poet asserts that a Welsch Scythe “is better than a Swiss lathe or a Scotch spade.” The poem continues to list and compare tools, each paired with a national identity. Often, the speaker comments on their quality without respect to their functions or any particular trait:

Spanish forceps: I acknowledge their originality and verve.

They could easily seduce a naïve journeyman.

I, however, remain unconvinced

by the Italian whipsaw, the Hungarian bench plane,

the Danish spike, and the Russian boilermaker’s hammer.

What does the speaker find unconvincing about these tools? It is unexplained, but the language reminds the reader of conversations in which the history or context of the object is implied. For example, Japanese cars are dependable while German cars are money pits. American-made chainsaws are better than those produced in China. In each of these statements, as in the poem, the quality is implied and appended to the national identity. The history is embedded in the object and needs no elaboration. By making up imaginary objects and comparing them on non-essential attributes, the poet questions if our biases against who produces tools or origin really carry as much meaning as we assume. The list forms a humorous critique that feels so close to real language that it’s difficult to notice the nonsensical nature of the assertions. This critique, wry and lightly cynical, may be called a form of black observatory.

In several poems throughout the collection, the poet lists objects to characterize people. Some of these people seem to be personal acquaintances or fictional characters, like Knut in the poem “Knut,” the disappearing roommate who left one box “filled with photos of someone else’s life” and another “full of soccer uniforms.” The speaker knows little about Knut and learns little more from the objects left behind (“were you a coach?”). Divining another’s life through forgotten objects yields another dark observation.

At least one person in the collection, the poet M.S. Merwin, joins us from the real world. His poem is named “M.S. Merwin.” Murray’s gentle humor resonates with anyone who has attended poetry readings:

He talked for over half an hour before reading a poem.

Time is illusory, he said.

It passes, but it also stands still.

Some poets speak through their poetry, while others prefer to add a bit more context. An audience member may appreciate context and sidebars as a glimpse into the person writing the words while another listener may thoroughly desire for the poet to get on with the poetry. And, summarizing Merwin, Murray does get on with the poetry, ending on two beautiful observations from its namesake:

Animals have language, he said.

And we have imagination.

Some of Murray’s poems are more playful and forgiving than others. For example, “The New American Painters” questions Merwin’s assertion that “we have imagination.” The painters,

stroll through town in pigment-straked shirtsleeves. They’ve allowed

their hair to grow long. Without exception

they wear beards.

In short, they look like painters. The speaker observes that,

Though they once conspired in private to overturn

the dominant paradigm, they now declare

their intentions in cafes.

Of course, they are starving artists who sometimes leave the cafes without paying. Their workspaces are as predictable as their grooming and finances. They paint on,

monumental

canvases crammed in draughty studios

across whose bare wooden floors

empty wine bottles roll.

The painters are perpetuating stereotypes; there is little new about them. Change from one generation to the next relies on self-knowledge and historical awareness so that one can identify how to change, the meaning behind evolution, and which paradigms need revision. These painters are not up to those challenges. One painter flings paint with eyes closed. Another vents their frustration on the canvas,

stepping on it, spitting insults,

only to resurrect it and continue

the feverish brush strokes.

What is produced by this method? “It resembles the bald head of a screaming Incan / glimpsed from above.” Like previous American painters, their work is colonial and appropriative; the Incan painting in the poem is called “The Codex,” a title that would more appropriately describe a painting of Aztecs. How do the painters explain their work? They don’t. Instead, “they just gesture toward it, as if it’s meaning is obvious.” In a way, the meaning is obvious. The painters lack self-awareness, which results in little intergenerational change and ultimately a dearth of meaning in their art.

It’s important to acknowledge that Black Observatory likewise addresses ecological themes with the same dark, sometimes cynical tone, but also with the same humor. In “The Invisible Forest,” a speaker moves through an urban landscape permeated by images of nature.

I would’ve sworn it was a thriving

metropolis, yet pine-scented winds

rushed between buildings. I saw

a fawn lapping a puddle of rainwater

outside my apartment, but I was late,

so I hurried on, my moist hand

gripping the handle of my briefcase.

To the reader, it is unclear if civilization has overwritten nature or if nature is reclaiming the urban environment. Some of the imagery is pedestrian while other images are dystopian, calling into question the clear warning one might expect before societal collapse.

A monitor showed a burning car

weaving through a crowd. I

pushed through the turnstile,

descended to the platform,

and poured with the others

into the over-crowded train car.

Does normalcy persist in a world where New York City is choked by wildfire smoke from burning Quebec forests? How much does daily life change when someone guns down dozens of children in a school hundreds of miles away? What are we noticing about the changes going on around us? The final image of the poem feels like at once a warning and, perhaps, a thread of ecological hope:

As the doors slide shut, I heard the coyote cry.

Black Observatory has been a difficult collection to capture in a review largely because Murray’s poems say so much in accessible-yet-unique ways. It covers a wide range of experiences and observations with a slightly sardonic tone that will likely feel relatable to many readers. The book also includes themes of urbanism vs. pastoralism, predicts directions of social change, and draws history from collected objects. It is a museum and an observatory in one. The collection was selected by Dana Levin for the Jake Adam Yorke prize, and it is not hard to understand why Levin would want to honor Murray’s work. This collection contains revelations, warnings, reflections, and, of course, observations that make the reader feel a little less alone in uncertainty and less afraid while still being afraid.

Eric Aldrich‘s recent work has appeared in Full Stop, Terrain.org, Essay Daily, and Deep Wild. He lives in Tucson, Arizona.

This post may contain affiliate links.