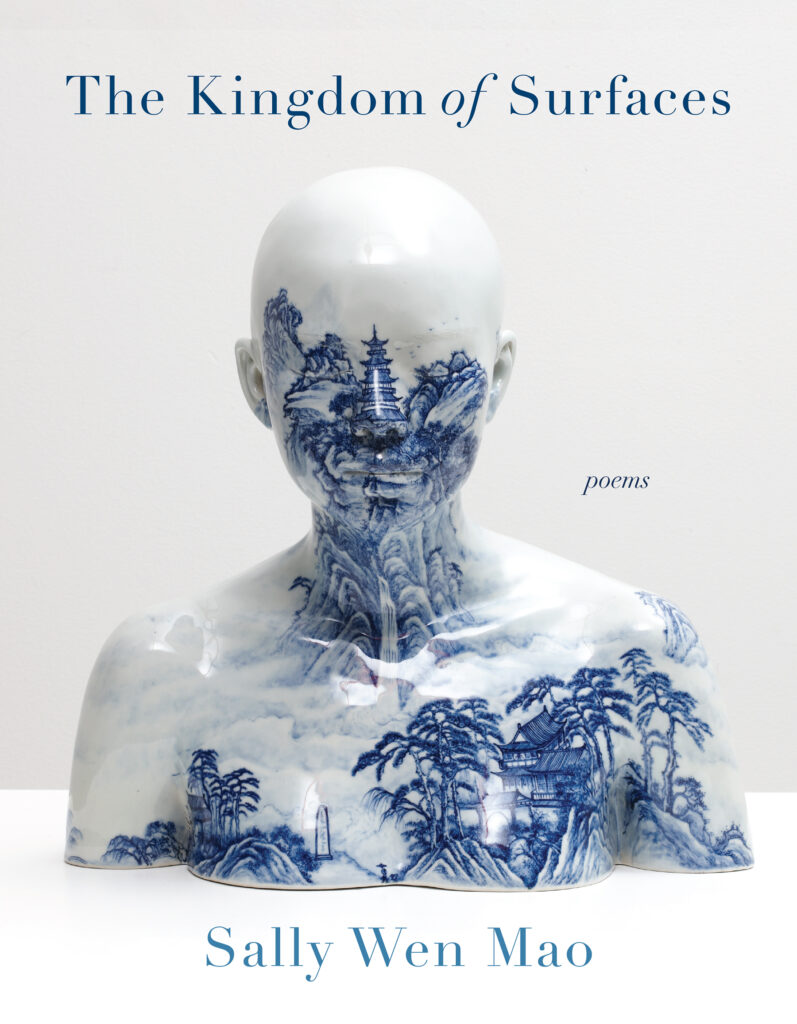

[Graywolf Press; 2023]

As a Black person, I’m aware that so much of my culture, such as music, clothing, and food, has been—and continues to be—co-opted by white Western capitalists. However, I am also aware of how it hurts to hold space for two implications from this: (1) those same white capitalists won’t do anything to stop my community’s suffering; (2) how nice it is to receive acknowledgment of how our art holds the majority of society together. Sally Wen Mao’s The Kingdom of Surfaces is an honest portrayal of the evils of commodification as well as what we humans are willing to suffer through or cause suffering upon for the sake of beauty.

In the title poem, there are different sections headed by chapters in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass, and each section’s epigraphs are quotes from a book about a 2015 exhibit at the Met: China Through the Looking-Glass: Fashion, Film, Art. In the final line of the first section, “Looking Glass House,” Mao writes through the lens of the speaker’s gaze: “Do these surfaces awe me? Yes. My own yes disturbs me.”

Mao’s poetry collection centers on the history of products from the Asian continent, such as porcelain and silk, while examining the violence inflicted on the very people responsible for their creation. While there are great uses of form such as haibuns, contrapuntals, sonnets, aubades, and prose poems, the centerpieces of Mao’s collection are the “On Porcelain” poems that introduce each section of the book. These are differently shaped in the forms of porcelain vases. Each successfully dichotomizes the past and present of the Asian diaspora’s suffering. One section of a vase attests to the history of violence committed by British colonizers to the Chinese for their glassware, silk, and other artifacts:

If the Royal British Army sacks a

City / Breaks the glass / Ransacks

Treasures / Rapes the women

and transports the art / To

the Buckingham Palace,

Is that what they mean

by civilization?

Another section of a vase comments on more recent violence:

One year into the pandemic / In Atlanta,

a white man shoots / Kills eight people

Most were Asian women / He regards

Not as “people” but “temptations” / As a

policeman parrots his words to the press

The final poem of the entire collection is entitled “On Garbage.” But it is not in the shape of any vase to display how all these vases, and the people and things like them, although treated as disposable, deserve the utmost respect. It demonstrates this by compiling couplets and tercets, which celebrate what is broken (like Kintsugi porcelain mentioned in the preceding poem):

because it gave me hope

to rescue what was abandoned,

what was beyond repair.

Mao demonstrates the timeless disposability of Asian women by showing how often they are the recipient of harm as well as the bearer of labor for other people’s visual and physical consumption. Therefore, it makes sense that she uses words that sound like their ongoing pain and labor:

Inside the kiln of history, a porcelain chest drum burns, beats, breaks. We tread

on frail and frayed and afraid as we are, to a kingdom with a better imagination.

Silkworms always die for human imagination. It’s a miracle that I am wild. Silk

moths know only captivity and survival is the exception.

There is a plethora of poems that use such words with “or” and “ur” sounds to reflect the sound of “silkworm.” Mao explains that silkworms must be used up to the point of killing them for successful silk merchandise to be sold, “If the silkworm survives and becomes a silk moth, the silk is ruined.” She makes sure we and the speaker are haunted by the silkworms’ ache in phrases such as, “How is it that two fistfuls of these husks/are worth [italics my own] more than my life,” “To burn is to burnish a dead kingdom/with fine lighting [italics my own],” and “But ‘inspiration’/is the wrong word for a forced opening [italics my own].”

As the speaker of The Kingdom of Surfaces continues to float in and out of the ethereal China: Through the Looking Glass, she is told that to become queen, she has to feel fire. So she has a dagger that “turns into a scepter in disguise”; she is ready for her “suicide mission.” This an example of the occasional parallels between the speaker and the striking film character Tu Tuan, and the actress who plays her, Anna May Wong:

In Limehouse Blues, Anna May plays a resplendent woman, Tu Tuan, who dances

for a club, the Lily Gardens, owned by her lover, a Eurasian man in yellowface. He

falls for a homeless pickpocket, a white girl named Toni, housing her and ignoring

all of Tu Tuan’s warnings. Later in the film, Tu Tuan takes a dagger and impales

herself with it.

Both the speaker and Tu Tuan seek a sense of empowerment but are forced to hurt themselves to achieve it. Another example of parallels between the speaker and Anna May Wong is in “Minted,” where the speaker compares her own commodification with actresses’ as the first Chinese American woman on a coin:

How we’ve grown used to being used once, expend-

able. You, me, pretty commodities: fungible,

fungal, funny, fun. Fun! But for whom? No glory

to girlhood or Hollywood . . .

Your father was a laundry man. Every day of his life,

he encountered stains. A century later, I drag

my linens to the laundromat, trade dollars for coins

with your face on them.

Throughout all the heartbreak and death, my favorite part of the whole collection is the prodigious repetition of the word “alive.” It supports the speaker in reclaiming the ongoing narrative about her community, whether that narrative is written by systems, non-Asian people, or even herself. For example, “I will never dance for you,” Mao writes, “This dance / Taunts you with my aliveness.” The reader has to sit with many instances of Asian women, including the speaker, receiving racist and patriarchal harm. But in this instance, the speaker is tired (hence the anaphora “I quit” in the beginning of the poem and the line, “I’ve got nothing for you / So fuck you”), but she is alive. Her aliveness represents one of the collection’s many acts of resistance amidst centuries of breaking glass.

Mao takes more than her own community with her in this book. In “On Silk,” she displays how whiteness is not the only form of bigotry capable of harm; she recounts Langston Hughes receiving anti-Black hate on his trip to Shanghai. In the “On Porcelain” poems, she includes Black liberation along with Chinese American liberation, particularly by reflecting on the tragedies of both Black people and Asian people lost early in the pandemic.

One year into the pandemic / In Atlanta,

a white man shoots / Kills eight people

Most were Asian women / He regards

not as ‘people’ but ‘temptations’ /

. . .

We march / For Black liberation / For Indigenous land and water

America / We march / An uprising / To vitrify is to transform

We become the chimera forged in fire / Sum of a long summer

As an African American poet, I have often read work by Asian American poets who critique people for culturally appropriating their culture, but often believe they get a pass for appropriating Black culture in a way that made me uncomfortable. It is refreshing to see Sally Wen Mao fiercely depict the fetishization of Asian culture while holding the complexities of appropriation.

Maya Williams (ey/they/she) is a religious Black multiracial nonbinary suicide survivor who is currently the seventh poet laureate of Portland, Maine. Ey published essays in venues such as The Daily Beast, Black Girl Nerds, Honey Literary, and The Rumpus. Their debut poetry collection Judas & Suicide is out now via Game Over Books. Their second poetry collection Refused a Second Date will be out October 2023 via Harbor Editions. Follow more of her work at mayawilliamspoet.com

This post may contain affiliate links.