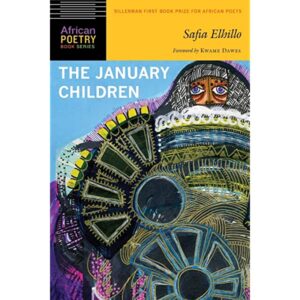

[University of Nebraska Press; 2017]

Safia Elhillo’s debut poetry collection, The January Children, is a masterpiece that beautifully blends nostalgic yearning with piercing commentary. Through her delicate language, Elhillo explores her intricate connection to her native language, homeland, and the history that has shaped Sudan’s destiny. The collection revolves around the concept of the “January Children” of Sudan, referring to those born under British occupation who were all assigned a birthdate of January 1. These individuals symbolize the transitional generation caught between the traumas of colonialism and the postcolonial struggle for identity and belonging.

What sets The January Children apart is Elhillo’s skillful use of revolutionary song lyrics, historical documentation, and intimate self-portraits that link Sudan’s troubled history with family memories and the complexities of language. The collection immerses readers in a captivating exploration of love, loss, and the collective experiences of individuals whose lives have been profoundly influenced by Sudan’s history. Elhillo seamlessly weaves in the imagery of fruits, natural oils, and spices, creating a stark contrast with the underlying themes of grief, exile, and loss.

Throughout the collection, Elhillo draws inspiration from the lyrical presence of Abdel Halim Hafez, one of Egypt’s greatest musicians, evoking the question of why she is drawn to him. While a supplemental essay explores Elhillo’s connection to her native language, homeland, and Sudan’s history, it does not explicitly mention the reasons behind her fascination with Hafez. To shed light on this aspect, consider linguistic and cultural links between Sudan and Egypt during the period under discussion.

The Arabic language serves as a potential link between Elhillo, a Sudanese poet, and Abdel Halim Hafez. Given that Arabic is widely spoken in both Sudan and Egypt, it is plausible that the shared linguistic heritage between the two countries played a role in Elhillo’s connection to Hafez’s music. The nuances and beauty of Arabic poetry and lyricism may have resonated with Elhillo, leading her to find inspiration in Hafez’s work. Furthermore, Sudan and Egypt shared a close cultural connection during the period encompassed in The January Children. While the supplemental essay does not explicitly delve into the historical ties between the two countries, at its core, it highlights Sudan’s struggle for identity and belonging in the postcolonial era. A nuanced comprehension of the historical backdrop uncovers that Sudan, akin to Egypt, endured a period characterized by colonial rule. Hafez’s secular love songs, praising the beauty of “the brown girl’s eyelashes,” hold a unique historical position, emerging after a period of oppressive colonial control and preceding a Sudan where laws restrict women’s freedom of expression and bodily autonomy. These lyrics personify a brief period of freedom in Sudan, when Marvin Gaye can be heard on the streets, and “all the alcohol in khartoum” has not yet been “poured into the nile.” Hafez’s secular love songs may have symbolized a moment of liberation and freedom for Elhillo. This temporal and cultural connection could have contributed to her admiration for Hafez as a representative of a freer, more idealized Sudan. By utilizing this framework, Elhillo’s yearning and romantic longing for Hafez, as evident in the collection’s various titles that directly reference him, such as “date night with abdelhalim hafez,” can be interpreted as her yearning for a liberated and idealized Sudan. Elhillo implies Hafez’s influence without explicitly naming him in the body of the poems. Instead, the focus predominantly lies on the abstract exploration of the interplay between their identities. For instance, in “date night with abdelhalim hafez,” the opening lines unveil a tender love story between Elhillo’s parents, which not only serves as an intimate glimpse into her family history, but also carries profound symbolic weight:

the story goes my father would never unwrap a piece of gum

without saving half for my mother

the story goes my mother saved all the halves in a jar

that’s not the point.

This anecdote recalls the fractured nature of Sudan’s history while subtly foreshadowing her parents’ impending separation. Her mother’s saving all the halves in a jar suggests a longing to hold onto the fragments as if preserving the memory of what once was. This hints at an underlying sense of loss and a recognition that unity and wholeness are slipping away. The fractured nature of Sudan’s history finds resonance in the personal narrative of Elhillo’s parents, in which their relationship becomes a microcosm of the larger societal fractures.

As she goes on, she speaks to him directly, still without name:

i can’t go home with you home is a place in time

(that’s not how you get me to dance)

i’m not from here i’m not from anywhere

The lines “i can’t go home with you/home is a place in time” convey a profound sense of displacement and temporality. In expressing that she does not feel a sense of rootedness in a physical place, she suggests that her concept of home transcends the confines of a specific location. The phrase “home is a place in time” hints at the idea that her understanding of home is connected to a particular moment, an intangible and ever-shifting experience that defies a fixed geographical reference. Elhillo’s deliberate choice to address Hafez directly without explicitly naming him invites a subtle interplay of shared experiences. By forging a connection through the likelihood of a shared sense of separateness and isolation, Elhillo forms an empathetic bond with Hafez that transcends national and cultural boundaries. In this exploration of identity and displacement, Elhillo presents an intimate dialogue that delves into the intricacies of personal longing and the universal quest for a stable sense of self.

By incorporating found text and diverse documentary materials, Elhillo provides invaluable cultural context, enriching the reader’s understanding of the interior landscape she creates. One notable example is the poem “the part i keep forgetting,” where she skillfully layers significant documents, interviews, and articles to explore the essence of Sudan’s existence and the impact of arbitrary borders. Through this assemblage of perspectives, Elhillo breathes life into the common experiences of individuals, offering a fuller and more nuanced portrayal of her subject matter. In the “Notes” section that follows the collection’s main body of poetry, Elhillo cites an array of culturally significant materials, including soundbites from an interview series with her mother and other members of the Sudanese diaspora and selections from the textbook Sudan Today (1971). A great demonstration of Elhillo’s documentary innovations can be found in the poem “the part i keep forgetting.” The verses are divided into two distinctive stanzas, with the first section opening:

sudan is cracking around the edges is a

singed bit of paper is cracked by a river in

two is new border fresh wound soldiers

standing in the street [sudan was always an

invented country] sudan in grainy

photographs & dalia’s been arrested &

yousif’s been arrested sudan broke my

mother’s heart [i came from a sudan that had gardens & magnolia

flowers] [now i’m not

from anywhere] cut open my uncle’s back

[forty lashes] [i haven’t been able to wear silk

since] but the part i keep forgetting.

This passage considers the essence of Sudan’s existence, assessing the significance of its fragile borders. The phrase “[sudan was always an invented country]” quotes Richard Walker’s review of James Copnall’s A Poisonous Thorn in Our Hearts: Sudan and South Sudan’s Bitter and Incomplete Divorce (2014), a text that advocates for interdependence between Sudan and South Sudan. With the inclusion of factually oriented commentary, the instability and temporality evoked by Elhillo’s metaphor of a “singed bit of paper” becomes contextualized and textually supported. In this meditation, we are met with a surge of images cloaked in Elhillo’s nostalgia, framed by the contemplation of Sudan’s political borders from an informational perspective. The phrase which follows, “[i came from a Sudan that had/gardens and magnolia flowers],” is taken from an interview with Elhillo’s mother. While the poem’s first source of found text speaks to the artificial nature of Sudan’s geographic borders, the second quotation’s source speaks to the lived realities affected by such forces. In these lines, Elhillo’s mother recounts a time when her birthplace sanctioned life, and likewise held flowers, and a time when her birthplace destroyed her brother’s body. The impression of her uncle’s fragmented body, unable to be contained in fine fabric, is the final image that closes the stanza, its last line continuing smoothly into the next poem.

The poem’s ensuing lines read:

is that i am at the jazz museum in harlem

& i am hearing the stories secondhand

& i am hearing

the stories in english on television &

i am spared the smell i am cutting

pomegranates inmy pretty kitchen

& my fingers are sweet red.

These lines narrate Elhillo’s discomfort in reconciling her geographical separation from and deep-rooted connection to the birthplace of her parents. The settings of the “jazz museum,” the “television,” and the “pretty kitchen” all represent spaces that are not war. Elhillo hears the accounts of her nation’s subjugation at the hands of British imperialism from the shelter of the not war space, counting herself as “spared.” While the first stanza defines Sudan through observation, the second epitomizes the essence of the subject on the receiving end of this information. Elhillo’s “sweet,” “red fingers” form a familiar, divergent image, antithetical to the depiction of her uncle’s maimed figure in the previous stanza.

In “vocabulary,” Elhillo demonstrates her mastery of language and its multiple meanings. Through a thought-provoking examination of the Arabic word “hawa,” which can translate as both “love” and “wind,” she invites readers to ponder the interpretation of Abdel Halim Hafez’s song “Zai al-Hawa.” The stanza finds Elhillo endeavoring to determine which meaning is referenced, as she ponders each definition:

abdelhalim said you left me holding wind in my hands

or

abdelhalim said you left me holding love in my hands

abdelhalim was left empty

or

abdelhalim was left full.

This inquiry inhabits the form of a multiple-choice exam, prompting the reader to endeavor to solve the translation’s mystery. As the words “wind” and “love” are audibly indistinguishable, Elhillo highlights the complexities of language and translation itself.

In The January Children, the power of poetry unfurls like a tapestry of emotions, weaving together the threads of nostalgia, history, and longing. With her lyrical and intricate language, Elhillo crafts a masterpiece that resonates deeply with readers, immersing them in the lens of one caught between the fractures of colonialism and the struggle for identity. She breathes life into the words on the page, inviting us to reflect on the ambiguities of language, the transience of borders, and the profound impact of cultural heritage. As the last lines of The January Children linger in our minds, we are left with an indelible imprint—a testament to Elhillo’s undeniable brilliance and her ability to captivate, transport, and inspire.

Hailing from the historic city of Philadelphia, Jada Elder is a writer and education researcher. She holds a Master of Arts degree in English from Temple University.

This post may contain affiliate links.