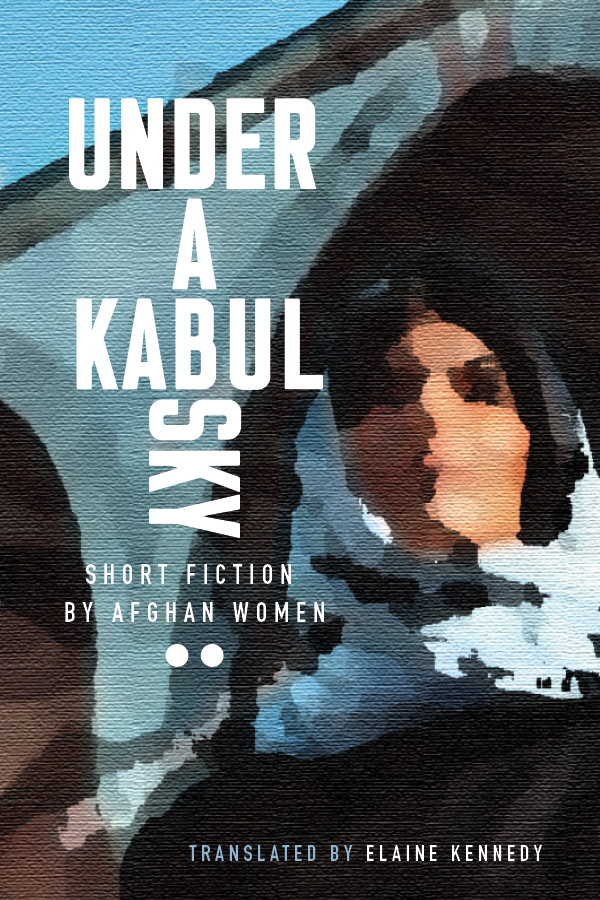

[Inanna Publications; 2022]

Tr. from the French by Elaine Kennedy; originally from the Persian by Khojesta Ebrahimi

With stories by: Wasima Badghisi, Batool Haidari, Alia Ataee, Sedighe Kazemi, Khaleda Khorsand, Masouma Kawsari, Mariam Mahboob, Toorpekai Qayum, Manizha Bakhtari, Homeira Qaderi, Parween Pazhwak, and Homayra Rafat

If there is one thing that you take away from this review, let it be that the short story genre is an exciting site of literary creativity among Afghan writers. The twelve emotionally-affecting, enjoyably strange, and formally wide-ranging works of short fiction collected in Under a Kabul Sky (translated into English by Elaine Kennedy) are testament to this fact. It is encouraging that presses like Inanna Publications are interested in publishing literary works by Afghan women, when for so long that has not been the case in the anglophone literary world.

As scholar Michelle Quay shows in her chapter “Gender and Canonization in Persian Short Story Anthologies, 1980 to 2020,” in The Routledge Handbook of Persian Literary Translation, there has been a limited presence of women authors overall in English translations of anthologies of Persian literature. But the erasure of Afghan women writers is especially shocking. Since 1980, there have been no Afghan women authors featured at all in multi-author anthologies of works translated from Persian into English. Given the cavernous absence of Afghan women short story writers in English anthologies of Persian literature, it is ground-breaking that we have collections like Under a Kabul Sky. The book spotlights an idiosyncratic group of short stories, stories that do not fall into the usual trap of essentializing Afghan women as weak people in need of (Western, military) saving.

Instead of reproducing tired stereotypes, these stories venture into the realm of the refreshingly weird. The narrative voices gathered here are by turns melodic and abrupt, jarring and inscrutable. A girl sees a man turn into a spider, a mother tosses a paper cradle into a thundering waterfall, a woman watches the night turn black as she languishes in a wolf trap, carrying on an imagined conversation with her absent brother. Each of these short fictions packs an emotional punch, and will reward attentive readers who delight in the thrill of a perfectly-executed narrative twist.

“Two Shots,” the opening story by Wasima Badghisi, holds one of the most shocking endings in the collection. The story sees a man running through a forest, trying to get back to his village. There is a blind urgency to his running; as he crosses a river bloated with dead cows and donkeys, and hears the wailing of the rising waters, the man is compelled to run faster and faster, but for a reason unknown both to himself and the reader. Upon arriving at the village, his teeth chattering with cold in the darkness, the man is confronted by a stony wall of villagers. Passing by them on the way to his mother’s house, he hears a village member mumble under his breath that he should have stayed away. “I want to get home right away,” the man thinks, “and find out what’s going on in the village.” But “what is going on in the village” proves to be a horrifying revelation to the man, one that made me shiver to read.

Another story, “Lady Khamiri, the Confidant,” by Homeira Qaderi, is similarly chilling in the revelation of its central mystery. In the story, we find the narrator, an elderly Afghan woman, puttering around her house, talking to her “confidant.” This secret-keeper, given the fanciful title of “Lady Khamiri,” is, in fact, a legless person made of bread dough, sculpted into being by the old woman herself. The starchy, silent Lady Khamiri spends each day sitting upon a dusty shelf. She has no choice but to hear the old woman’s dithering soliloquies, and to remain in place as the aging woman’s mundane ramblings turn to more sinister confessions. Lady Khamiri’s stillness and silence in the face of these horrifying admissions leaves space for the reader’s thoughts to ricochet wildly about: Is the old woman telling the truth? Is she delusional, or dangerous? If Lady Khamiri, the confidant, could speak, what would she say? At the story’s end, none of these questions are answered. As the old woman grapples to find her cane in a dimmed junk room, the reader similarly feels left—thrillingly—in the dark. And Lady Khamiri stares out, with “those wide open eyes.”

Not all of the stories are so dramatic or macabre. “Doubt,” by Khaleda Khorsand, for example, adopts the perspective of an unhappy housewife as she moves about the house. The obsessive, frantic rhythms of the woman’s thoughts—is the front door locked? Is the yogurt still fermenting in the fridge? Are the ice cubes prepared in the freezer?—are like those of a bird trapped in a cage. In a similar way, the female narrator of “The Other Side of the Window” by Homayra Rafat also relies on hyper-realist images from the more mundane aspects of her day-to-day life, such as the sound of water boiling in a kettle, the lukewarm temperature of her tea, or the falling snow outside. In “The Other Side of the Window,” this focus on small, domestic moments allows the narrator to block out the violence occurring just outside the walls of her house. Over time, however, the war outside comes to overpower the woman’s grip on the story, and her voice fades away as the narrative voice of another—a soldier—comes to dominate the text. In both Khorsand and Rafat’s short fictions, the oft-muted textures of Afghan women’s daily lives are brought to the fore, in ways that refuse sensationalization, yet which stir great feeling.

Yet, for all of the strengths of the stories in this collection, there are several missed opportunities in the book’s process of translation into English.

The stories in Under a Kabul Sky are indirectly drawn from a 2013 Persian-language anthology of short stories called Dāstān-e zanān-e Afghānistān (Stories of the Women of Afghanistan), compiled and edited by the dynamic Afghan prose writer, literary scholar, and critic Mohammad Hussain Mohammadi. In Dāstān-e zanān-e Afghānistān, Mohammadi brought together forty stories by Afghan women writers, arranging them in chronological order, from Māgah Rahmāni (b. 1945) to Narges Zamāni (b. 1998). The anthology not only features biographies and photos of each of its forty authors immediately preceding each of their selected stories, but also has a thirty-one-page introduction written by Mohammadi contextualizing the forty authors’ work within a longer history of Persian short story production in Afghanistan. Dāstān-e zanān-e Afghānistān is one of the only anthologies to be published in Persian that has seriously considered the contributions of Afghan women writers to the short story genre. It is not just a welcome text for readers of Persian short fiction, but is also a much-needed aid for scholars of Persian literature who wish to read outside of a typically masculine and Iran-centric Persian literary canon.

In 2019, the translator Khojesta Ebrahimi selected twelve stories from Mohammadi’s anthology and published them in French translation under the title Sous le Ciel de Kaboul (Under a Kabul Sky). In Ebrahimi’s slimmed-down French rewrite of Mohammadi’s anthology, however, much of his contextualizing work is cut out. The introduction, fleshed-out biographies and photos of each author, and the chronological order of Dāstān-e zanān-e Afghānistān are gone.

For better or for worse, it is Sous le Ciel de Kaboul, the much-abridged version of Mohammadi’s Dāstān-e zanān-e Afghānistān, that then served as the source text for Elaine Kennedy’s 2022 English translation of Under a Kabul Sky. The book preserves all of the unexplained cuts that Ebrahimi made in her French version of the anthology. It is relevant to underline here that Kennedy did not translate these twelve short stories from Persian, but rather worked off of Ebrahimi’s French translation. If there was an attempt to collaborate with a Persian speaker to work from Mohammadi’s Persian anthology, this is not stated in the text. Indeed, the richness of Mohammadi’s original Persian anthology is barely acknowledged in either Kennedy’s “Foreword,” or in the “Editor’s Note” in Under a Kabul Sky. It is only in small print on the copyright page that Mohammadi’s name is mentioned at all.

This seems like a missed opportunity to recognize the intellectual labor exerted by Mohammadi in his role as anthologizer in creating the source text for the French and English translations of the stories. There are dangers in inadvertently overlooking the work of others (especially those working outside of English, in marginalized languages like Persian) in the translation process, as seems to have happened in the case of Under a Kabul Sky. I point this out here in the hope that, in the future, such oversights do not become habits in the translation of Persian texts into English.

Future translators and publishers may do well to engage with organizations, individual translators, and even a forthcoming translation prize that are all aimed at engaging with Persian literature in English translation, including and beyond Under a Kabul Sky. These include Poetry Translation Center (Farsi), and translators: Michelle Quay, Amy Motlagh, Poupeh Missaghi, Mariam Rahmani, Sara Khalili, Salar Abdoh, M.R. Ghanoonparvar, Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi, Patricia Higgins, and others. Also worth noting is the Mo Habib Translation Prize in Persian Literature, which announced its inaugural winner for Persian fiction translated into English in June 2023.

But, as I mentioned at the beginning of this piece: If there is one thing that I hope you take away from this review, it should be that the short story genre is an exciting site of literary creativity among Afghan writers. The stories in Under a Kabul Sky are, as Kennedy herself writes in her Foreword, “upside-down worlds,” in which “a river can wail, turn into a flood and wash nature, human and beast away.” These are compelling narratives, ones that not only unsettle flattened representations of Afghan women, but also shake up the short story genre in English.

(My immense thanks to Dr. Aria Fani, Shoaib Laghari, Cara Reed, and Scott Learn for their help in thinking through this review.)

Anna Learn is a PhD student at the University of Washington, where she studies Persian, South Asian, and Hispanic literature.

This post may contain affiliate links.